Created in partnership with the Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights

Working Time

Nearly 480 million people work at least 55 hours a week leading to increased risks of workplace accidents, stroke and ischemic heart disease, regardless of the number of normal hours of sleep.Overview

What is Working Time?

Working time is the period of time that a worker is engaged in paid labour. Adequate working time represents a key element of working conditions and has a great impact on workers’ income, well-being and living conditions.

While more employees working longer hours can help increase business output, productivity (i.e. output per given unit of input) actually decreases. Excessive working time can also cause issues for the business, such as accidents and poor quality of work due to fatigue. Working long hours can lead to negative mental, physical and social effects. It can create problems for workers, such as the inability to enjoy a personal life, undertake academic or professional development and access services such as medical care during opening hours.

Many businesses have a maximum working hours and overtime policy, as well as other policies on breaks during work, rest periods outside of work and paid holidays. However, many countries do not have adequate laws and protections for workers when it comes to working time and wages, and some businesses are able to take advantage of this by requiring workers to do excessive hours or allowing workers to request excessive overtime if their normal wages are not enough to live on. In such cases, international labour standards provisions are an important benchmark for company policies on working time.

Conversely, approximately one fifth of those in global employment work part-time hours of less than 35 hours per week. Proportionally, more people work short hours of work in the least developed countries. This means that many workers are working fewer hours than they would prefer or than they need to survive. Time-related underemployment is often considered a reason for ineligibility for certain social security benefits which are based on meeting minimum working hours thresholds.

New forms of working time, such as compressed workweeks, staggered working time arrangements, annualized working hours, flexi-time and on-call work, offer new opportunities and challenges.

What is the Dilemma?

How does a company ensure it respects relevant international standards and national laws relating to working time when workers are either compelled, have no choice, or operate in a context that makes them accept excessive working time? Workers may be compelled to work longer hours due to production disruptions or excessive orders; or they may seek more hours to earn enough to support themselves and their families. This could also occur in a country where long working hours are accepted culturally or where the Government does not restrict working time or effectively enforce the law.

Ensuring Work-Life Balance Accommodates Family-Friendly Policies

Long working hours affect not only employees but also their families. Family-friendly policies — including paid parental and sick leave, breastfeeding support, affordable and quality childcare, flexible work arrangements and access to minimum social protection measures — are not only linked to better workforce productivity and the ability to attract, motivate and retain employees, but also result in healthier, better-educated children, greater gender equality and sustainable growth. However, for hundreds of millions of workers in global supply chains, basic entitlements that provide them with the time, services and resources to support their families are widely absent.

Working time is a key factor that can either help facilitate work-life balance (e.g. through reductions in working hours and providing certain forms of flexible working time arrangements) or hinder it (e.g. excessively long hours, unpredictable schedules). Businesses can ensure work-life balance by implementing family-friendly policies aligned with international labour standards on work-life balance.

Prevalence of Working Time Violations

A study by the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) showed that in 2016, 479 million people or 9% of the global population were working at least 55 hours/week.

Key trends include:

- The percentage of people working long hours is growing, with consequences for employees’ health. From 2000 to 2016, in relative terms, the proportion of the population working at least 55 hours/week has increased by 9%. Long working hours led to 745,000 deaths from stroke and ischemic heart disease in 2016, a 29% increase since 2000. Excessive working hours have also been found to increase injury risk, regardless of the number of normal hours of sleep.

- An upsurge in flexible, temporary or freelance jobs and ‘gig work’ due to the spread of teleworking, new information and communication technologies, as well as deregulated labour markets, has also increased the trend of increasing working hours. This has led to the blurring of boundaries between working time and rest periods.

- In many parts of the world, there is a significant link between low wages and excessive working time. The ILO reported that the proportion of workers working excessively long hours is more than double in developing countries as compared to developed countries. In developing countries, long working hours are driven mainly by low wages, which means that workers often need to work long hours to make ends meet. Whereas in developed countries, certain categories of professional workers and managers may be expected to work whatever hours are required to complete their assignments and/or may work long hours to show their commitment to the organization and thus advance their careers.

Impacts on Businesses

Businesses can be impacted by working time violations in their operations and supply chains in multiple ways:

- Legal risks can occur if a company does not comply with legal limits on overtime hours or does not pay workers for overtime hours worked. If a worker suffers an accident or ill health due to being overworked, a company may also face legal challenges brought by the individual or a union.

- Operational risks are common when workers are overworked, as they are more likely to make mistakes or underperform in their tasks. This can lead to occupational safety and health incidents at work, accidents while travelling to work (for instance falling asleep while driving home from work after a long shift) and problems with the quality of products being manufactured.

- The well-being of workers can be negatively affected when working hours are excessive and proper breaks or holidays are not taken. Tired and overworked workers are more likely to suffer from physical illnesses, develop mental health issues such as stress and anxiety, make errors due to fatigue or cause accidents in the workplace. This can cause workers to leave a business, have reduced productivity and/or a higher absence or illness rate.

- Reputational damage can be significant when workers’ problems become public. This can cause a reduction in talent acquisition and criticism from shareholders and customers. A recent example is the 100-hour work week expected of summer interns in banks in the UK and USA, which led to claims of exploitation.

- Financial risks: Operational risks can transform into financial risks if they lead to interruptions in internal processes or shortages of supplies, which in turn can disrupt production.

Impacts on Human Rights

Working time violations have the potential to impact a range of human rights,[1] including but not limited to:

- The right to enjoy just and favourable conditions of work (ICESCR, Article 7; UDHR, Article 23): Employees have a right to just and favourable working conditions, including fair wages, equal remuneration for equivalent work, healthy and safe working conditions, the right to rest, leisure, holidays and a reasonable limitation of working hours as part of the conditions of work.

- The right to health (ICESCR, Article 12; UDHR, Article 25; multiple ILO conventions): Employees working long hours, especially over long periods of time, often face long-term risks to their health and safety.

- The right to a family life (ICESCR, Article 10): Working excessive hours can negatively impact a worker’s family life, both in terms of having the time outside of work to meet a partner and start a family, as well as enjoying a family life when one has a family.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The following SDG targets relate to working time:

- Goal 5 (“Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”), Target 5.4: Recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services, infrastructure and social protection policies, and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family as nationally appropriate. Limits on working time provide more time for both women and men to contribute more equally to unpaid care and domestic work.

- Goal 8 (“Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all”), Target 8.8: Protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments of all workers, including migrant workers, particularly women migrants, and those in precarious employment.

Key Resources

The following tools and resources provide further information on how businesses can address working time violations in their operations and supply chains:

- ILO, Working Time in the Twenty-First Century: A report on recent trends and developments relating to working time around the world.

- ILO, Guide to Developing Balanced Working Time Arrangements: A practical guide or ‘how-to’ manual on working time arrangements — also known as “work schedules”.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Base Code Guidance: Working Hours: A step-by-step guide for business to improve working hours in supply chains.

Definition & Legal Instruments

Definition

Working time refers to the amount of time a person a person engages in paid labour in a given time period, including overtime. ILO standards on working time provide the framework for regulating hours of work, daily and weekly rest periods, and annual holidays. Most countries have statutory limits of weekly working hours of 48 hours or less, and the hours actually worked per week in most countries are less than the 48-hour standard established in ILO conventions. These limits serve to promote higher productivity while safeguarding workers’ physical and mental health. Standards on part-time work have become increasingly important instruments for addressing such issues as job creation and promoting equality between men and women.

Legal Instruments

ILO and UN Conventions

Two ILO conventions relate to working time:

- ILO Convention on Hours of Work, No. 1 (1919): The convention is the very first ILO convention. It limits the working week to 48 hours and includes provisions on rest days and overtime.

- ILO Convention on Hours of Work (Commerce and Offices), No. 30 (1930): The convention expands Convention No. 1 to additional industries and workers, including office work and commerce.

Additional ILO Instruments on Working Time

Other relevant ILO instruments on working time include:

- ILO Convention on Forty-Hour Week, No.47 (1935): The convention calls for a 40-hour work week with some limited exceptions.

- ILO Recommendation on Reduction of Hours of Work, No.116 (1962): The recommendation provides guidance on how States can progressively reduce hours of work while maintaining standards of living of workers.

- ILO Convention on Weekly Rest (Industry), No.14 (1921) and ILO Convention on Weekly Rest (Commerce and Office), No.106 (1957): Both conventions require that workers enjoy a rest period of at least 24 consecutive hours in a period of seven days.

- ILO Convention on Holidays with Pay, No.132 (1970): Requires that workers are provided annually at least three working weeks of paid holiday.

- ILO Convention on Night Work, No.171 (1990): The convention lays out requirements for the protection of those who work at night and for women night workers post-pregnancy.

- ILO Convention on Part-time Work, No.175 (1994): The convention requires States to ensure part-time workers get on a pro-rata basis the same working conditions, protection, basic wage and social security as full-time workers.

These conventions have not been widely ratified, except for ILO Convention No.1, which has been ratified by most countries. However, ratification does not ensure that the provision or enforcement of legal protection is of equal efficacy across all countries.

In addition to the ILO instruments, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) also includes relevant provisions regarding hours of work. Article 7 ICESCR affirms the right of everyone to the enjoyment of just and favourable conditions of work including “[r]est, leisure and reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay, as well as remuneration for public holidays”.

Other Legal Instruments

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) set the global standard regarding the responsibility of business to respect human rights in their operations and across their value chains. The Guiding Principles call upon States to consider a smart mix of measures — national and international, mandatory and voluntary — to foster business respect for human rights.

Regional and Domestic Legislation

Companies are increasingly subject to non-financial reporting and due diligence obligations in the jurisdictions in which they operate, which often include disclosures on their performance. There are several high-profile examples of national legislation that specifically mandate human rights-related reporting and other positive legal duties, including the United Kingdom Modern Slavery Act 2015, Australian Modern Slavery Act 2018, the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act 2010, the French Corporate Duty of Vigilance Law 2017, German Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains 2021 and the Norwegian Transparency Act 2022.

Also, in 2021 the Netherlands submitted a Bill for Responsible and Sustainable International Business Conduct, and the European Commission announced its Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). This Directive is likely to come into force between 2025 and 2027 and will make human rights and environmental due diligence mandatory for larger companies.

These mandatory due diligence and disclosure laws require companies to publicly communicate their efforts to address actual and potential human rights impacts, including violations in relation to freedom of association. Failure to comply with these obligations leads to real legal risk for companies.

Contextual Risk Factors

Several factors can lead to long or excessive working hours in business operations and supply chains, including:

- Inadequate legal framework offering a poor standard of protections against excessive working hours. In some countries, labour laws do not limit the number of working hours, though they may advocate ‘standard’ working hours. Therefore, workers are not protected from working more than 48 hours per week as per the maximum defined by the ILO. Although a country may stipulate a standard working week, overtime can be unlimited, leaving workers vulnerable to working excessively long hours without legal protection.

- Poor enforcement of domestic labour laws, including on working hours, due to inadequate training, an under-resourced labour inspectorate or high levels of corruption.

- Cultural acceptance of long working hours in certain industries (e.g. in investment banking) or countries (e.g. Japan) can lead to employees working excessive hours to advance in their careers, often at the expense of a work-life balance or their health and wellbeing. Efforts to shift such cultural acceptances in Japan have intensified over the last two years. Many companies are introducing a four-day working work to try to improve work-life balance and reduce overall working hours.

- Low levels of collective bargaining in specific sectors can increase the risk of long or excessive working hours. Collective bargaining agreements regulate terms and conditions of employment, including guarantees on wages and working hours. In the absence of such agreements, workers may be at risk of working excessive hours, or not receive overtime rates for extra hours worked.

- ‘Zero Hours’ contracts are legal in many countries, where a worker signs a contract of employment with an employer without the guarantee of regular hours of work. This can result in workers needing to work excessive hours in short periods of time when work is available or going weeks without regular hours and thus suffering from low/no income.

- Low wages can lead to longer working hours as workers have to clock more hours to make an adequate wage for themselves or their families. Increased wages or a living wage can help reduce the need for extra hours. Migrant workers in low wage occupations, in particular, are at risk of working excessive hours.

- A large informal workforce can lead to excessive working hours as undocumented or informal workers are unlikely to have contracts or labour protections and are unable to complain if there is a problem. That being said, time-related underemployment is also common in the informal workforce – this is often due to women informally contributing to their family’s income.

- Seasonal or irregular work can lead to periods of excessive or long working hours, driven by the need for companies to produce as much as possible in short deadlines. Examples include harvest seasons for agricultural workers or holiday periods for hospitality workers.

- Cost pressure in internationally operating companies, which is passed on to suppliers, tight lead times and late approval (or continuous alteration) of product specification can lead to excessive overtime in supplier factories.

- Inefficient processes and poor human resource management at supplier factories can further exacerbate the problems with the buying practices of purchasing companies and lead to reduced productivity and ultimately excessive overtime.

- Cost of living spikes amid rising inflation have affected the work-life balance of many workers as inadequate pay increases mean workers are unable to afford basic necessities. Workers in the gig economy are taking on multiple jobs, or starting small businesses to make ends meet – these factors are contributing to a poor work-life balance.

Industry-specific Risk Factors

Multinational companies often come across excessive working hours in their supply chain, where they may not have direct control over production and timelines. This can occur in suppliers’ own operations or, for example, when suppliers contract out some of their work to home workers or smaller factories. Excessive working hours can, however, also occur within company operations — for example, driven by local norms, a culture of excessive working hours (e.g. in the security or services industries ) or by the remoteness of company operations (e.g. in oil and gas). In the maritime travel industry, COVID-19 related travel restrictions have also given rise to extended periods of time beyond working hours and work beyond the expirations of their contracts.

Challenges to ensuring decent working time exist across many industries. High risk sectors include agriculture and fishing, fashion and apparel, electronics manufacturing, financial services, and construction and infrastructure. In particular, the first three sectors pose significant challenges to global sourcing companies. To identify potential risk factors for other industries, companies can access the CSR Risk Check.

Agriculture and Fishing

The agriculture and fishing industries are inherently prone to long or excessive working hours due to the nature of the work undertaken. Industry-specific risk factors include:

- Season-dependent: The seasonal nature of harvests, gestation of animals and migration of fish means that agricultural and fishery work is often concentrated around specific periods of time, resulting in long working hours during those times.

- Piece-rate pay: Many workers will be paid based on the weight or quantity of the goods produced, which further encourages working longer hours to increase income.

- Informal workers: A high proportion of informal workers and family/community workers (who do not have social protections or contracts) increases the risk of excessive working time. These risks are also often gendered, as women and girls are expected to support family farms before undertaking other tasks, while men and boys are more often able to prioritize other activities like school and socializing.

- Time-related underemployment: This can often lead to people working numerous part-time jobs – these jobs add up and the workers face long working hours to make ends meet.

Helpful Resources

- OECD-FAO, Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains: This guidance provides a common framework to help agro-businesses and investors support sustainable development, including improvements in working conditions.

- FAO, Regulating Labour and Safety Standards in the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Sectors: This resource provides information on international labour standards that apply in agriculture, including those on working time.

- SOMO, Labour Conditions at Peruvian Fruit and Vegetable Producers: A report on labour conditions in agriculture in Peru, highlighting forced overtime as one of the most common violations.

- Fairtrade International, Guide for Smallholder Farmer Organisations – Implementing Human Rights and Environmental Due Diligence (HREDD): This guidance was developed to provide advice and tools on HREDD for farmer organisations to implement.

Fashion and Apparel

The fashion and apparel industry is often linked to excessive working hours in supply chains, with employees working between 10 and 12 hours — and sometimes 16 to 18 hours — a day. Industry-specific risk factors include:

- Demand fluctuations: Fluctuations in demand due to the varied output of clothing (winter, spring, autumn and summer), mostly at the beginning of each season, increase the risks of excessive working hours. Companies sourcing from fashion and apparel suppliers may often demand that the products are manufactured within a short time frame. In turn, suppliers are bound by contractual agreementsto honour any commitments made in this respect, but contractual loopholes are often misused by companies to cancel orders and avoid their due diligence obligations. Seasonal work requires that employees work intensively and for long hours in a short space of time to meet demand.

- Forced overtime: Overtime is sometimes forced and often paid below legal requirements. Calculations of overtime payments are often compromised by a lack of social dialogue, poor general communication between workers and managers, and workers’ lack of knowledge about their legal rights to overtime payments.

- Outsourcing: The industry uses a lot of outsourcing and home working, which makes it hard to trace where a product was made and by whom. Informal and home workers often lack labour protections and are vulnerable to excessive working hours.

- Piece-rate pay: Piece-rate pay is pervasive in the garment manufacturing industry and is commonly found among factory-based workers and home-based workers. While research on the impact of piece-rate pay on working hours and overtime is scarce, the pressure for low-wage workers to reach target earnings drives the occurrence of excessive working hours.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Wages and Working Hours in the Textiles, Clothing, Leather and Footwear Industries: This report highlights barriers to decent working hours and has tips for businesses.

- OECD, Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains in the Garment & Footwear Sector: This guidance aims to help fashion and apparel businesses implement the due diligence recommendations contained in the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises to avoid and address the potential negative impacts of their activities and supply chains on a range of human rights, including excessive working hours.

- Human Rights Watch, Paying for a Bus Ticket and Expecting to Fly: How Apparel Brand Purchasing Practices Drive Labor Abuses: This report outlines brands’ sourcing and purchasing practices and suggests that these can be a root cause for labour abuses in apparel factories, including excessive overtime.

- Sedex, Apparel Manufacturing: Sedex Insights Report: This report considers the social, ethical and environmental risks that affect the apparel manufacturing industry, including those related to long working hours/overtime.

Electronics Manufacturing

Electronics manufacturing is also often linked to working time violations, particularly in supply chains. Research by Electronics Watch has found that in China, working weeks of 60-80 hours, including 20-40 hours of overtime, are common in electronics factories.

Industry-specific risk factors include:

- Strict timelines: The problem of excessive working hours in electronics manufacturing is often driven by strict timelines imposed on manufacturers to meet consumer demand.

- Competitive job market: Competition for jobs in the industry can be strong, particularly with respect to famous brands. This can lead to workers being prepared to work excessive hours without adequate rest.

- Student workers: In China, student workers are given compulsory placements in electronics manufacturing factories, modelled as “internships”, where they may be forced to work excessive hours and often go unpaid or earn extremely low wages.

- Forced overtime: Similar to the fashion and apparel industry, overtime is sometimes forced and often paid below legal requirements or industry standards.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Ups and Downs in the Electronics Industry: Fluctuating Production and the Use of Temporary and Other Forms of Employment: A report on the global electronics industry and the impacts of temporary employment on working time and work-life balance among other aspects.

- Electronics Watch, Regional Risk Assessment Electronics Industry, China: A research report on the electronics industry in China highlighting violations of working time as one of many human rights violations in the industry.

- GoodElectronics Network, Labour Conditions at Foreign Electronics Manufacturing Companies in Brazil: Case Studies of Samsung, LGE and Foxconn: A report on labour conditions in the electronics industry in Brazil, highlighting ‘forced overtime’ as one of the most common violations.

- Verité, Forced Labor in the Production of Electronic Goods in Malaysia: A Comprehensive Study of Scope and Characteristics: A report on forced labour in the electronics industry in Malaysia, highlighting ‘forced overtime’ as one of the most common violations.

Due Diligence Considerations

This section outlines due diligence steps that companies can take to prevent working time violations in their operations and supply chains. The described due diligence steps are aligned with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). Further information on UNGPs is provided in the ‘Key Human Rights Due Diligence Frameworks’ section below or in the Introduction.

While the below steps provide guidance on working time in particular, it is generally more resource-efficient for companies to ‘streamline’ their human rights due diligence processes by also identifying and addressing other relevant human rights issues (e.g. child labour, forced labour, discrimination, freedom of association) at the same time.

Key Human Rights Due Diligence Frameworks

Several human rights frameworks describe the due diligence steps that businesses should ideally implement to address human rights issues, including working time. The primary framework is the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). Launched in 2011, the UNGPs offer guidance on how to implement the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework, which establishes the respective responsibilities of Governments and businesses — and where they intersect.

The UNGPs set out how companies, in meeting their responsibility to respect human rights, should put in place due diligence and other related policies and processes, which include:

- A publicly available policy setting out the company’s commitment to respect human rights

- Assessment of any actual or potential adverse human rights impacts with which the company may be involved across its entire value chain

- Integration of the findings from their impact assessments into relevant internal functions/processes — and the taking of effective action to manage the same

- Tracking of the effectiveness of the company’s management actions

- Reporting on how the company is addressing its actual or potential adverse impacts

- Remediation of adverse impacts that the company has caused or contributed to

The steps outlined below follow the UNGPs framework and can be considered a process which a business looking to start implementing human rights due diligence processes can follow.

Additionally, the OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises define the elements of responsible business conduct, including human and labour rights.

Another important reference document is the ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy (MNE Declaration), which contains the most detailed guidance on due diligence as it pertains to labour rights. These instruments, articulating principles of responsible business conduct, draw on international standards enjoying widespread consensus.

Companies can seek specific guidance on this and other issues relating to international labour standards from the ILO Helpdesk for Business. This Helpdesk assists company managers and workers that want to align their policies and practices with principles of international labour standards and build good industrial relations.

Additionally, the SME Compass offers guidance on the overall human rights due diligence process by taking businesses through five key due diligence phases. The SME Compass has been developed in particular to address the needs of SMEs but is freely available and can be used by other companies as well. The tool, available in English and German, is a joint project by the German Government’s Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

1. Develop a Policy Commitment on Working Time

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, a human rights policy should be:

- “Approved at the most senior level” of the company;

- “Informed by relevant internal and/or external expertise”;

- Specific about company’s “human rights expectations of personnel, business partners and other parties directly linked to its operations, products or services”;

- “Publicly available and communicated internally and externally to all personnel, business partners and other relevant parties”; and

- “Reflected in operational policies and procedures necessary to embed it throughout the business”.

Businesses should have a policy that details the maximum working hours for workers, including overtime limits and pay. Workers who have their own contracts are likely to have their hours of work stipulated in the contract. However, many workers globally — particularly in global supply chains — will not have contracts, so it is important for businesses to have clear policies on working time that set company expectations.

Businesses should ensure that their policies comply with local laws in their countries of operation, as well as applicable collective bargaining agreements. Where the local law affords limited protection to workers, company policies should include requirements that are in line with ILO standards — for instance offering more rest days or better overtime rates than local law. Some industries and roles will need to have exceptions for certain roles — such as shift workers or night workers — and should ensure these workers’ rights are also protected.

Some companies have integrated their commitments to decent working time into their human rights policies — for example, Heineken. Where companies do not have a human rights policy, working time is often addressed in other documentation, such as a business code of conduct or ethics and/or a supplier code of conduct (e.g. Inditex). For example, Marks and Spencer outlines working time requirements for its food suppliers in the Sustainability Reference Guide for Suppliers.

Businesses may also consider aligning their working time policies with relevant industry-wide or cross-industry policy commitments, for example:

- Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI) Base Code

- Responsible Business Alliance (RBA) Code of Conduct

- amfori BSCI Code of Conduct

- Fair Labor Association (FLA) Code of Conduct

Businesses may want to check the ILO Helpdesk for Business, which provides answers to the most common questions that businesses may encounter while developing their working time policies — or integrating decent working time commitments into other policy documents.

Helpful Resources

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Base Code Guidance: Working Hours: A step-by-step guide to improving working time for business in supply chains, including chapter 2.1 ‘Revising policies’.

- Sedex/Verité, Supplier Workbook: Chapter 1.7 on working hours includes suggestions on what companies should include in their policies on working time.

- United Nations Global Compact-OHCHR, A Guide for Business: How to Develop a Human Rights Policy: This guidance provides recommendations on how to develop a human rights policy and includes extracts from companies’ policies referencing working time.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to develop a human rights strategy and formulate a policy statement.

- SME Compass, Policy statement: Companies can use this practical guide to learn to develop a policy statement step-by-step. Several use cases illustrate how to implement the requirements.

- United Nations Global Compact, Advancing decent work in business through the UN Global Compact Labour Principles: This learning plan, helps companies understand each Labour Principle and its related concepts and best practices as well as practical steps to help companies understand and take action across a variety of issues.

2. Assess Actual and Potential Impacts on Employee Working Time

UNGP Requirements

The UNGPs note that impact assessments:

- Will vary in complexity depending on “the size of the business enterprise, the risk of severe human rights impacts, and the nature and context of its operations”;

- Should cover impacts that the company may “cause or contribute to through its own activities, or which may be directly linked to its operations, products or services through its business relationships”;

- Should involve “meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups and other relevant stakeholders” in addition to other sources of information such as audits; and

- Should be ongoing.

Impact assessments should look at both actual and potential impacts, i.e. impacts that have already manifested or could manifest. This compares to risk assessment that would only look at potential impacts and may not satisfy all of the above criteria.

Understanding the causes of excessive working hours or overtime is key to addressing the problems and their impacts on workers. This should involve stakeholder participation — including workers, managers and industry representatives in impact assessment studies.

Impact assessments may need to be handled sensitively as some workers may be choosing to work excessive hours or additional overtime due to personal circumstances (such as being the sole provider for a family). Alternatively, some workers may be working excessive hours against their will, under conditions of bonded or forced labour. Discussions with workers, therefore, need to be mindful of these risks to make sure workers are not put at risk or embarrassed to speak about their experiences.

Working time can be addressed in a specific impact assessment or combined with a broader human/labour rights impact assessment (e.g. Nestlé, Unilever and Lidl). Some companies may also choose to conduct a desk-based risk assessment on the likelihood and prevalence of working time violations in their countries of operation and supply chain, which may be helpful to understand a company’s exposure to these risks but may not fully meet the requirements of the UNGPs — including, for example, the requirement to engage with potentially affected stakeholders.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Working Conditions Laws Database: This online database provides information on the regulatory environment for working conditions — including working time — in over 100 countries.

- ILO, Working Time Laws: A Global Perspective. Findings From the ILO’s Conditions of Work and Employment Database: This report provides a comparative analysis of global working time laws, including examining main elements of working time regulation, normal and maximum working hours, overtime work, rest periods and annual holidays.

- ILO, Labour Standards in Supply Chains: How to Meet Them to Become More Competitive and Sustainable: A detailed guide on labour rights, including section 4 on working hours and how to understand excessive working hours causes and impacts.

- ILO, Statistics on Working Time: A collection of data on working time in different countries.

- OECD, Hours Worked: A collection of data on working time in OECD countries.

- CSR Risk Check: A tool allowing companies to check which international CSR risks (including related to excessive working time) businesses are exposed to and what can be done to manage them. The tool provides tailor-made information on the local human rights situation as well as environmental, social and governance issues. It allows users to filter by product/raw material and country of origin. The tool was developed by MVO Netherland; the German version is funded and implemented by the German Government’s Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights and UPJ.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to assess actual and potential human rights risks and how to assess and prioritize risks.

- SME Compass, Risk Analysis Tool: This tool helps companies to locate, asses and prioritize significant human rights and environmental risks long their value chains.

- SME Compass, Supplier review: This practical guide helps companies to find an approach to manage and review their suppliers with respect to human rights impacts.

3. Integrate and Take Action on Working Time

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, effective integration requires that:

- “Responsibility for addressing [human rights] impacts is assigned to the appropriate level and function within the business enterprise” (e.g. senior leadership, executive and board level);

- “Internal decision-making, budget allocations and oversight processes enable effective responses to such impacts”.

The results of the impact assessment should be used to prioritize improvement actions throughout the business and in supply chains. Actions within own operations may include:

- Hiring more employees to reduce the burden of work on the current employees;

- Introducing flexible working hours (e.g. Delland Unilever);

- Supporting workers who might otherwise be compelled to work excessive hours — for example, Avivahas become a Living Hours Employer in the UK, which means low-wage workers have additional protections, such as pay for shifts cancelled outside of an agreed notice period and guaranteed pay for each working week; and

- Analysing production processes, together with workers, to find inefficiencies and areas for improvement.

Whilst taking action on working time may increase costs at first, this may be compensated via increased productivity, which in turn can reduce the need for long working hours. Investing in improving productivity can ultimately benefit workers and result in cost savings for companies.

With regard to supply chains, companies should review their own procurement and ordering practices (going beyond supplier audits) to reduce excessive overtime. Tight lead times, late sample approval and last-minute alterations to product specification put increased pressure on factories to deliver orders by resorting to overtime. On the other hand, poor processes and a low-skilled workforce in supplier factories with high employee turnover may result in low efficiency of production, long overtime hours and low pay.

Setting realistic lead times and sticking to an agreed timescale should be complemented by building suppliers’ capacity to improve productivity and efficiency. These measures could help reduce working time in supply chains without an impact on workers’ wages. This, however, requires a different procurement approach — one that is based not only on cost reduction and compliance but also on long-term capability development. For example, Gap has introduced the Better Buying initiative to address the impact its buying practices have on garment manufacturers’ working time.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Guide to Developing Balanced Working Time Arrangements: A ‘how to’ manual for business and Government bodies for creating working time arrangements that are beneficial for employees and businesses.

- ILO/International Training Centre (ITC), Working Times and Teleworking: This free course familiarizes companies with the concept of decent working time and how to design and implement working time arrangements collaboratively.

- ILO, Labour Standards in Supply Chains: How to Meet Them to Become More Competitive and Sustainable: A detailed guide on labour rights, including section 4 on working hours, which has a helpful self-assessment on working time practices for businesses.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Base Code Guidance: Working Hours: A step-by-step guide to improving working time for business in supply chains, including chapter 2.2 ‘Updating procedures’, chapter 2.3 ‘Training and communication’, chapter 2.4 ‘Implementation in practice’ and chapter 2.5 ‘Documentation’.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Guide to Buying Responsibly: Guidance for companies on purchasing practices, drawing on the findings of a collaborative supplier survey run in partnership between the Ethical Trading Initiatives and the ILO, with support from Sedex. This guide includes best practice examples and outlines five key business practices that influence wages and working conditions, including excessive overtime.

- Sedex/Verité, Supplier Workbook: Chapter 1.7 on working hours includes suggestions on how companies can achieve and maintain high working time standards within their supply chains.

- Impactt Limited, The Impactt Overtime Project: Tackling Supply Chain Labour Issues through Business Practice: This report summarizes the results of a collaborative project in China, which aimed to reduce excessive overtime without reducing wages, through building the factories’ own capacity to improve productivity, human resources management and internal communication.

- United Nations Global Compact, Decent Work Toolkit for Sustainable Procurement: This toolkit enables companies, procurement professionals and suppliers to develop a common understanding on how to advance decent work through purchasing decisions and scaling up efforts to improve lives around the globe.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to take action on human rights by embedding them in your company, creating and implementing an action plan, and conducting a supplier review and capacity building.

- SME Compass, Identifying stakeholders and cooperation partners: This practical guide is intended to help companies identify and classify relevant stakeholders and cooperation partners.

- SME Compass, Standards Compass: This online tool offers guidance on what to pay attention to when selecting sustainability standards or when participating in multi-stakeholder initiatives. It allows comparing standards and initiatives with respect to their contribution to human rights due diligence and their potential limitations.

4. Track Performance on Working Time

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, tracking should:

- “Be based on appropriate qualitative and quantitative indicators”;

- “Draw on feedback from both internal and external sources, including affected stakeholders” (e.g. through grievance mechanisms).

Tracking working time can be done in several ways. Firstly, requesting time sheets or logs from employees gives an indication of working time. However, these may be falsified to hide longer working time. Secondly, it may be helpful to speak to workers in interviews or focus groups. Additionally, multi-stakeholder groups can shed light on working time and practices as workers may not feel comfortable speaking about their hours alone, but more confident when in a group with other workers and civil society or union representatives.

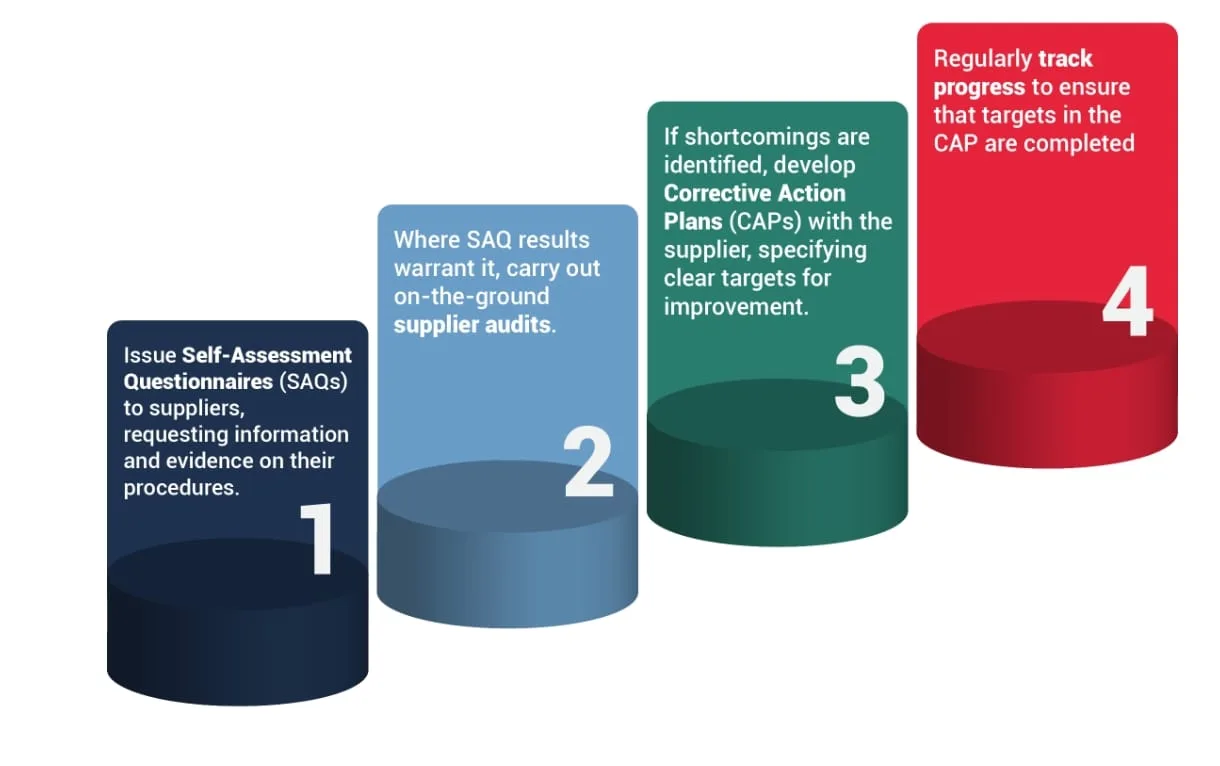

Audits and social monitoring are common ways to check performance in the first tier of the supply chain (e.g. Unilever and Cisco). Such monitoring or audits can be undertaken internally by the company or a third party. A common approach or first step taken by companies is to issue self-assessment questionnaires (SAQs) to suppliers, requesting information and evidence on their working hours. Repeated SAQs can give insight into improvements in supplier management systems and let suppliers self-report on actual or potential impacts.

Where SAQ results warrant it, companies can carry out on-the-ground or (particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic) remote suppliers audits. Common supplier audit frameworks that span most industries and include working time indicators include SMETA audits and SA8000 accredited audits.

If shortcomings are identified, corrective action plans (CAPs) should be developed jointly with the supplier, setting out clear targets and milestones for improvement. Progress should then be tracked regularly to ensure CAP completion. Setting SMART targets helps objectively track performance. SMART targets are those that are: specific, measurable, attainable, resourced and time-bound. Responsibility for data collection should be clearly allocated to relevant roles within the company and reported with a set frequency (for instance once a month).

Although both SAQs and audits are commonly used by companies in various industries, both tools have limitations in their ability to uncover hidden violations, including violations of working time. Unannounced audits somewhat mitigate this problem but even these are not always effective at identifying violations, given that an auditor tends to spend only limited time on-site. Furthermore, human rights violations, including excessive working hours, often happen further down supply chains, whereas audits often only cover ‘Tier 1’ suppliers.

New tools such as technology-enabled worker surveys/‘worker voice’ tools allow real-time monitoring and partly remedy the problems of traditional audits. An increasing number of companies complement traditional audits with ‘worker voice’ surveys (e.g. Unilever and VF Corporation), which can be easily adapted to different languages to accommodate workers’ needs.

Some companies go further and adopt ‘beyond audit’ approaches, which are built on proactive collaboration with suppliers rather than on supplier monitoring (‘carrots’ rather than ‘sticks’). Collaborating with other stakeholders, including workers’ organizations, law enforcement authorities, labour inspectorates and non-governmental organizations to proactively identify, remediate and prevent violations of working time can also prove to be effective in tracking performance on working time. Partnering with other stakeholders to design an effective monitoring mechanism will allow companies to better track progress.

Helpful Resources

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Base Code Guidance: Working Hours: A step-by-step guide to improving working hours for business in supply chains, including chapter 2.6 ‘Monitoring implementation and impact’.

- Sedex/Verité, Supplier Workbook: Chapter 1.7 on working hours includes suggestions on how companies can monitor working time in their supply chains.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to measure human rights performance.

- SME Compass: Key performance indicators for due diligence: Companies can use this overview of selected quantitative key performance indicators to measure implementation, manage it internally and/or report it externally.

5. Communicate Performance on Working Time

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, regular communications of performance should:

- “Be of a form and frequency that reflect an enterprise’s human rights impacts and that are accessible to its intended audiences”;

- “Provide information that is sufficient to evaluate the adequacy of an enterprise’s response to the particular human rights impact involved”;

- “Not pose risks to affected stakeholders, personnel or to legitimate requirements of commercial confidentiality”.

Companies are expected to communicate their performance on working time in a formal public report, which can be achieved via companies’ broader sustainability or human rights reporting (e.g. Unilever, Cisco and Nike), or in their annual Communication on Progress (CoP) in implementing the Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact. Additionally, other forms of communication may include in-person meetings, online dialogues and consultation with affected stakeholders.

Helpful Resources

- UNGP Reporting Framework: A short series of smart questions (‘Reporting Framework’), implementation guidance for reporting companies, and assurance guidance for internal auditors and external assurance providers.

- United Nations Global Compact, Communication on Progress (CoP): The CoP ensures further strengthening of corporate transparency and accountability, allowing companies to better track progress, inspire leadership, foster goal-setting and provide learning opportunities across the Ten Principles and SDGs.

- The Sustainability Code: A framework for reporting on non-financial performance that includes 20 criteria, including on human rights and employee rights.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to communicate progress on human rights due diligence.

- SME Compass, Target group-oriented communication: This practical guide helps companies to identify their stakeholders and find suitable communication formats and channels.

6. Remedy and Grievance Mechanisms

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, remedy and grievance mechanisms should include the following considerations:

- “Where business enterprises identify that they have caused or contributed to adverse impacts, they should provide for or cooperate in their remediation through legitimate processes”.

- “Operational-level grievance mechanisms for those potentially impacted by the business enterprise’s activities can be one effective means of enabling remediation when they meet certain core criteria.”

To ensure their effectiveness, grievance mechanisms should be:

- Legitimate: “enabling trust from the stakeholder groups for whose use they are intended, and being accountable for the fair conduct of grievance processes”

- Accessible: “being known to all stakeholder groups for whose use they are intended, and providing adequate assistance for those who may face particular barriers to access”

- Predictable: “providing a clear and known procedure with an indicative time frame for each stage, and clarity on the types of process and outcome available and means of monitoring implementation”

- Equitable: “seeking to ensure that aggrieved parties have reasonable access to sources of information, advice and expertise necessary to engage in a grievance process on fair, informed and respectful terms”

- Transparent: “keeping parties to a grievance informed about its progress, and providing sufficient information about the mechanism’s performance to build confidence in its effectiveness and meet any public interest at stake”

- Rights-compatible: “ensuring that outcomes and remedies accord with internationally recognized human rights”

- A source of continuous learning: “drawing on relevant measures to identify lessons for improving the mechanism and preventing future grievances and harms”

Many businesses have grievance processes that encompass multiple human and labour rights issues. Grievance mechanisms should be designed to accommodate the needs of workers, and so should be made available in the languages of workers and in accessible formats. Workers may not feel able to report issues to their managers or superiors and should be able to report concerns via other means, such as telephone hotlines or websites. Worker voice technologies are becoming popular ways to empower workers to report violations of their rights. Unions or local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) can also represent effective grievance mechanisms if they are accessible and trusted by workers.

Where businesses find they have overworked employees in their operations or contributed to overwork in their supply chain, remedy must be made. Companies must provide comprehensive remedy that provides missing overtime pay, time-off in lieu of excess hours worked previously, as well as altering contracts and company operating practices so that excessive hours cannot happen again. For example, according to its FLA re-accreditation report, over the period of 2008-2018, Nike has remediated 19 of 21 overtime violations, as well as three out of three violations in which workers were provided no rest day within a seven-day period.

Helpful Resources

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Access to Remedy: Practical Guidance for Companies: This guidance explains key components of the mechanisms that allow workers to submit complaints and enable businesses to provide remedy.

- Global Compact Network Germany, Worth Listening: Understanding and Implementing Human Rights Grievance Management: A business guide intended to assist companies in designing effective human rights grievance mechanisms, including practical advice and case studies.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to establish grievance mechanisms and manage complaints.

- SME Compass, Managing grievances effectively: Companies can use this guide to design their grievance mechanisms more effectively – along the eight UNGP effectiveness criteria – and it includes practical examples from companies.

Case Studies

This section includes examples of company actions to address the problem of excessive working hours and encourage a better work-life balance for workers in company operations and supply chains.

Further Guidance

Examples of further guidance on working time include:

- United Nations Global Compact and UNICEF, Family-Friendly Workplaces: Policies and Practices to Advance Decent Work in Global Supply Chains: A report including suggestions on flexible working time and arrangements to allow for a healthy family life for workers.

- ILO, Overtime Work: A Review of the Literature and Initial Empirical Analysis: A report on overtime and an overview of legal frameworks in six countries: Denmark, Germany, Romania, Spain, Turkey and the UK.

- ILO, Telework in the 21st Century: An Evolutionary Perspective: A review of different national approaches and experiences to teleworking, or remote working.

- ILO, Practical Guide on Teleworking during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond: The purpose of this guide is to provide practical and actionable recommendations for effective teleworking. The guide also includes several case examples regarding how employers and policymakers have been handling teleworking during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- ILO, Working Anytime, Anywhere: The Effects on the World of Work: A report on drivers, incidence/intensity and effects of telework on working time, individual and organizational performance, work-life balance and occupational health and wellbeing.

- ILO, Work Sharing during the Great Recession: New Developments and Beyond: A report outlining the concept and history of work sharing, how it can be used as a strategy for preserving jobs and its potential for increasing employment.

- ILO, Working Time and the Future of Work: A report on trends and developments in working time arrangements and their implications for the future of work.

- ILO, Working Time, Health and Safety: A Research Synthesis Paper: This report provides a synthesis of previous research examining the link between different aspects of working time and outcomes in terms of workers’ health, well-being and workplace safety.

- ILO, Decent Working Time: Balancing Workers’ Needs with Business Requirements: This booklet summarizes five dimensions of decent working time, and how these principles can be put into action.

- ILO and IFC, Better Work Discussion Paper Series, No. 2: Excessive Overtime, Workers and Productivity: Evidence and Implications for Better Work: This paper presents a literature review on the issue of working time regulations and the relationship between excessive overtime and labour productivity, looking at the implications of long working hours on factory performance.

- Our World in Data, Working Hours: This report explores data on working hours across countries, with interactive charts showing working hours throughout history.

- SME Compass, Standards Compass: This online tool offers guidance on what to pay attention to when selecting sustainability standards or when participating in multi-stakeholder initiatives. It allows comparing standards and initiatives with respect to their contribution to human rights due diligence and their potential limitations.

- SME Compass, Due Diligence Compass: This online tool offers guidance on the overall human rights due diligence process by taking businesses through five key due diligence phases.

- SME Compass, Downloads: Practical guides and checklists are available for download on the SME compass website to embed due diligence processes, improve supply chain management and make mechanisms more effective.

- ILO Helpdesk for Business, Country Information Hub: This resource can be used to inform human rights due diligence, providing specific country information on different labour rights.