Created in partnership with the Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights

Occupational Safety and Health

Each day, 7,500 people die from unsafe and unhealthy working conditions and many others develop long-term physical and mental health issues.Overview

What is Occupational Safety and Health?

Safety and health in the workplace — otherwise known as occupational safety and health (OSH) — is improvement of working conditions and environments to ensure workers’ safety and health are maintained while working and to provide compensation if a work-related injury occurs.

OSH is regulated at international, regional and national levels. Safety and health in the workplace do not just apply to typically dangerous jobs, such as working at height or with chemicals, but to all places of employment, including offices. OSH laws and regulations also include the requirement of employers to adapt work and the workplace to the capabilities of workers in light of their physical and mental health.

OSH is considered an integral part of the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health (or to put it simply “the right to health”), which is affirmed in the UDHR, the ICESCR and many other international human rights instruments. Moreover, healthy and safe occupational conditions are considered one of the key underlying determinants of health: i.e. a precondition for the effective enjoyment of the right to health.

What is the Dilemma?

The dilemma for responsible business is how to ensure that workplaces are safe for all workers, in all locations of their business or supply chain, particularly when operating in countries in which national safety and health and employment injury protection schemes are deficient, or where there is an absence of a culture of safety and health at the national and workplace levels.

Responsible businesses can find themselves in situations where their own safety and health requirements and standards cannot be met by suppliers or business partners due to a lack of equipment or resources in their country, or an unwillingness to put standards in place beyond local legal compliance that may be seen as an unnecessary expense. Additionally, adapting the workplace or work activities to meet individual worker needs can be challenging as different workers will have different requirements.

Prevalence of Occupational Safety and Health Problems

The ILO estimates that 2.78 million workers die each year from occupational accidents and work-related diseases, and an additional 374 million workers suffer from non-fatal occupational accidents. This corresponds to 7,500 deaths from unsafe and unhealthy working conditions every single day, 6,500 of which can be attributed to work-related diseases and 1,000 to occupational accidents. This is an estimation as many workplace deaths or injuries are not reported to relevant authorities. Additionally, long-term work-related illness or death (such as respiratory disease or cancers suspected to be caused by working with chemicals) may also go unreported as the illness or death may occur many years after employment ends.

Many employees also experience mental health problems such as anxiety or stress that can be exacerbated or caused by work and work environments, and can also lead to long-term sickness or days off work due to mental ill-health. World Health Organization (WHO) studies suggest that there is a cost of over US$1trillion to the global economy each year from lost productivity due to mental health problems.

Key trends include:

- The burden of occupational mortality and morbidity is not equally distributed across the world, among industries, and among the workforce. About two-thirds (65%) of global work-related mortality is estimated to occur in Asia, followed by Africa (11.8%), Europe (11.7%), America (10.9%) and Oceania (0.6%). The rates of fatal occupational accidents per 100,000 workers also show stark regional differences, with those in Africa and Asia between 4 and 5 times higher than those in Europe.

- Manufacturing, construction, transportation and storage are the industries that experience the highest level of work-related accidents. In these highly hazardous sectors, as well as elsewhere, work-related injuries are not equally distributed among the workforce. The workers most exposed to work-related injuries are those in precarious employment (temporary, casual or part-time workers), workers in informal employment, those working in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and those subject to discrimination and marginalization (such as migrant workers, young workers, and racial and ethnic minorities).

- The world was profoundly affected by the global pandemic. Due to COVID-19 risks, business had to adapt to restrictions set by Governments around the world to keep their workforces safe, including allowing workers to ‘work from home’ where possible, creating shift patterns to allow for social distancing and introducing heightened cleaning and sanitation protocols to keep employees safe. As the world recovers from COVID-19, these practices continue, with many industries, such as professional services, changing their working styles to more flexible, hybrid working approaches. These have created new challenges for OSH, including ensuring workers have appropriate equipment to use at home to complete their jobs. There has also been a rise in mental health concerns as workers feel more isolated and are unable to clearly separate work and home life.

- Mental health accommodation and protection in the workplace have become increasingly common in OSH planning and management. Mental health issues, such as work-related stress or depression, not only affect the individual but also result in lost business productivity. While in some countries mental health issues are still seen as taboo or controversial, many businesses are proactively supporting mental health and well-being approaches for employees.

- The World Bank estimates that around 1 billion people — 15% of the global population — experience some form of disability. As such, OSH management is developing to increasingly accommodate physical disabilities, such as blindness or physical restrictions, as well as mental disabilities, such as autism, dyslexia or learning disabilities. The ILO highlights that businesses that are inclusive of disabilities in the workplace are more likely to have positive workforce morale, high levels of productivity and a more diverse workforce.

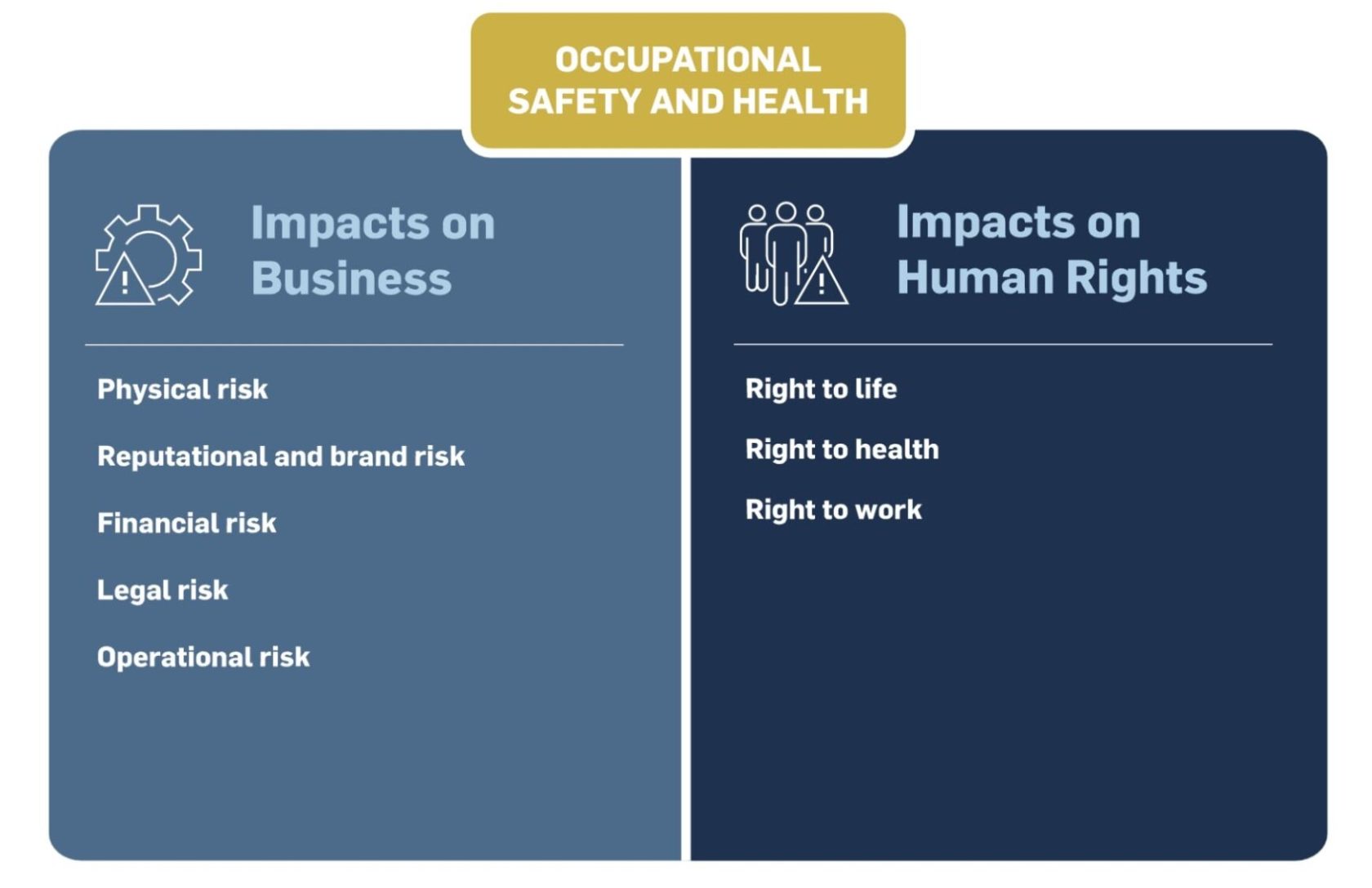

Impacts on Businesses

While OSH hazards are intrinsic to all workplaces, those located in countries with limited resources, weak legal frameworks, inadequate enforcement and support functions face greater challenges. This is often exacerbated by the absence of a preventive safety and health culture, both at national and workplace levels, and the lack of protection schemes against work-related injury. Businesses can be impacted by OSH issues in their operations and supply chains in multiple ways:

- Physical risk: Safety and health accidents can include major incidents like fires, explosions or building collapses that not only hurt employees but also destroy and damage property, costing companies considerably to rebuild.

- Reputational and brand risk: Negative campaigns by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), trade unions, consumers and other stakeholders can result in reduced sales and/or brand erosion.

- Financial risk: Divestment and/or avoidance by investors and finance providers (many of which are increasingly applying environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria to their decision-making) can result in reduced or more expensive access to capital and reduced shareholder value.

- Legal risk: Legal claims can be brought against the company, and it may face criminal charges when workers are hurt or killed.

- Operational risk: OSH incidents and associated media coverage and/or boycotts may lead to higher costs and/or disruption of business continuity. Companies may respond by terminating supplier contracts and/or directing sourcing activities to lower-risk countries.

Impacts on Human Rights

Poor occupational safety and health has the potential to impact a range of human rights[1], including but not limited to:

- Right to life and physical security (UDHR, Article 3): This article of the Universal Declaration affirms the right to life, liberty and security of the person. Poor OSH practices can affect workers’ physical security and, in the worst cases, affect the fundamental right to life.

- Right to health (UDHR, Article 25, ICESCR, Article 12): These provisions guarantee the right of everyone to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, which is explicitly connected to the improvement of “industrial hygiene” and the prevention and treatment of occupational diseases. The right to health can be compromised by an unhealthy or dangerous working environment. Both one-off accidents or long-term working conditions can affect a person’s health and well-being, including mental health.

- Right to work (UDHR, Article 23; ICESCR, Article 7): The entitlement of everyone to safe and healthy working conditions is also considered an integral part of the right to work, which encompasses also the right to enjoy just and favourable conditions of work. This requires putting in place preventive measures in respect of occupational accidents and diseases.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The following SDG targets relate to safety and health:

- Goal 3 (“Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages”), Target 3.9: By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water, and soil pollution and contamination.

- Goal 8 (“Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all”), Target 8.8: Protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments of all workers, including migrant workers, particularly women migrants, and those in precarious employment.

- Goal 16 (“Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels”), Target 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels.

Key Resources

The following resources provide further information on how businesses can address occupational safety and health risks in their operations and supply chains:

- ILO and United Nations Global Compact, Nine Business Practices for Improving Safety and Health Through Supply Chains and Building a Culture of Prevention and Protection: This report identifies practices that businesses can implement to advance decent work and improve occupational safety and health globally, especially when operating in countries with deficient national safety and health and employment injury protection schemes.

- ILO, Occupational Safety and Health in Global Value Chains Starterkit: This tool provides guidance on how to map drivers and constraints for OSH improvements integrating safety and health approaches throughout the value chain, and provides case studies on the agriculture and garment industry.

- ISO, 45001: Occupational Health and Safety Standard: The first international standard on safety and health, which builds on OHSAS18001 and is structured in a similar way as other ISO management systems (such as ISO 14001 or ISO 9001).

- The Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH), Delivering a Sustainable Future: This report maps the key elements of OSH management with the SDG targets.

Definition & Legal Instruments

Definition

According to the ILO, safety and health in the workplace is defined as “the discipline dealing with the prevention of work-related injuries and diseases, as well as the protection and promotion of the health of workers”[1], where health “encompasses the social, mental and physical well-being of workers”.

The WHO has summarized the various definitions of occupational safety and health and characterizes OSH practice as activities that:

- Protect and promote the health of workers by preventing and controlling diseases and accidents and by eliminating occupational factors and conditions hazardous to safety and health at work;

- Develop and promote healthy and safe work, work environments and work organizations;

- Enhance the physical, mental and social well-being of workers and supports the maintenance and development of working capacity, as well as professional and social development at work; and

- Enable workers to conduct socially and economically productive lives, while contributing positively to sustainable development.

Occupational safety and health is an integral part of individuals having ‘decent work’, which is defined by the ILO as the “right to productive work in conditions of freedom, equity, security and human dignity”. The ILO states that work can “only be decent if it is safe and healthy”. OSH programmes should therefore provide safe and healthy working conditions for all workers, which includes making special arrangements or provisions for employees with additional needs due to disability or other personal circumstance, such as pregnancy or mental illness. However, there is no zero-risk working environment. That is why OSH should also cover the protection, in the form of compensation and access to medical care, available to workers or their families in the case of an occupational accident or disease.

Sources of Occupational Injuries

- Accidents: Accidents can vary depending on the workplace and the nature of the incident. However, common accidents in the workplace can include slips, trips and falls, cuts and lacerations, vehicle accidents and collisions, and burns.

- Exposure to hazards and hazardous substances: Exposure to hazards can cause a one-off incident (for instance a fall from height), or longer-term issues, such as respiratory disease from inhaling hazardous chemicals over a period of time. Some of the most common hazards include exposure to chemicals, metal elements, dust, silica, loud noise, bright light and gases. Hazardous substances are usually defined in law in the country of operation, but international guidance on the recognition of occupational diseases due to exposure to hazardous substances also exists and is provided by ILO.

- Musculoskeletal disorders and repetitive strain injuries: These injuries occur from manual handling of objects at work. This can range from lifting heavy loads to sitting at a computer for long periods of time. Repetitive motions can also cause long-term injuries such as damage to nerves, joints and muscles if not managed correctly.

- Communicable diseases: Workers risk contracting communicable diseases due to working conditions, such as outdoor work or relocation for employment. Some of the most common and burdensome communicable diseases include malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS and — since 2019 — COVID-19. There may be other incidences of localized communicable diseases, such as stomach viruses or flu, where workers are close together or share equipment and spaces.

- Mental ill-health: Mental conditions can stem from many causes, but several workplace factors may contribute to or trigger these conditions. Stress and anxiety can result from workplace situations such as excessive working hours, unsafe conditions or bullying in the workplace.

Legal Instruments

ILO Conventions

In June 2022, the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work(1998) was amended to include “a safe and healthy working environment” as a fundamental principle and right at work. Consequential amendments were also made to the ILO Declaration on Social Justice for a Fair Globalization (2008) and the Global Jobs Pact (2009) to reflect this.

The two core ILO conventions that describe the core principles and rights in the field of OSH and serve as the basis for the more advanced safety and health measures described in other OSH instruments are:

- ILO Convention on Occupational Safety and Health, No. 155 (1981)

- ILO Promotional Framework for Occupational Health and Safety Convention (No. 187)(2006)

All Members, even if they have not ratified these two conventions, now have an obligation arising from the very fact of membership in the ILO to respect, to promote and to realize, in good faith and in accordance with the ILO Constitution, the principles concerning the fundamental right to a safe and healthy working environment.

Additionally, the ILO has adopted more than 40 standards specifically dealing with occupational safety and health, as well as over 40 Codes of Practice that address OSH across a range of industries. Other key instruments on occupational safety and health include the following:

- ILO Convention on Occupational Health Services, No. 161(1985)

- ILO Recommendation on Occupational Safety and Health, No. 164(1981)

Businesses can look to conventions relevant to their industry for guidance on what countries that ratified these conventions should be implementing, and what would be expected of businesses. Businesses can also consult ILO Codes of Practice specific to different industries, for example:

Other Relevant ILO Conventions on Safety and Health

ILO conventions on safety and health in particular branches of economic activity include the following:

- ILO Convention on Safety and Health in Agriculture, No. 184 (2001)

- ILO Convention on Safety and Health in Mines, No. 176 (1995)

- ILO Convention on Safety and Health in Construction, No.167 (1988)

- ILO Convention on Hygiene (Commerce and Offices), No.120 (1964)

There are also standards and conventions that address particular working situations, such as how to deal with harmful chemicals or accidents. Key ones include:

- ILO Convention on Prevention of Major Industrial Accidents No. 174 (1993)

- ILO Convention on Chemicals, No. 170 (1990)

- ILO Convention on Radiation Protection, No. 115 (1960)

- ILO Convention on Asbestos, No. 162 (1986)

Complementing the above conventions, the ILO has also adopted specific instruments on the protection that workers should benefit against work-related injury:

- ILO Convention on Social Security (Minimum Standards), No. 102, Part VI (1952)

- ILO Convention on Employment Injury Benefits, No. 121 (1964, amended in 1980)

Other Legal Instruments

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) set the global standard regarding the responsibility of business to respect human rights in their operations and across their value chains. The Guiding Principles call upon States to consider a smart mix of measures — national and international, mandatory and voluntary — to foster business respect for human rights.

Regional and Domestic Legislation

OSH laws differ around the world, with different nations implementing and enforcing their own laws. There are also regional laws and regulations to consider, such as European Union directives on safety and health at work. OSH requirements also differ dramatically between different industries and employment types depending on the risks that the workers face and the activities undertaken. Businesses should check the safety and health laws in their countries of operation and require that suppliers adhere to all safety and health laws in their own countries of operation. For detailed information on country legislation, businesses can refer to ILO’s LEGOSH and NORMLEX database, which provides information on country ratifications of ILO conventions and links to national legislation.Companies are increasingly subject to non-financial reporting requirements and due diligence obligations in the jurisdictions in which they operate, which often include disclosures on their performance. There are several high-profile examples of national legislation that specifically mandate human rights-related reporting and other positive legal duties, such as due diligence, including the United Kingdom Modern Slavery Act 2015, Australian Modern Slavery Act 2018, the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act 2010, the French Corporate Duty of Vigilance Law 2017, the German Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains 2023 and the Norwegian Transparency Act 2022.

Also, in 2021 the Netherlands submitted a Bill for Responsible and Sustainable International Business Conduct, and the European Commission announced its Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). This Directive is likely to come into force between 2025 and 2027 and will make human rights and environmental due diligence mandatory for larger companies.

These mandatory due diligence and disclosure laws require companies to publicly communicate their efforts to address actual and potential human rights impacts, including health and safety violations. Failure to comply with these obligations leads to real legal risk for companies.

Contextual Risk Factors

The prevention of inadequate safety and health in the workplace requires an understanding of its underlying causes and the considerations of a wide range of issues that often interfere and reinforce one another.

Key risk factors include:

- Weak national occupational safety and health systems, lack of Government capacity to develop and implement OSH policies and programmes, or underdeveloped OSH qualification frameworks that lead to a scarcity of OSH specialists and services.

- Poor regulatory framework that may not adequately cover all sectors, groups of workers, or occupational hazards.

- Poorly enforced domestic laws can result in inadequate operations of labour inspectorates, poorly planned inspections and insufficient training of labour inspectors, as well as potential corruption.

- Prevailing work culture may not prioritize the value of prevention. If hazardous activities and substances are not properly labelled or explained, workers may not know the risks they face.

- Shortage of decent work can lead workers to accept roles or undertake dangerous or harmful work out of desperation for work.

- High proportion of workers in the informal economy can make it difficult to trace supply chains and present significant challenges for businesses implementing OSH processes. Additionally, informal workers may not be reporting OSH risks or issues for fear of losing work.

- Discrimination or cultural stigma may lead workers to hide disabilities from employers or prevent employers from making adequate protections for affected persons, for instance not hiring people with physical disabilities.

Industry-specific Risk Factors

Safety and health risks exist in all industries and sectors. Every worker has the right to health, and hazards to health exist for all people in everyday life, including in the workplace. Industries that may not seem particularly hazardous — for instance office work — can still present OSH risks, such as trips and falls over office equipment, back pain from sitting at a computer or fire safety in buildings. The ILO has a helpful encyclopedia on OSH, available here.

The following industries present particularly high levels of risk. To identify potential OSH risks for other industries, companies can access the CSR Risk Check.

Agriculture

According to the ILO, agriculture with over 1.3billion workers worldwide is one of the three most dangerous industries (alongside construction and mining). Safety and health risks are higher for informal/undocumented workers than for formally employed workers, as they are less likely to have safety and health protections in place.

Agriculture-specific risk factors include the following:

- Physical and manual labour: Many agricultural jobs require physical and manual labour, often outdoors. This presents immediate physical risks to the safety and health of workers, as without proper training or protection workers could become ill from exposure to the elements, exhaustion or repetitive physical movement or overexertion.

- Harmful chemicals: Agricultural jobs often involve chemicals which can be harmful to workers, especially if protective equipment is not provided. Fertilizers and pesticides can cause respiratory diseases, and some can be fatally poisonous if ingested.

- Women: Women are particularly at risk from working with chemicals and pesticides, as many of these chemicals can affect fertility or have harmful impacts on fetuses in pregnant women. Female agricultural workers are also vulnerable to sexual harassment and violence.

- Equipment and machinery: Many roles in the agriculture industry require machinery or equipment, such as chainsaws in forestry, machetes in manual sugar cane harvesting or tractors in pastoral farming. These machines can cause accidents and injuries without proper selection of safe equipment, training, maintenance and protective equipment.

- Seasonal work: Agricultural work is often seasonal, and many workers will be paid based on their output as opposed to a set wage. This can cause workers to undertake long hours and overexert themselves (for instance carrying heavy weights) to achieve the best payments. This can not only cause physical risks to safety and health but also mental ill-health through stress and exhaustion.

- Proximity to other workers: Seasonal and migrant work can also exacerbate the risks of communicable diseases spreading, as workers can live and work in close contact. Reports show that temporary migrant worker accommodation was a ‘hot spot’ for COVID-19 transmission during the global pandemic. This can also apply to other communicable diseases such as tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS.

- Remoteness: A lot of agricultural work is done in remote locations where safety and health protections may be hard to implement. Some businesses may also take advantage of the remote locations and not provide proper safety and health protections, as labour inspectors are unlikely to check remote sites.

- Child labour: Children under the age of employment may be engaged in agricultural undertakings, where they may be involved in hazardous occupations. According to the latest ILO estimates, the prevalence of child labour in rural areas is about three times higher than in urban settings. For many young children, agriculture often serves as an entry point to the labour market.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Occupational Safety and Health in Agriculture, on Plantations, and in Other Rural Sectors: A compilation of resources by the ILO on OSH in agriculture.

- OECD-FAO, Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains: This guidance provides a common framework and globally applicable benchmark to help agri-businesses address negative impacts, such as OSH accidents and incidents. The guidance is relevant for enterprises across the entire agricultural supply chain, from the farm to the consumer.

- ILO, Safety and Health in Agriculture: This code of practice provides guidance on how to implement safety and health practices in the agriculture industry and supply chains, including emergency preparedness and protective equipment.

- ILO, Food and Agriculture Global Value Chains: Drivers and Constraints for Occupational Safety and Health Improvement: Comprehensive guidance on OSH issues for agricultural value chains in two volumes (Volume 1, Volume 2 and Executive Summary).

- ILO, Ergonomic Checkpoints in Agriculture: Practical and Easy-to-Implement Solutions for Improving Safety, Health and Working Conditions: Tangible and practical steps for OSH improvement in agricultural workplaces.

- Fairtrade International, Guide for Smallholder Farmer Organisations – Implementing Human Rights and Environmental Due Diligence (HREDD): This guidance was developed to provide advice and tools on HREDD for farmer organisations to implement.

Construction

The construction industry poses many risks to workers’ safety and health, and is another of the top three most hazardous industries according to the ILO. Even in countries where safety and health regulations are well enforced and adequate approaches are taken by companies, accidents can still happen. In countries where there is a lower commitment of companies and weak enforcement of safety and health rules, construction environments can be deadly. Since construction is an activity that is directly or indirectly relevant to all sectors, it is important for businesses to consider construction-related safety and health risk exposures across their value chain.

Construction industry specific risk factors include the following:

- Methods of work: Working at height, in trenches or with heavy machinery can be dangerous, particularly if risks are not adequately assessed, if engineering and administrative controls are not in place, if personal protective equipment is not provided free of charge to workers, if activities of different subcontractors are not coordinated, and if inadequate training has been given to workers on how to do their jobs safely.

- Materials: Many of the materials used in construction can also be dangerous, such as heavy stones or steel, and can cause injury or death if these fall or trap workers.

- Poor safe and health on sites: In countries where employers do not ensure construction sites under their control are safe and healthy, as reasonably as possible, and where safety and health regulations are not well enforced, many construction workers can find themselves exposed to uncontrolled risks, or without PPE or other safety equipment, leaving them vulnerable to injuries and accidents. Inadequate living conditions for workers of major construction projects, many of whom are migrant workers, increase the risk of transmission of communicable diseases.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Occupational Safety and Health in the Construction Sector: A compilation of resources from the ILO on OSH conventions, programmes and guidance for the construction sector.

- ILO, Good Practices and Challenges in Promoting Decent Work in Construction and Infrastructure Projects: This paper provides key information on issues impacting the construction industry, including occupational safety and health, and examples of good practices.

- ILO, The Health of Workers in Selected Sectors of the Urban Economy: Challenges and Perspectives: This paper is aimed at analyzing and systematizing the health challenges faced by the poorest strata of urban workers in the following sectors: construction, waste picking and recycling, street trading, domestic work and agriculture.

- ILO, Safety and Health in the Construction Sector: Overcoming the Challenges: A webinar with ILO experts dealing with occupational safety and health and the construction sector to discuss the challenges of protecting workers. The webinar aims to provide practical guidance to enterprises wishing to make safety and health an integral part of their business model. The webinar recording is available here.

- ILO, The Role of Worker Representation and Consultation in Managing Health and Safety in the Construction Industry: This paper contributes to the discussion on the importance of workers’ participation and representation for the improvement of safety and health conditions in construction, firstly by presenting a set of definitions, followed by evidence of the effectiveness of worker representation and consultation in safety and health generally and in the construction sector in particular.

- Building Responsibly, Worker Welfare Principles: These Principles were developed to serve as the global standard on worker welfare for the engineering and construction industry. Principle 5 provides guidance on key challenges for OSH and components for consideration to improve safety standards.

Mining

The mining industry is the third most dangerous industry for workers according to the ILO. Mining poses a range of OSH risks to workers, as well as to communities surrounding mining and refining sites. Immediate physical dangers to workers in mines are compounded by long-term disease and sickness that can develop due to mining conditions over time. Small scale mining is often informal, and conditions are “far from conforming with international and national labour standards”, according to the ILO. It is estimated that small scale mining accident rates are six to seven times higher than large scale mining operations, even in developed countries. There have been many notable mining disasters in developed and developing countries over the last 20 years, including the Brumadinho dam collapse (Brazil), the Sago mine explosion (USA) and the Ulyanovskaya mine explosion (Russia), in addition to regularly reported smaller incidents of deaths in mines.

Mining-specific risk factors include the following:

- Underground mines: Working underground in confined spaces, which are often dark and have limited ways of evacuating or escaping, is inherently dangerous. Moving and working in extremely low spaces poses a risk to the workers’ body posture and can lead to physical pain and shorter life spans. The risk is compounded by the likelihood of gases and chemicals being found underground that can ignite causing explosions and fires.

- Heavy machinery: Working with heavy machinery, including industrial diggers and trucks, large drills, rock crushers and even explosives can lead to risks of being caught in or crushed by machinery. The vibration from machinery can result in musculoskeletal disorders and even paralysis if the vibration or ‘shock’ is significant enough. Where safety and health is not planned, safe equipment is not selected or properly maintained, operations are not coordinated, and workers are not properly trained or not provided adequate PPE, the risk of accidents or even death grows exponentially.

- Air pollution: Dust and particles released from mining can cause long-term respiratory diseases if they are inhaled by workers. Common respiratory diseases from mining include bronchitis, silicosis and pneumoconiosis.

- Loud noises: Exposure to loud noises, such as mining machinery, falling rocks and explosions, can result in hearing disorders for workers, including hearing impairment, hearing loss and conditions like tinnitus.

- Waste storage: Effluents and waste from mining is often stored in pond-like structures called tailings. These can become poisonous and toxic, can poison nearby soil or waterways through a process called ‘seepage’, and can in some cases become flammable, presenting a fire risk. Tailingscan ‘leak’, causing the effluent to escape leading to damage to nearby land and communities, sometimes to catastrophic effect, such as in the Vale dam

- Diseases: Mining activities are often located in or near places with highly prevalent communicable diseases — such as tuberculosis and malaria. In addition, as mining is still a male dominated industry and particularly when mines are in impoverished areas, workers paying for sex is common. This can lead to a risk of HIV/AIDSin workers, and the surrounding communities.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Occupational Safety and Health in the Mining Sector: A compilation of resources from the ILO on OSH conventions, programmes and guidance for the mining sector.

- ILO, Code of Practice on Safety and Health in Opencast Mines: ILO code includes guidance on risk assessment and management, as well as setting up OSH management systems and emergency response in opencast mines. The code also comprises descriptions of specific hazards and describes respective control measures.

- ILO, Safety and Health in Underground Coal Mines: ILO code provides a methodology for identifying hazards and addressing OSH risks in underground mines, ranging from dust, explosions, fires and water inflows to electrical hazards, machinery and hazards on the surface.

- ILO, HIV and AIDS: Guidelines for the Mining Sector: A collection of specific guidance on HIV and AIDS from the ILO that aims to support companies in the mining sector in strengthening their response to HIV and AIDS.

- ICMM, Good Practice Guidance on Occupational Health Risk Assessment: In-depth guidance and steps on conducting an OSH risk assessment in mining and metals processing.

- ICMM, Community Health Programs in the Mining and Metals Industry: Analysis of community health initiatives undertaken by ICMM member companies and an overview of key lessons learned.

- ICMM, Leadership Matters: The Elimination of Fatalities: A guide for senior leaders to prevent fatalities in the mining sector through their personal actions and the processes and activities they should ensure are in place.

- ICMM, Leadership Matters: Managing Fatal Risk Guidance: This guidance provides a tool for senior managers to help reduce fatalities in the mining sector and includes a series of self-diagnostic prompts to assist in identifying gaps in safety management systems.

- ICMM, Health and Safety Performance Indicators: A detailed report on OSH performance indicators (i.e. injury and disease recording) for mining companies.

Oil and Gas

The oil and gas industry can be dangerous for workers. Both onshore and offshore work requires a high level of skill and strict safety and health measures to keep workers safe. Extensive research has been done on the dangers of working with oil, gas and related substances, both in day-to-day work activities and the long-term health implications of exposure to substances.

Oil and gas-specific risk factors include the following:

- Extraction sites: The construction, maintenance and installation of oil and gas extraction sites (for instance oil rigs at sea) is dangerous due to the machinery used, and the hazards that working at sea can cause. Once constructed, there are significant risks to workers such as falling from heights, drowning and hypothermia.

- Flammable products: Oil and gas products are usually highly flammable, which makes the risk of explosions and fires high. This can destroy facilities, cause burns, respiratory problems or even death, and can have devastating effects on the local environment and communities.

- Mental illness: Mental illness is also a risk for those working in the oil and gas industry, as a lot of workers are required to work away from home for long periods of time and in high pressure roles. Depression, anxiety and stress-related illnesses can be common in these environments.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Occupational Safety and Health in the Oil and Gas Production and Refining Sector: A compilation of OSH resources by the ILO for oil and gas companies.

- International Association of Oil & Gas Producers: The association has a range of guidance and tools for oil and gas companies, including how to implement safety and health practices for offshore work, transportation of dangerous chemicals and geophysical operations.

- IPIECA: The industry-wide sustainability membership body has a range of resources and tools on safety and health approaches, risk assessments and OSH specialist working groups.

Fashion and Apparel

The fashion and apparel industry has a range of safety and health issues for businesses to consider. As well as direct risks to workers in their day-to-day activities — such as using sewing machinery or chemical dyes — industry-wide issues with the safety of textile factories and excessive working hours have been identified in the manufacturing stages in developing countries. The risks found in the agricultural sector apply to workers sourcing raw materials (such as rearing cattle for leather or picking cotton) in the fashion and apparel industry. Women represent an average of 68% of the garment workforce and 45% of the textile sector workforce, which means that OSH issues and incidents in this sector affect mostly women.

Fashion and apparel specific risk factors include the following:

- Subcontracting: This industry features a lot of subcontracting and outsourcing, making tracing where a product was made and under what conditions difficult. A lot of garment workers are also employed, formally and informally, in homeworking with limited OSH protections and PPE, which makes preventing and recording OSH issues difficult.

- Dangerous activities: Certain activities specific to this industry can be dangerous to health, such as the process of sandblasted denim and using certain dyes to change the colour of textiles. Some brands, such as ASOS, now prohibit or are phasing out these activities due to their dangerous nature.

- Cost vs profit: The increasingly low cost of fashion and apparel items means that factories and manufacturers in the supply chain must reduce their own costs to make profit. This can include cutting corners with safety and health, such as working in unsafe buildings or failing to provide PPE for workers. The Rana Plaza disaster of 2013 is an example of unsafe working conditions leading to the deaths of 1,132 people.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Occupational Safety and Health in the Textiles, Clothing, Leather and Footwear Sector: A compilation of resources from the ILO on OSH conventions, programmes and guidance for the textile and apparel sector.

- OECD, Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains in the Garment & Footwear Sector: This guidance aims to help fashion and apparel businesses implement the due diligence recommendations contained in the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises in order to avoid and address the potential negative impacts of their activities and supply chains on a range of human rights, including safety and health.

- SOMO, Fatal Fashion: Analysis of Recent Factory Fires in Pakistan and Bangladesh: A Call to Protect and Respect Garment Workers’ Lives: This report describes two factory fires ravaging the facilities of clothing manufacturers in Pakistan and Bangladesh in September 2012 and leading to hundreds of workers being killed and injured. The report demonstrates the urgent need for immediate and structural changes in the practices of Government and business actors in the global garment industry.

- Clean Clothes Campaign: Provides a tracker on key safety and health related events in the garment industry.

Due Diligence Considerations

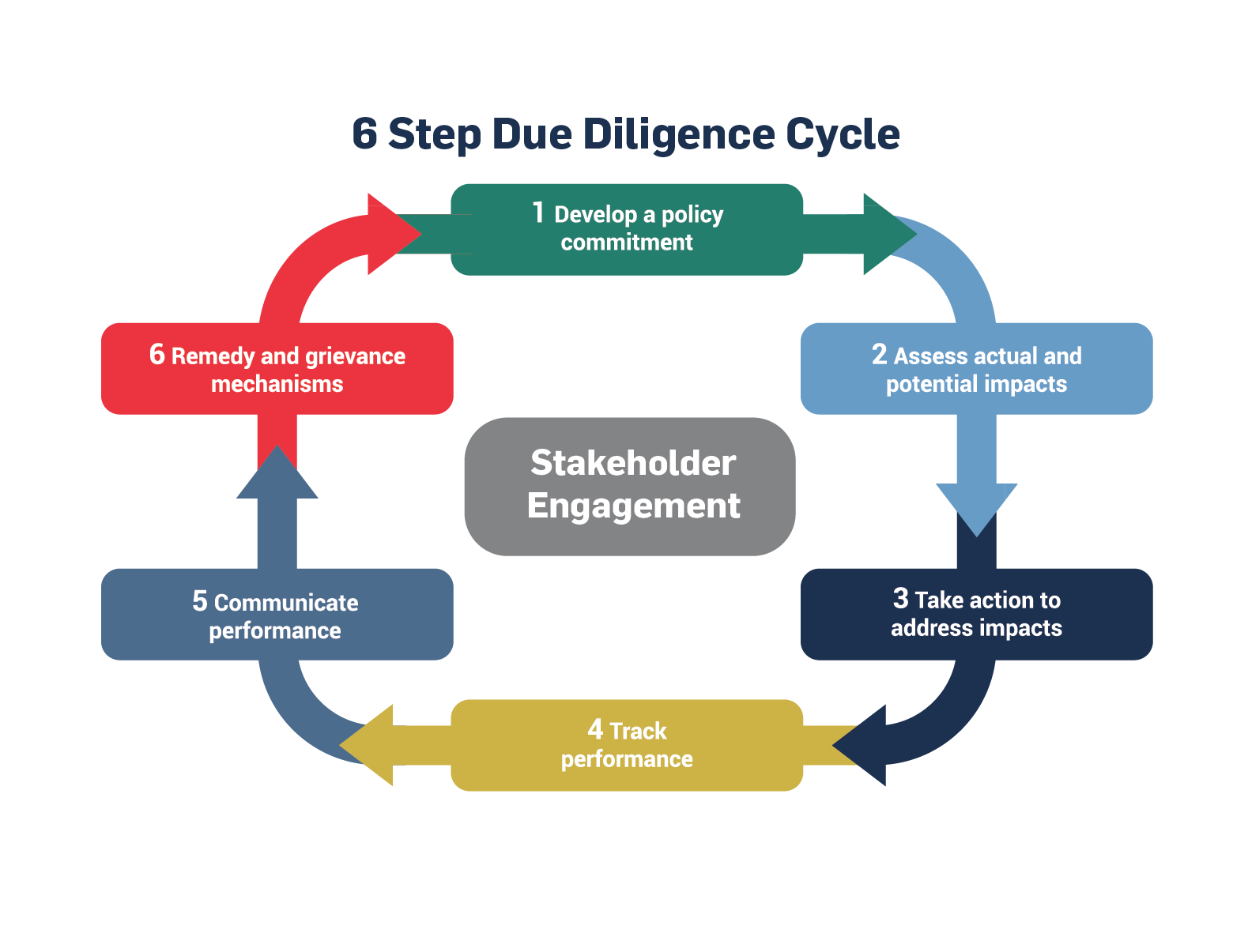

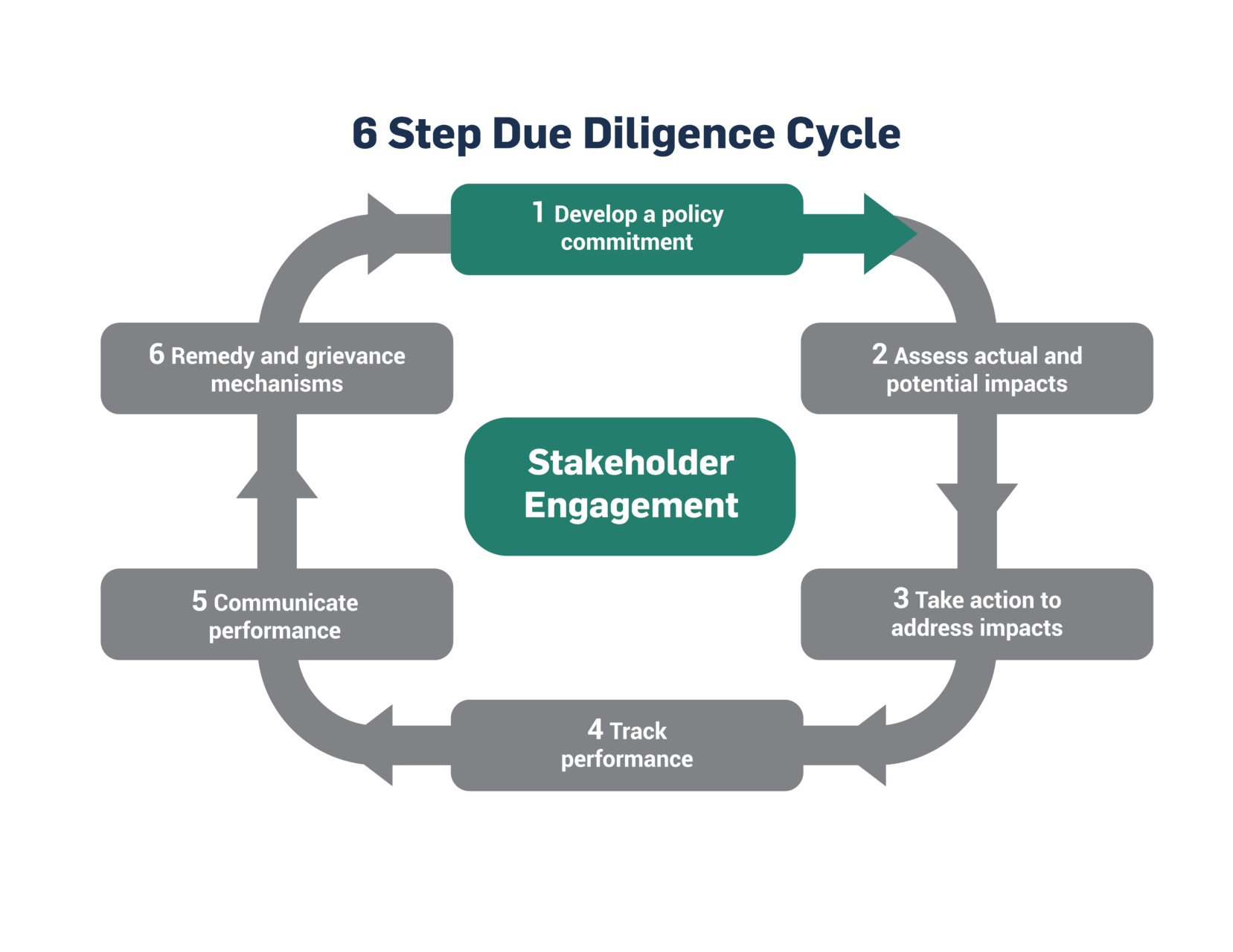

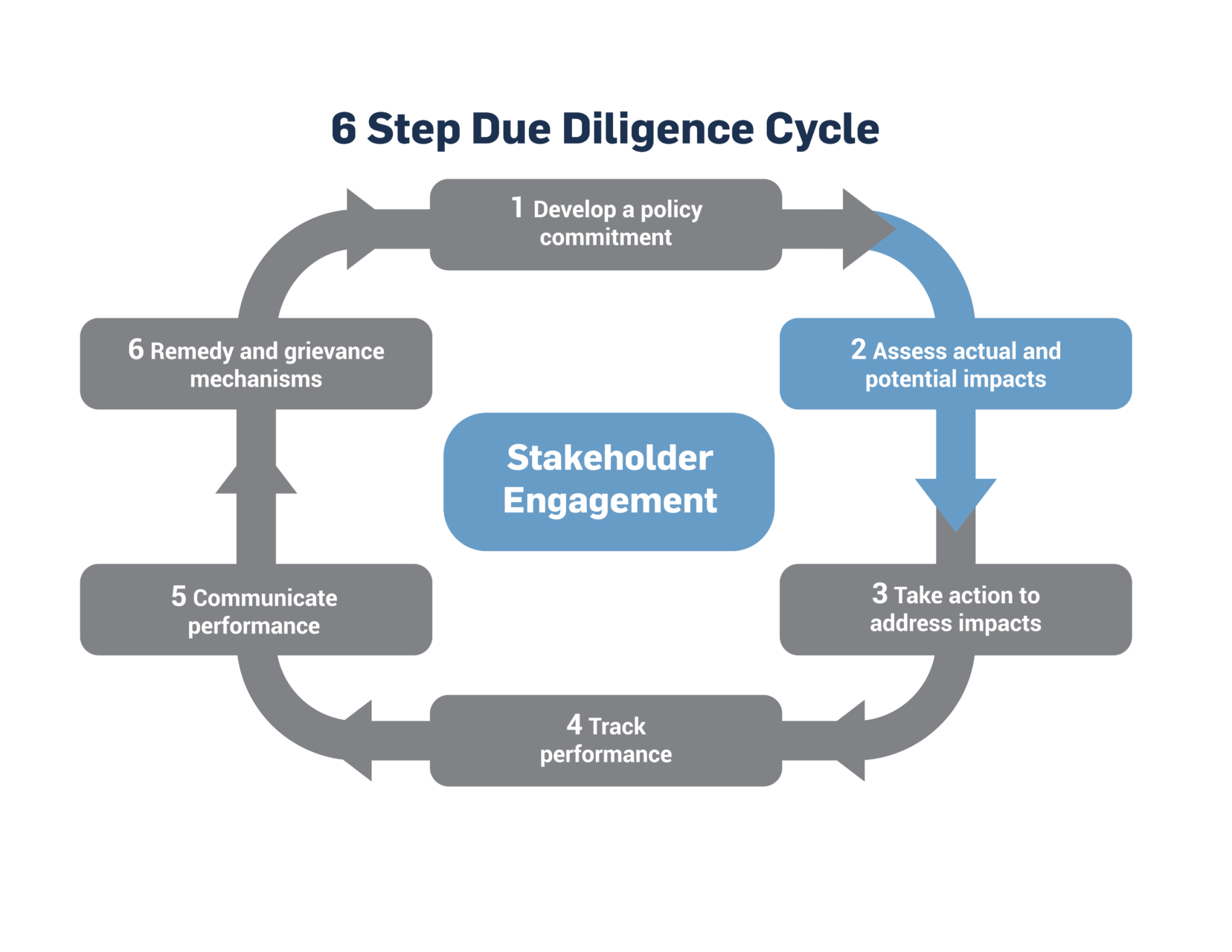

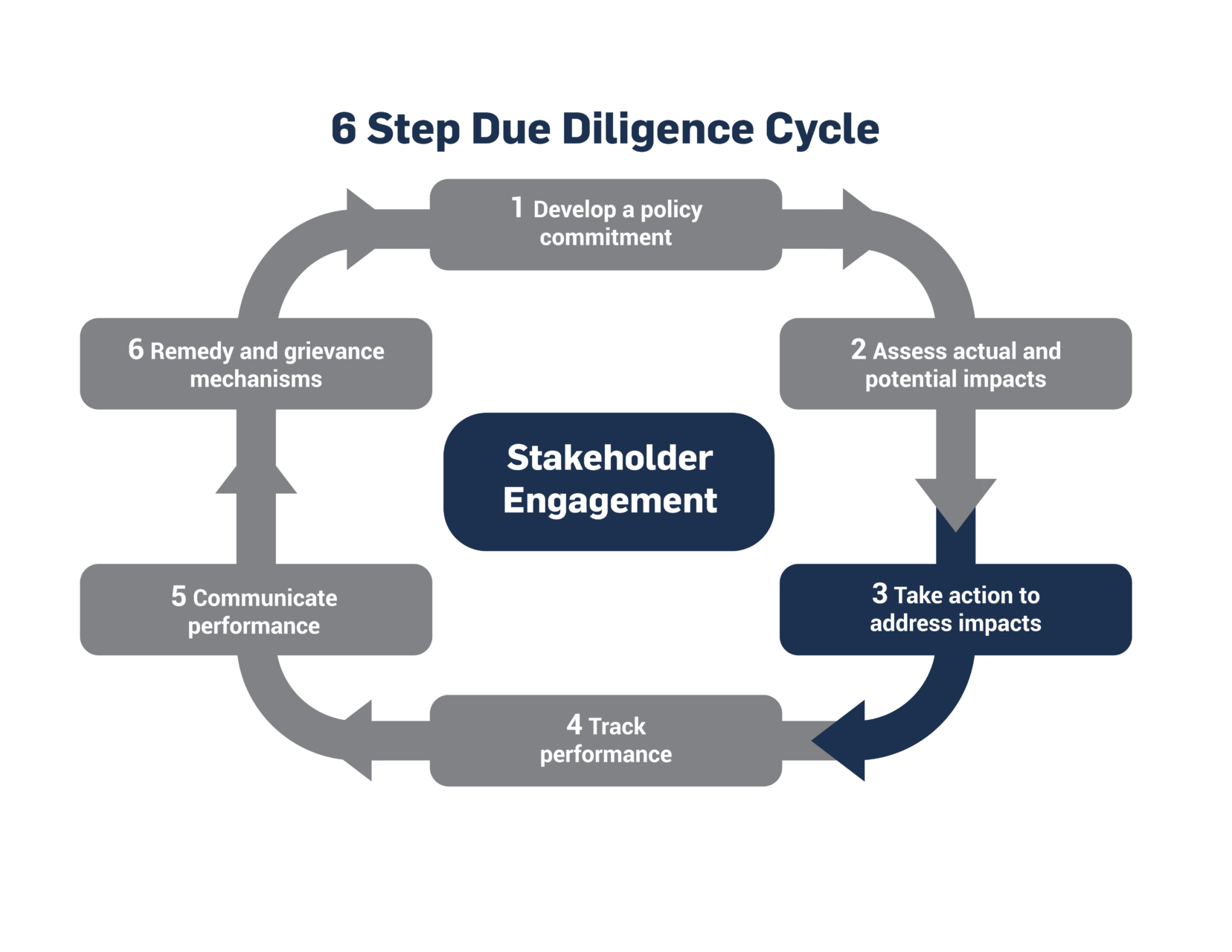

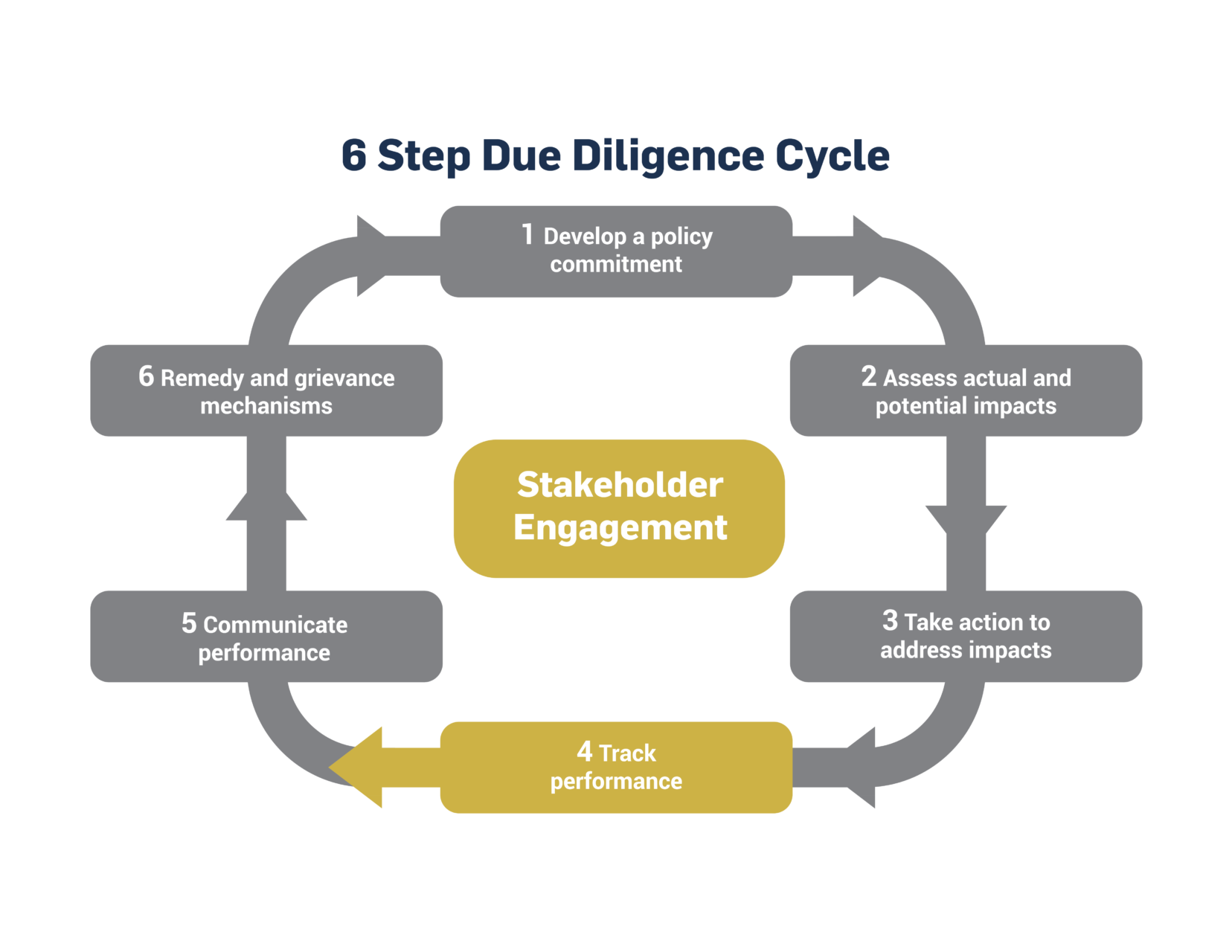

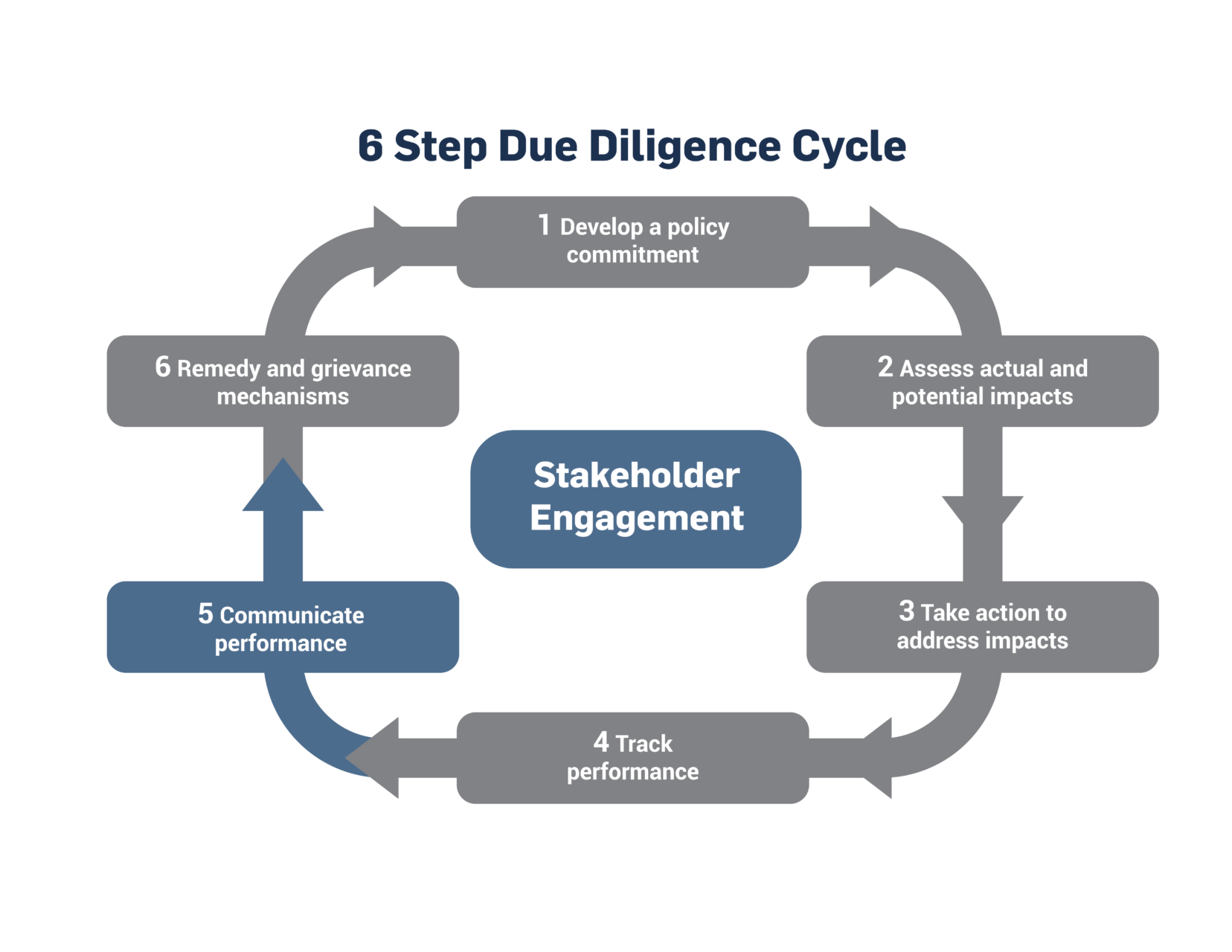

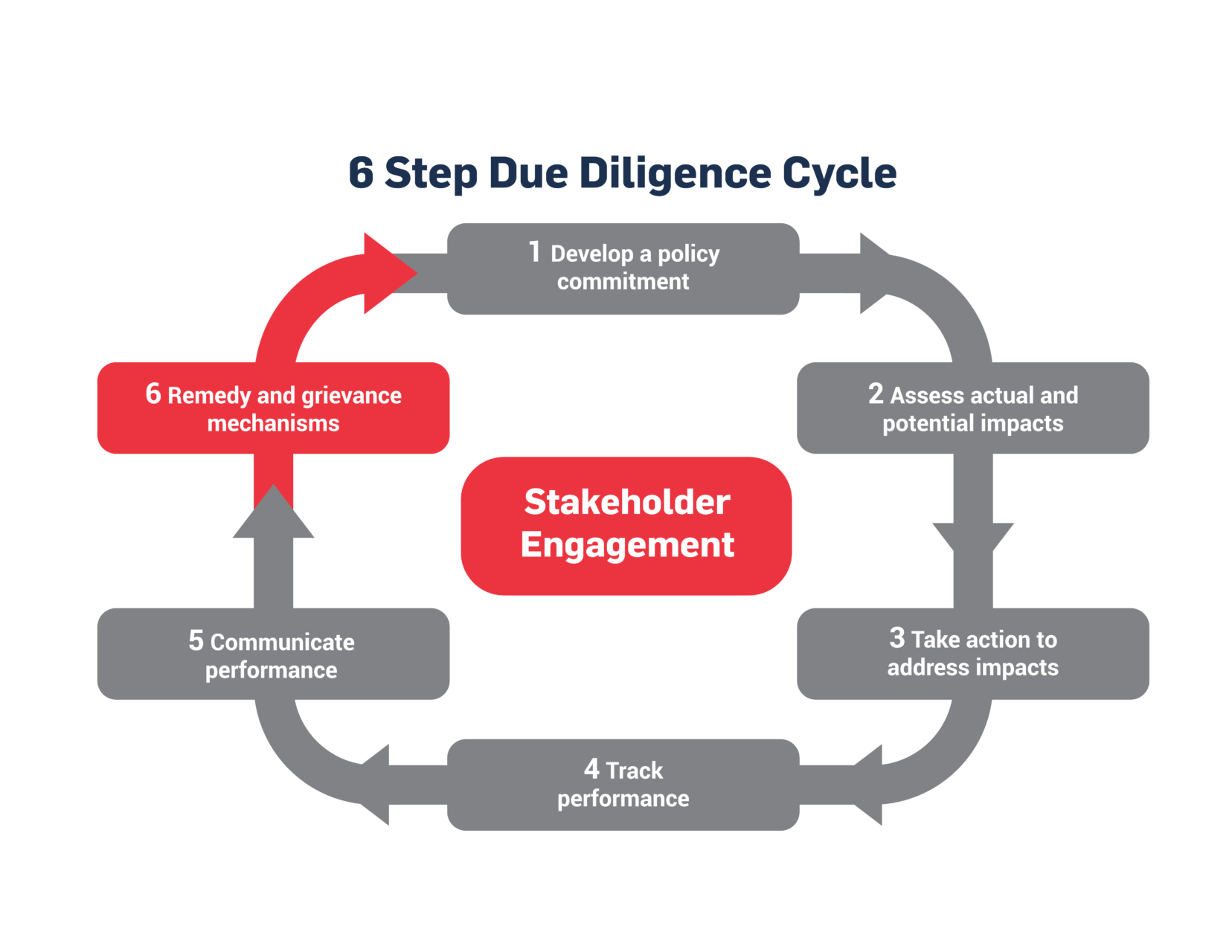

OSH is an important right of all workers across the world and improved transparency and due diligence can ensure that this becomes a reality. This section outlines due diligence steps that companies can take to reduce safety and health risks in their operations and supply chains. The described due diligence steps are aligned with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). Further information on UNGPs is provided in the ‘Key Human Rights Due Diligence Frameworks’ section below or in the Introduction.

While the below steps provide guidance on safety and health risks in particular, it is generally more resource-efficient for companies to ‘streamline’ their human rights due diligence processes by also identifying and addressing other relevant human rights issues (e.g. child labour, forced labour, discrimination, freedom of association) at the same time.

Key Human Rights Due Diligence Frameworks

Several human rights frameworks describe the due diligence steps that businesses should ideally implement to address human rights issues, including working time. The primary framework is the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). Launched in 2011, the UNGPs offer guidance on how to implement the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework, which establishes the respective responsibilities of Governments and businesses — and where they intersect.

The UNGPs set out how companies, in meeting their responsibility to respect human rights, should put in place due diligence and other related policies and processes, which include:

- A publicly available policy setting out the company’s commitment to respect human rights

- Assessment of any actual or potential adverse human rights impacts with which the company may be involved across its entire value chain

- Integration of the findings from their impact assessments into relevant internal functions/processes — and the taking of effective action to manage the same

- Tracking of the effectiveness of the company’s management actions

- Reporting on how the company is addressing its actual or potential adverse impacts

- Remediation of adverse impacts that the company has caused or contributed to

The steps outlined below follow the UNGPs framework and can be considered a process which a business looking to start implementing human rights due diligence processes can follow.

Additionally, the OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises define the elements of responsible business conduct, including human and labour rights.

Another important reference document is the ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy (MNE Declaration), which contains the most detailed guidance on due diligence as it pertains to labour rights. These instruments, articulating principles of responsible business conduct, draw on international standards enjoying widespread consensus.

Companies can seek specific guidance on this and other issues relating to international labour standards from the ILO Helpdesk for Business. The ILO Helpdesk assists company managers and workers that want to align their policies and practices with principles of international labour standards and build good industrial relations. It has a specific section on occupational safety and health.

Additionally, the SME Compass offers guidance on the overall human rights due diligence process by taking businesses through five key due diligence phases. The SME Compass has been developed in particular to address the needs of SMEs but is freely available and can be used by other companies as well. The tool, available in English and German, is a joint project by the German Government’s Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

1. Develop a Policy Commitment on Safety and Health

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, a human rights policy should be:

- “Approved at the most senior level” of the company;

- “Informed by relevant internal and/or external expertise”;

- Specific about company’s “human rights expectations of personnel, business partners and other parties directly linked to its operations, products or services”;

- “Publicly available and communicated internally and externally to all personnel, business partners and other relevant parties”; and

- “Reflected in operational policies and procedures necessary to embed it throughout the business”.

In many countries it is a legal requirement for businesses to have a safety and health policy and associated procedures. However, the extent to which a policy is communicated to workers or suppliers and implemented throughout the business often varies.

A safety and health policy should be informed by the legal requirements in the country the business is registered in, as well as the requirements of other countries that the business operates in. If a business operates in multiple countries and there are higher standards of safety and health or protections for workers, it should be reflected in the policy. Suppliers’ code of conduct should include safety and health requirements alongside other human rights requirements. Because work-related injury can never be fully eliminated, OSH policy should integrate the workers’ protection and cover their compensation in case of loss of earning and need of medical care. For companies operating in multiple countries, OSH policy on workers’ protection and compensation may need to be specified for each country according to local legal requirements.

Examples of stand-alone OSH policies include Marshalls Plc and LEGO Group. Examples of policies that combine OSH with other aspects, like environmental protection, include LG’s ‘Energy, Environment, Safety and Health’ policy and Anglo American’s SHE Way policy (Safety, Health and Environment). OSH commitments are commonly included in supplier or business codes of conduct, such as ASOS’ Supplier Ethical Code, which has OSH requirements for the whole supply chain clearly articulated.

Businesses may also consider aligning their policies with relevant industry-wide or cross-industry policy commitments, for example:

- Responsible Business Alliance (RBA) Code of Conduct

- Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI) Base Code

- amfori BSCI Code of Conduct

- Fair Labor Association (FLA) Code of Conduct

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Helpdesk for Business on International Labour Standards: The ILO Helpdesk for Business is a resource for company managers and workers on how to better align business operations with international labour standards, including OSH. The Q&A section includes answers to the most common questions that businesses consult ILO on, including in relation to company OSH policies.

- United Nations Global Compact-OHCHR, A Guide for Business – How to Develop a Human Rights Policy: This guidance provides recommendations on how to develop a human rights policy and includes extracts from companies’ policies referencing OSH.

- United Nations Global Compact and ILO, Advancing decent work in business through the UN Global Compact Labour Principles: This learning plan, helps companies understand each Labour Principle and its related concepts and best practices as well as practical steps to help companies understand and take action across a variety of issues.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to develop a human rights strategy and formulate a policy statement.

- SME Compass, Policy statement: Companies can use this practical guide to learn to develop a policy statement step-by-step. Several use cases illustrate how to implement the requirements.

2. Assess Safety and Health Impacts

UNGP Requirements

The UNGPs note that impact assessments:

- Will vary in complexity depending on “the size of the business enterprise, the risk of severe human rights impacts, and the nature and context of its operations”;

- Should cover impacts that the company may “cause or contribute to through its own activities, or which may be directly linked to its operations, products or services by its business relationships”;

- Should involve “meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups and other relevant stakeholders” in addition to other sources of information such as audits; and

- Should be ongoing.

Impact assessments should look at both actual and potential impacts, i.e. impacts that have already manifested or could manifest. This compares to risk assessment that would only look at potential impacts and may not satisfy all of the above criteria.

Assessing OSH risks is often a different process to assessing other human rights risks, such as child labour, forced labour or non-discrimination. OSH risk assessments are often legally required. As such, OSH risk assessment methodologies are well established and detailed. Examples of risk assessment guidelines for companies in particular industries or countries include:

- IPIECA Health Risk Assessmentguidelines for companies in the oil and gas industry

- International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM)’s Good Practice Guidance on Occupational Health Risk Assessment

- UK Government’s Health and Safety Executive recommendations on OSH risk assessments

Many companies will also have a clear distinction between the OSH risks of their own operations and those of the supply chain, with the responsibility for the latter being placed on suppliers in most cases. OSH risk assessments on own operations can be detailed as there is oversight of all processes, facilities, activities performed and substances used. Supply chain OSH risk assessments can usually be conducted using quantitative data and country risk profiles, as well as specific risk data on industry activities or known substances.

Safety and health risk assessments may require specialists and technical experts when looking at physical activities within a business and its supply chain. For instance, a supply chain that uses hazardous substances should ensure experts are consulted so the latest information and best practice — that may not be known by individuals in the business — is included. Businesses rarely make their OSH risk assessments public, but some company reports will include risk assessment results or risk profiling of OSH issues, such as Anglo American’s 2020 Sustainability Report.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, 5 Step Guide for Employers, Workers and Their Representatives on Conducting Workplace Risk Assessments: Tips on OSH risk assessments for any industry and for businesses of any size.

- ILO, Guidelines on Occupational Safety and Health Management Systems, ILO-OSH 2001: Guidance on how to draw and implement a workplace system to manage occupational risks.

- ILO, Training Resources on Stress and Ergonomics Risk Assessments: Training resources on workplace risks (including stress prevention and ergonomics) and how to assess them.

- ILO, Statistics on Health and Safety at Work: Information and statistics on OSH issues from a range of countries.

- ILO, Country Profiles on Occupational Safety and Health: Information on country’s OSH profiles, including national laws, regulations, policies and statistics.

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, OSH Barometer: The OSH Barometer is a data visualization tool with up-to-date information on the status of and trends in OSH in European countries, including OSH authorities, national strategies, working conditions and OSH statistics.

- CSR Risk Check: A tool allowing companies to check which international CSR risks (including related to OSH) businesses are exposed to and what can be done to manage them. The tool provides tailor-made information on the local human rights situation as well as environmental, social and governance issues. It allows users to filter by product/raw material and country of origin. The tool was developed by MVO Netherland; the German version is funded and implemented by the German Government’s Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights and UPJ.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to assess actual and potential human rights risks and how to assess and prioritize risks.

- SME Compass, Risk Analysis Tool: This tool helps companies to locate, asses and prioritize significant human rights and environmental risks long their value chains.

- SME Compass, Supplier review: This practical guide helps companies to find an approach to manage and review their suppliers with respect to human rights impacts.

3. Integrate and Take Action on Safety and Health Impacts

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, effective integration requires that:

- “Responsibility for addressing [human rights] impacts is assigned to the appropriate level and function within the business enterprise” (e.g. senior leadership, executive and board level);

- “Internal decision-making, budget allocations and oversight processes enable effective responses to such impacts”.

The actions and systems that a company will need to apply will vary depending on the outcomes of its safety and health risk assessment. Many businesses will follow and establish an OSH management protocol, such as the processes laid out in ISO45001, or other equivalent industry or country standard, such as those of the UK Managing for Health and Safety (HSG65) recommendations. Immediate actions will include embedding policies and protocols into operations to prevent risks and keep workers safe and healthy. This may involve developing new ways of working, buying new machinery or equipment to automate dangerous processes, or adapting processes to make them safer for workers (e.g. changing the protocol for shift patterns to ensure workers get adequate rest in between shifts).

Other examples of taking action on safety and health impacts include:

- Appointment of workers’ safety delegates and workers’ safety and health committees: As provided in ILO Convention on Occupational Safety and Health, 1981, No. 155 and ILO Recommendation on Occupational Safety and Health, 1981, No. 164, and also emphasized in the ILO OSH 2001 Guidelines, cooperation between employers and workers is critical for successfully protecting the safety and health of employees. This may include the appointment of workers’ safety delegates, workers’ safety and health committees, and/or joint safety and health committees with equal representation with employers’ representatives. Such committees or, as appropriate, other workers’ representatives should be given enough information on occupational risks and safety and health measures. These committees should also be encouraged to propose measures on the subject and consulted when major new safety and health measures are envisaged. They should further be able to communicate with workers on safety and health matters during working hours, have reasonable time during paid working hours to exercise their safety and health functions and to receive training related to these functions.

- Safety and health training of employees and suppliers: Another important component of any OSH management system is the information and training of company employees and suppliers, which may cover safety and health laws, company policies, procedures to protect workers, safe use and maintenance of machinery, substances and equipment, and any tailored or additional safety and health procedures for workers with different needs (for instance workers with disabilities or pregnant women). Training can be delivered in a range of formats, such as online videos, e-learns, in-person sessions or supplier round tables.

- For most businesses, all employees will need some form of safety and health training, even if their job is not considered dangerous. For instance, office workers will still require training on how to exit the building safely in the event of an emergency and may receive advice on correct set-up of computer equipment to prevent musculoskeletal injuries from bad posture. Training can also be highly specialized to a worker’s role to ensure they are prepared and able to do their job safely and confidently, such as training for workers operating at height or underground. Other examples of safety and health training can include delivering mental health and well-being training to employees, such as PricewaterhouseCoopers’s (PwC) ‘Green Light to Talk’ campaign.

- Multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) can provide the necessary expertise, guidance and economies of scale to address health and safety challenges in a responsible, sector-specific way. Such MSIs can also help companies learn from different stakeholder groups including business, government, civil society and inter-governmental and non-governmental organizations. Examples include: the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM), which provides roundtable discussions and shared resources to member companies on safety and health issues and best practice; the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, where dozens of fashion retailers are working together to improve safety and health in textile factories following the Rana Plaza disaster in 2013; and the Business Alliance Against Malaria— a coalition of companies working together to promote innovations for a malaria-free world.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Helpdesk for Business on International Labour Standards: The ILO Helpdesk for Business is a resource for company managers and workers on how to better align business operations with international labour standards, including OSH. The Q&A section includes answers to the most common questions that businesses consult ILO on, including in relation to company OSH management systems.

- ILO, Guidelines on Occupational Safety and Health Management Systems (ILO-OSH 2001): These guidelines outline recommendations on OSH management systems and reflect ILO’s tripartite approach and the principles defined in its international OSH instruments.

- ILO, OSH Management System: A Tool for Continuous Improvement: This tool guides businesses through monitoring, evaluating and improving OSH management systems.

- ISO, 45001: Occupational Health and Safety Standard: The first international standard on safety and health, which builds on OHSAS18001 and is structured in a similar way as other ISO management systems (such as ISO 14001 or ISO 9001).

- ILO and United Nations Global Compact, Nine Business Practices for Improving Safety and Health Through Supply Chains and Building a Culture of Prevention and Protection: This report identifies practices that businesses can implement to advance decent work and improve occupational safety and health globally, especially when operating in countries with deficient national safety and health and employment injury protection schemes.

- ILO, SOLVE Training Package: Integrating Health Promotion into OSH Policies: Guidance material on workplace well-being and health issues (such as smoking, stress and HIV/AIDS) includes a trainer’s guide, lesson plans and a participant’s workbook.

- ILO, Occupational Safety and Health within Sustainable Sourcing Policies of Multinational Enterprises: This report gives case studies and examples of how to implement effective and successful OSH practices in international supply chains with a focus on agriculture and textiles.

- The European Agency for Safety and Health at Work provides a list of tools and resources for raising awareness and managing OSH risks, including e-guides on dangerous substances, vehicle safety and stress management.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to take action on human rights by embedding them in your company, creating and implementing an action plan, and conducting a supplier review and capacity building.

- SME Compass, Identifying stakeholders and cooperation partners: This practical guide is intended to help companies identify and classify relevant stakeholders and cooperation partners.

- SME Compass, Standards Compass: This online tool offers guidance on what to pay attention to when selecting sustainability standards or when participating in multi-stakeholder initiatives. It allows comparing standards and initiatives with respect to their contribution to human rights due diligence and their potential limitations.

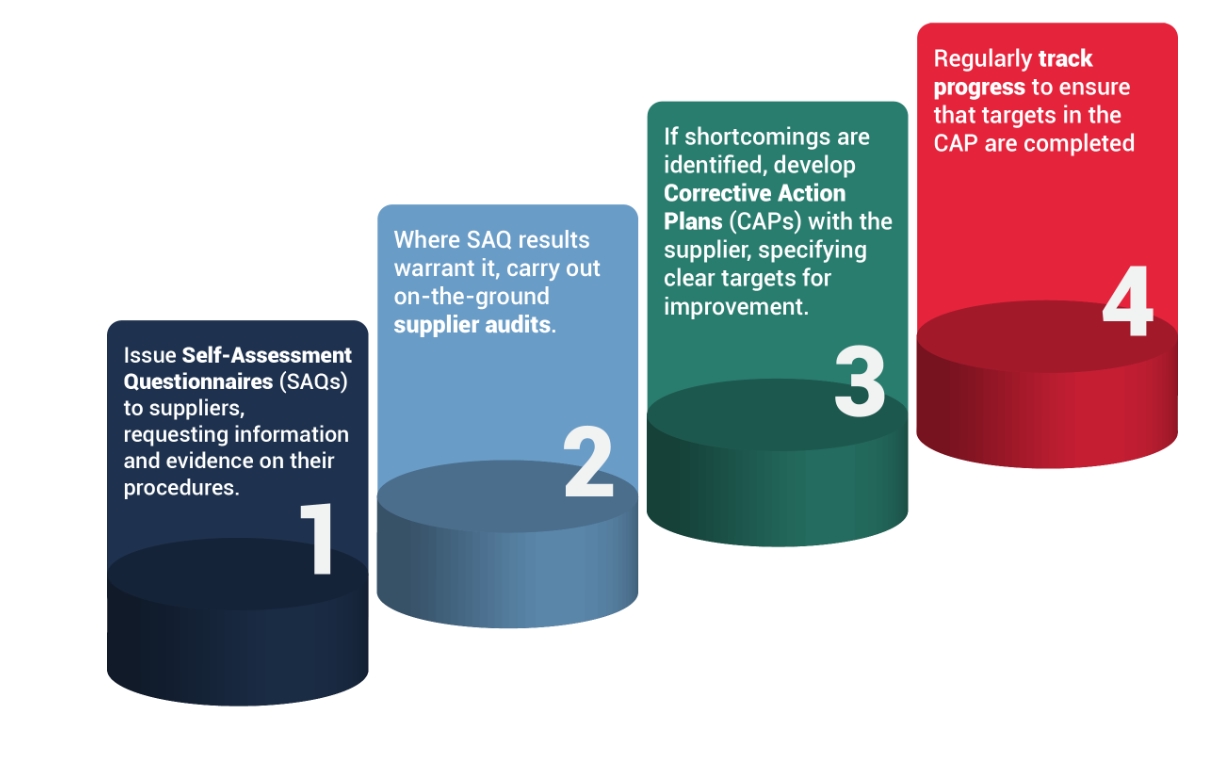

4. Track Performance on Safety and Health

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, tracking should:

- “Be based on appropriate qualitative and quantitative indicators”;

- “Draw on feedback from both internal and external sources, including affected stakeholders” (e.g. through grievance mechanisms).

Businesses should regularly measure their safety and health performance to identify improvement areas. Most businesses regularly collect information on “lagging” safety and health indicators, including:

- Accidents and injuries

- Spills, fires, explosions or safety incidents

- Lost revenue/cost of any such safety incidents

- Deaths

- Lost person-days or recovery time from incidents

- Medical care

- Sick leave requested

- Loss of earning compensation

In addition to monitoring lagging safety and health indicators, businesses are also encouraged to collect information on “leading” safety and health indicators, which are proactive, preventive and predictive measures that provide information about the effective performance of safety and health activities. Examples of leading OSH indicators include:

- Number of workers who attend a monthly safety and health meeting;

- Number of workers asked for feedback on good safety and health goals;

- Number of times each month that top management initiates discussion of a safety and health topic;

- Average score on survey questions related to workers’ perception of management’s safety and health commitment; and

- Number of safety-related line items in budget and percentage of these fully funded each year.

Responsibility for data collection should be clearly allocated to relevant roles within the company and reported with a set frequency (for instance once a month).

Additional monitoring activities could include announced and unannounced audits to check for signs of poor safety and health provision, such as locked doors, unclean work environments, unsafe machinery or operations, or lack of PPE. Such monitoring or audits can be undertaken internally by the company or a third-party contracted by the company. Common supplier audit frameworks that span most industries and include safety and health indicators include SMETA audits and SA8000 accredited audits. Businesses should look for the most appropriate audit type to monitor OSH performance in operations and supply chains, with each industry having different safety and health criteria that should be checked.

Examples of performance tracking on safety and health in supply chains include Inditex, which undertakes numerous OSH audits of suppliers each year. Examples of tracking OSH performance in own operations include Equinox Gold and Total.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Audit Matrix for the ILO Guidelines on Occupational Safety and Health Management Systems: Guidance on topics and criteria to include in OSH audits.

- ICMM, Health and Safety Performance Indicators: Definitions and reporting boundaries for lagging health and safety performance indicators recommended for use by companies in the mining sector.

- ICMM, Overview of Leading Indicators for Occupational Health and Safety in Mining: An overview of the use, measurement and application of leading indicators for OSH in the mining industry.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to measure human rights performance.

- SME Compass: Key performance indicators for due diligence: Companies can use this overview of selected quantitative key performance indicators to measure implementation, manage it internally and/or report it externally.

5. Communicate Performance on Safety and Health

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, regular communications of performance should:

- “Be of a form and frequency that reflect an enterprise’s human rights impacts and that are accessible to its intended audiences”;

- “Provide information that is sufficient to evaluate the adequacy of an enterprise’s response to the particular human rights impact involved”;

- “Not pose risks to affected stakeholders, personnel or to legitimate requirements of commercial confidentiality”.

Companies are expected to communicate their OSH performance in a formal public report. Many countries have national requirements on safety and health reporting for businesses, but there are several global reporting frameworks and standards that can be used, for example the Global Reporting Initiative’s standard GRI 403: Occupational Health and Safety. The standard provides information on what should be included in disclosures on safety and health, and is applicable to businesses in all industries and countries. There are often industry-specific guidance documents available, such as IPIECA resources for the oil and gas industry.

Stand-alone safety and health reports are common in typically dangerous industries such as oil and gas or mining (see Shell’s 2019 Safety report), but safety and health reporting can also be included in sustainability or annual reports (see Nissan’s 2019 report), or in an annual Communication on Progress (CoP) in implementing the Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact.

Safety and health reporting is usually done quarterly or annually, if not more regularly, as it is a material operational consideration for all businesses. Some companies have multiple OSH-related communications, such as Shell that regularly update their safety performance data, have specific website sections for safety and health, and include OSH in their annual and sustainability reports. Alternatively, some companies report safety and health performance in their annual reports. For example, Inditex includes data in their Annual Report and their Annual Statement on Non-Financial Information.

Helpful Resources

- Global Reporting Initiative, GRI Topic Standard Project for Occupational Health and Safety: This resource gives guidance on OSH reporting to meet the requirements of GRI standard 403.

- UNGP Reporting Framework: A short series of smart questions (‘Reporting Framework’), implementation guidance for reporting companies, and assurance guidance for internal auditors and external assurance providers.

- United Nations Global Compact, Communication on Progress (CoP): The CoP ensures further strengthening of corporate transparency and accountability, allowing companies to better track progress, inspire leadership, foster goal-setting and provide learning opportunities across the Ten Principles and SDGs.

- The Sustainability Code: A framework for reporting on non-financial performance that includes 20 criteria, including on human rights and employee rights.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to communicate progress on human rights due diligence.

- SME Compass, Target group-oriented communication: This practical guide helps companies to identify their stakeholders and find suitable communication formats and channels.

6. Remedy and Grievance Mechanisms

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, remedy and grievance mechanisms should include the following considerations:

- “Where business enterprises identify that they have caused or contributed to adverse impacts, they should provide for or cooperate in their remediation through legitimate processes”.

- “Operational-level grievance mechanisms for those potentially impacted by the business enterprise’s activities can be one effective means of enabling remediation when they meet certain core criteria.”

To ensure their effectiveness, grievance mechanisms should be:

- Legitimate: “enabling trust from the stakeholder groups for whose use they are intended, and being accountable for the fair conduct of grievance processes”

- Accessible: “being known to all stakeholder groups for whose use they are intended, and providing adequate assistance for those who may face particular barriers to access”

- Predictable: “providing a clear and known procedure with an indicative time frame for each stage, and clarity on the types of process and outcome available and means of monitoring implementation”

- Equitable: “seeking to ensure that aggrieved parties have reasonable access to sources of information, advice and expertise necessary to engage in a grievance process on fair, informed and respectful terms”

- Transparent: “keeping parties to a grievance informed about its progress, and providing sufficient information about the mechanism’s performance to build confidence in its effectiveness and meet any public interest at stake”

- Rights-compatible: “ensuring that outcomes and remedies accord with internationally recognized human rights”

- A source of continuous learning: “drawing on relevant measures to identify lessons for improving the mechanism and preventing future grievances and harms”

- Based on engagement and dialogue: “consulting the stakeholder groups for whose use they are intended on their design and performance, and focusing on dialogue as the means to address and resolve grievances”

Grievance mechanisms can play an important role in helping to identify and remediate safety and health issues in operations and supply chains. Grievance mechanisms are particularly important in occupational safety and health as issues and risks need to be identified as soon as possible to prevent them from escalating, intensifying or affecting more people. Companies should have grievance mechanisms in place for employees to report issues confidentially, as well as immediate ways to report grievances or incidents such as leaking chemicals or unsafe machinery.

It is important that any safety and health concerns are fixed and remediated as quickly as possible. Often, remediating safety and health problems requires physical intervention (for instance fixing broken machinery), and measures should be put in place to keep workers safe until the problem is fixed. Operating processes or safety and health protocols may need to be changed to prevent this kind of incident from happening again. According to ILO Convention on Occupational Safety and Health, No. 155 (Art.13) workers who have removed themselves from imminent, serious danger to their life and health should be protected from undue consequences.

Businesses may also face significant financial payments to harmed individuals, and if there is a major incident, businesses may face fines and legal actions from criminal or civil action. An example is the Brumadhino dam collapse in Brazil, where 270 workers and local community members were killed. Vale, the company that owns the mine, recently paid out US$7 billion in compensation to the victims and their families, and senior management in the company faced murder charges on the basis that the safety and health mechanisms in place to prevent the dam from collapsing and to protect human life in the event of a collapse were not adequate, if indeed in place.

To avoid such situations and address workers’ protection at the outset, more and more companies are recognizing the need for social insurance schemes and the specific role they could play in strengthening relevant national institutions. In the garment sector, international buyers and retailers have recognized that in cases where national social insurance schemes are not yet developed enough to fully protect all workers against work-related injuries, alternative temporary approaches may be required. These could be temporary time-bound solutions, funded with appropriate financing (which can come from voluntary and time-bound contributions). National tripartite organizations, with ILO support, can help international buyers and retailers in identifying the appropriate financing.

Helpful Resources

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Access to Remedy: Practical Guidance for Companies: This guidance explains key components of the mechanisms that allow workers to submit complaints and enable businesses to provide remedy.

- Global Compact Network Germany, Worth Listening: Understanding and Implementing Human Rights Grievance Management: A business guide intended to assist companies in designing effective human rights grievance mechanisms, including practical advice and case studies. Also available in German.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to establish grievance mechanisms and manage complaints.

- SME Compass, Managing grievances effectively: Companies can use this guide to design their grievance mechanisms more effectively – along the eight UNGP effectiveness criteria – and it includes practical examples from companies.

Case Studies

This section includes examples of company actions to address occupational safety and health in their operations and supply chains.

Further Guidance

Examples of further guidance on occupational safety and health include:

- ILO, The Safeday Report 2020 — In the Face of a Global Pandemic: Ensuring Safety and Health at Work: This report gives specific guidance on how to keep employees and workers safe from COVID-19.

- ILO, How can occupational safety and health be managed?: This guidance provides a range of steps to help businesses manage their occupational safety and health risks.

- ILO, Helpdesk for Business on International Labour Standards: The ILO Helpdesk for Business is a resource for company managers and workers on how to better align business operations with international labour standards, including OSH.

- ILO, Statistics on Health and Safety at Work: Information and statistics on OSH issues from a range of countries.

- ILO, Country Profiles on Occupational Safety and Health: Information on country’s OSH profiles, including national laws, regulations, policies and statistics.

- Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH), Delivering a Sustainable Future: This report maps the key elements of OSH management with the SDG targets.

- Fair Labor Association, Protecting Workers During and After the Global Pandemic: This briefing note provides recommendations to how companies can protect workers’ livelihoods as the world responds to COVID-19.

- SME Compass, Standards Compass: This online tool offers guidance on what to pay attention to when selecting sustainability standards or when participating in multi-stakeholder initiatives. It allows comparing standards and initiatives with respect to their contribution to human rights due diligence and their potential limitations.

- SME Compass, Due Diligence Compass: This online tool offers guidance on the overall human rights due diligence process by taking businesses through five key due diligence phases.SME Compass, Downloads: Practical guides and checklists are available for download on the SME compass website to embed due diligence processes, improve supply chain management and make mechanisms more effective.

- ILO Helpdesk for Business, Country Information Hub: This resource can be used to inform human rights due diligence, providing specific country information on different labour rights.

- ILO and United Nations Global Compact, Nine Business Practices for Improving Safety and Health Through Supply Chains and Building a Culture of Prevention and Protection: This report identifies practices that businesses can implement to advance decent work and improve occupational safety and health globally, especially when operating in countries with deficient national safety and health and employment injury protection schemes.