Created in partnership with the Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights

Gender Equality

It will take over 134 years to achieve equality in terms of women’s economic empowerment and equal participation in the workplace, marketplace and communities.Overview

What is Gender Equality?

Gender equality refers to “the equal rights, responsibilities and opportunities of women and men and girls and boys” according to UN Women, and, as the International Labour Organization (ILO) further notes, “in all spheres of life”, which includes workplace, marketplace and community. Further information on other aspects of equality is provided in the non-discrimination issue.

No country in the world has achieved gender equality. While it is encouraging to see a variety of gender equality efforts across sectors and industries, overall progress has been alarmingly slow. According to the World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Gender Gap Report 2024, it will take over 134 years to achieve equality in terms of women’s economic empowerment and participation. This means it would take over five generations to close the economic gender gap. Due to the ongoing impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, the time required for closing the global gender gap has increased by a generation. The pandemic reversed progress on gender parity in labour-force participation, which had significant impact on how women access economic and other opportunities. Additionally, in 2022 the WEF stated that the projected cost-of-living crisis was likely to more severely impact women than men, as women continue to earn and accumulate wealth at lower levels. In 2023, the WEF confirmed that the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing global crises has been slow for women’s economic empowerment.

Empowering women and girls helps expand economic growth, promote social development and establish more stable and just societies. Women’s economic empowerment is pivotal to the health and social development of families, communities and nations. Further, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) underscore women’s empowerment as an important development objective, in and of itself, and highlight the relevance of gender equality to addressing a wide range of global challenges.

What are the Women’s Empowerment Principles?

Established by the United Nations Global Compact and UN Women in 2010, the Women’s Empowerment Principles (WEPs) are a set of principles offering guidance to business on how to promote gender equality and women’s empowerment in the workplace, marketplace and community. The Principles outline the range of ways that businesses can adopt to ensure that women are respected and supported in their workplaces, across their value chains and in the communities where they operate.

Over 6,000 CEOs have signed the WEPs Statement of Support, and the number continues to grow. Businesses can join the WEPs network by downloading the CEO Statement of Support (available in multiple languages), having it signed by the company’s CEO and attaching it to the online application form.

The WEPs include:

- Principle 1: Establish high-level corporate leadership for gender equality

- Principle 2: Treat all women and men fairly at work — respect and support human rights and

non-discrimination - Principle 3: Ensure the health, safety and well-being of all women and men workers

- Principle 4: Promote education, training and professional development for women

- Principle 5: Implement enterprise development, supply chain and marketing practices that empower women

- Principle 6: Promote equality through community initiatives and advocacy

- Principle 7: Measure and publicly report on progress to achieve gender equality

What is the Dilemma?

The dilemma for businesses is how to ensure that gender discrimination does not occur within their own operations, supply chains and communities given that gender discrimination may be embedded in social norms, local culture and even national laws.

Specific examples of business challenges in the workplace include:

- Operating in a country where women are required to seek approval to work or travel from a male guardian;

- Experiencing difficulties recruiting women for certain positions;

- The culture of hostility of male line workers to a female line manager (including sexual harassment).

Examples of business challenges related to gender equality in the marketplace include:

- Identifying and proactively engaging women-owned businesses;

- Ensuring that suppliers and business partners respect the rights of women and girls;

- Challenging gender stereotypes, rather than perpetuating them, through marketing and advertising.

Finally, examples of gender equality challenges in the community include:

- Operating in and/or sourcing from countries where women entrepreneurs access less capital and fewer resources than their male counterparts;

- Ensuring that investments in community programmes benefit women and girls;

- Operating in and/or sourcing from countries where domestic violence is widespread.

Key Gender Equality Trends

Despite global progress on gender equality over the past few decades, there remain many challenges for women’s and girls’ rights in the workplace, marketplace and community.

Gender equality trends in the workplace:

- Female labour participation rate is lower than that of male workers. The ILO finds that the average global female labour participation rate for 2022 is 52.9%, which is far lower than the figure for men, of 80%.

- Women often receive unequal pay for equal work. The ILO estimates that across the world, women on average continue to be paid about 20% less than men. This is echoed by the UNDP that finds that women earn 77 cents for every dollar that men get for the same work. Moreover, the WEPs Gender Gap Analysis Tool shows that only 52% of companies that used the Tool have a stand-alone policy or a commitment embedded in a broader corporate policy that addresses equal pay for work of equal value.

- Women continue to be promoted less frequently than men. Research from McKinsey suggests that for every 100 men promoted to a manager position, only 86 women are promoted. As a result, men outnumber women significantly at the manager level, which means that there are far fewer women to promote to higher levels.

- Women are under-represented on corporate boards and in C-suite positions. According to 2021 data from Deloitte, women held only 19.7% of board seats and 5% of CEO positions worldwide. Gender imbalance on corporate boards is prevalent in both developed and developing countries.

- Sexual harassment at work is a persistent problem that affects women in all jobs, occupations and sectors of the economy across the world. Estimates suggest that globally as many as 75% of women over 18 — at least two billion women — have experienced sexual harassment.

- Women of colour continue to face significant bias and discrimination at work. While all women are more likely than men to face microaggressions that undermine them professionally — such as being interrupted and having their judgment questioned — women of colour often experience these microaggressions at a higher rate. This highlights the challenges of intersectional discrimination, which occurs when an individual is discriminated against on two or multiple grounds that interact simultaneously and in an inseparable manner.

- The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the care burden on women, with many women forced to reduce their paid working hours or give up their jobs entirely. The UN Global Compact Target Gender Equality COVID-19 quiz data, however, indicates that 79% of companies that took the quiz have assessed (and where needed, adjusted) their policies and practices to support working parents and caregivers. 2022 data also suggests that women are now significantly more burned out — and increasingly more so than men as a result of the pandemic.

Gender equality trends in the marketplace:

- Senior positions in Tier 1 supplier companies are rarely occupied by women. Women hold only 5% of the top-level supply chain positions in Fortune 500 companies. Even in the US and western Europe, only 20% of the top 60 listed companies have a woman as chief procurement officer (CPO).

- Women-owned small and medium enterprises (SMEs) often have to overcome unfavourable lending contexts to access finance. There is a credit gap of approximately US$300 billion for women-owned SMEs. Only 46 economies worldwide require that there is no discrimination in access to credit. Elsewhere, women are often stymied by legal or lending requirements that favour men, such as the requirement for spousal permission to register a company or open a bank account or to provide collateral in the form of deeds where women do not typically inherit property.

- Women-owned businesses struggle to win corporate contracts and access venture finance. According to UN Women, less than 1% of spending by large businesses on suppliers is earned by women-owned businesses. In 2021, research showed that while venture capital funding boomed in 2020, companies founded solely by women received even less investment than in 2019. In the US, female-founded companies raised US$3.31 billion in 2020, or 2.2% of the year’s total sum, compared to US$3.5 billion and 2.6% in 2019.

- Women hold 60–90% of jobs in labour-intensive industries and in 2021 women held 41% of all supply chain jobs globally. Despite this, global businesses rarely focus on women in their procurement strategies. In global supply chains (such as apparel and fresh produce) women often make up the majority of the labour force; however, businesses working with these supply chains are often unaware of the issues that women face and/or unsure how to address them.

Gender equality trends in the community:

- Limited access to education and a large informal sector in many countries push many women towards vulnerable forms of employment. This includes self-employment, usually within the informal economy, or employment within family businesses where labour standards are not likely to be respected. Nearly 15% of employed women — compared with 5.5% of employed men — are contributing family workers where they are self-employed in a business owned or operated by a relative. Such workers are likely to be poorly paid (if at all) and living in poverty, with no employment contract and little access to social protection. ILO statistics show that in developing countries, rates of “time-related underemployment” among women can be as high as 50%. This is where they are likely to work fewer hours than men, but usually not by choice.

- Household and caregiver tasks are often not shared equally. UN Women finds that women are more likely to bear disproportionate responsibility for unpaid care work. On average, women contribute 1–3 hours more a day to housework than men and 2–10 times the amount of time to care for children, the elderly and sick relatives. In the European Union, 25% of women report that the burden placed on them by care and household responsibilities prevents them from being able to enter the labour force.

- Confinement measures arising from the COVID-19 pandemic led to increased or first-time violence and abuse against women and children, while, at the same time, resources to support women experiencing violence were less available and accessible. Data from the UN Global Compact Target Gender Equality COVID-19 Quiz shows that only 26% of surveyed companies have taken action to respond to the increase in domestic violence.

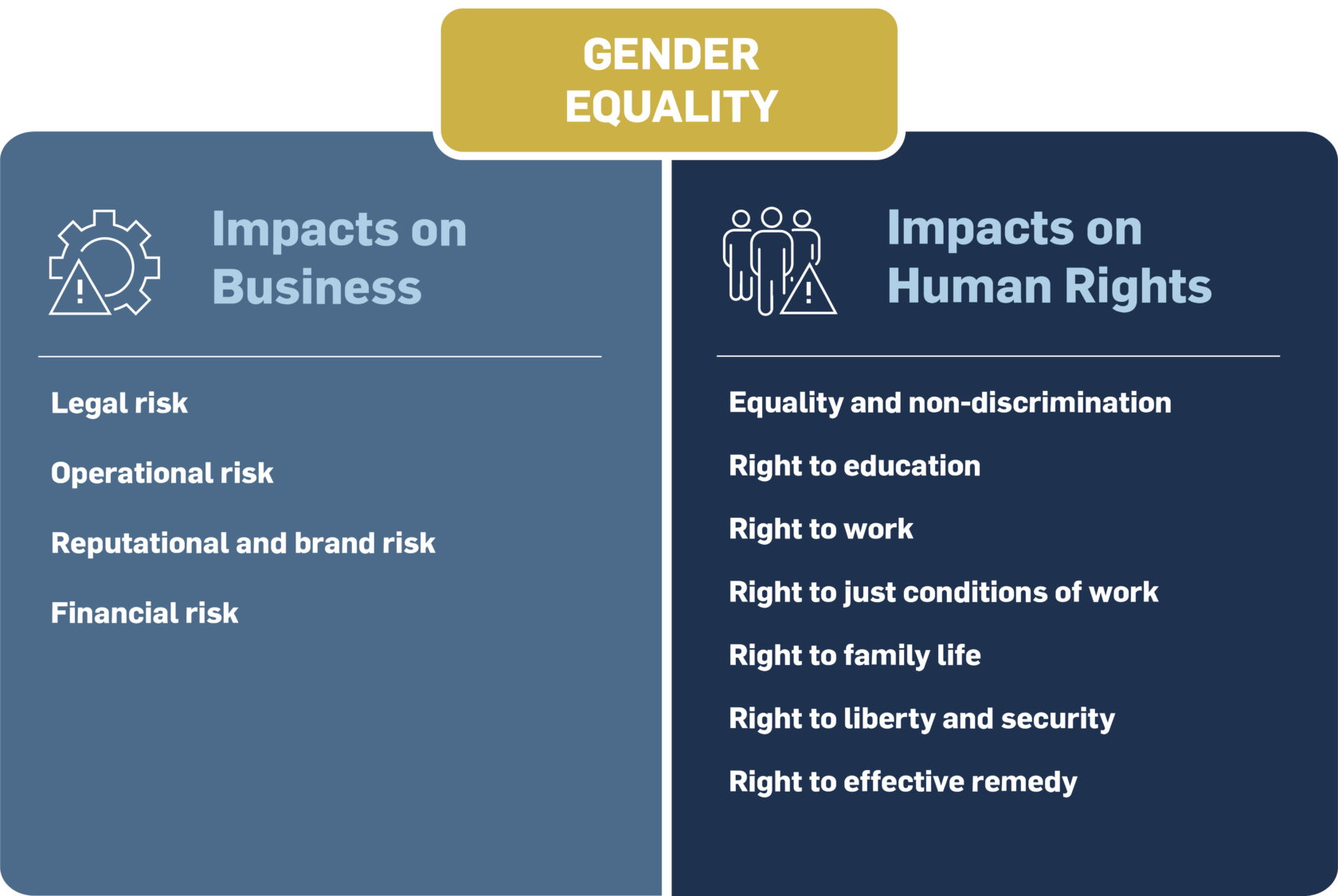

Impacts on Businesses

Companies that focus on women’s empowerment experience greater business success. A growing number of business leaders recognize the importance of women as leaders, consumers, entrepreneurs, workers and caretakers. They are adapting their policies, programmes and initiatives to create environments where women and girls thrive.

Business case for gender equality in the workplace:

- Increased productivity and organizational effectiveness: Strengthening women’s workforce participation and leadership — and preventing sexual harassment in the workplace — can benefit companies in terms of access to improved skills, talent acquisition and retention, employee satisfaction, reduced absenteeism and turnover rates, which can translate into increases in productivity, improved production quality and output, greater innovation outcomes, and access to new markets and customers.

- Increased revenue and profitability: Achieving 30% female representation on corporate boards could add six percentage points to net margins. Research shows that companies in the top quartile for gender diversity on their executive teams are 25% more likely to experience above-average profitability than companies in the fourth quartile. According to research by the ILO, boardrooms with 30-39% women are 18.5% more likely to have improved business outcomes. A 2018 study also showed that businesses founded by women generated twice as much revenue than those founded by men.

- Improved corporate sustainability: In addition to boosting financial performance and economic growth, women’s business leadership is shown to positively impact corporate sustainability performance, leading to reduced greenhouse gas emissions, stronger worker relations, better employee productivity, stronger team performance and innovation, as well as reduced incidences of fraud, insider trading and other unethical practices.

Business case for gender equality in the marketplace:

- Access to a wider variety of high-quality suppliers and reduced procurement costs: Research has found that companies with supplier diversity programmes spend 20% less than competitors on procurement and have lower numbers of procurement staff. Supplier diversity may become a source of a company’s competitive advantage as locking oneself with the same suppliers can be risky.

- Brand reputation and customer loyalty: Consumers are increasingly requesting information from companies regarding their corporate commitment to diversity, inclusion and gender equality in supply chains. Gender-responsive procurement can lead to reputational benefits that attract customer loyalty.

- Improved distribution networks: Women entrepreneurs often have better access to female customers or are better positioned to target the base of the pyramid (BOP) markets. Customer segmentation by gender can enhance companies’ ability to serve women even where substantial barriers limit women’s spending power.

- First-mover advantage: The regions or sectors with the largest gender gaps may offer the largest rewards for closing them. Companies that are among the first to invest in women as customers gain premiums through brand recognition and corporate reputation in the women’s market and through a deep understanding of how to best serve women.

Business case for gender equality in the community:

- Economic growth: It is estimated that US$28 trillion could be added to global GDP by 2025 through investments in gender equality. Gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls is also essential to a wide range of development objectives, including promoting economic growth and labour productivity, enhancing health and education, strengthening resilience to disasters and ensuring more peaceful and inclusive communities.

- Strong investment climate: By investing in women as employees, entrepreneurs and customers, companies support the development of a strong investment climate on the national and/or sectoral level.

- Improved social impact of investments and social license to operate: Reaching out to women as entrepreneurs and customers can benefit companies through improved social impact of their investments and strengthened relationships with local communities (particularly for companies in infrastructure or extractive industries that have large-scale community impact).

On the other hand, businesses can be impacted by discriminatory practices against women — or allegations of gender discrimination — in their operations and supply chains in the following way:

- Legal risk: Legal charges can be brought against the company, up to and including criminal charges, which can result in imprisonment, for example in cases involving sexual assault or harassment in the workplace. The #MeToo movement has triggered a strengthening of laws across the globe on sexual harassment in the workplace, which for many jurisdictions has meant more stringent compliance requirements or greater criminal penalties for companies that fail to take corrective and preventive measures to eliminate sexual harassment.

- Operational risk: Companies that have been implicated in or linked to gender discrimination have witnessed employee protests where staff have participated in mass walkouts. The overall employee turnover and company productivity may be affected negatively if companies pursue gender discrimination practices. Sexual harassment in the workplace has also been linked to reduced profitability and increased labour costs. Finally, gender discrimination can negatively affect talent retention strategies.

- Reputational and brand risk: Campaigns by consumers, civil society organizations, staff members and other stakeholders calling out gender discrimination can result in brand contamination and reputational damage. A reputation as a discriminatory workplace or company can cause workers to leave the company, as well as prevent new talent from applying for roles, potentially resulting in a less diverse and skilled workforce. Research has also found that a single sexual harassment claim could be sufficient to dramatically shape public perception of a company.

- Financial risk: Divestment and/or avoidance by investors and finance providers (many of which are increasingly applying environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria to their decision-making) can result in reduced or more expensive access to capital and reduced shareholder value.

Impacts on Human Rights

Gender discrimination has the potential to impact a range of human rights,[1] including but not limited to:

- Right to equality and non-discrimination (CEDAW, Article 2, UDHR, Articles 1 and 2, ICCPR, Article 26): Women experience discrimination in law and practice. This includes discrimination in economic opportunities as well as access to remedies for human rights violations.

- Right to education (CEDAW, Article 10, UDHR, Article 26, ICESCR, Article 13): This includes the right of equal access to education and equal enjoyment of educational facilities. Women and girls in many countries lack access to educational opportunities due to discrimination and poverty, thus reducing their chances of employment and an independent life.

- Right to work (CEDAW, Article 11, ICESCR, Article 6): Women can be unfairly deprived of employment or arbitrarily dismissed on the basis of their gender or reproductive status. The right to work is closely linked to the rights of just and favourable working conditions and the right to non-discrimination.

- Right to enjoy just and favourable conditions of work (CEDAW, Article 11, UDHR, Articles 23 and 24, ICESCR, Article 7): Women are frequently paid lower wages than men for work of equal value. The right to enjoy just and favourable conditions of work explicitly addresses the right to fair wages and equal remuneration for work of equal value. Particularly, women must be guaranteed conditions of work not inferior to those enjoyed by men. The right to enjoy just and favourable conditions is closely linked to the right to non-discrimination.

- Right to family life (CEDAW, Articles 11 and 16, ICESCR, Article 10): Workplace practices can hinder the ability of working parents to adopt a healthy work/life balance and spend quality time with their families. In some cases, the conditions under which employees work — including issues such as long or irregular hours and inflexible working arrangements — can undermine this right. Article 10.2 ICESCR provides for special protection for mothers during a reasonable period before and after childbirth.

- Rights to liberty and security of person (UDHR, Article 3, ICCPR, Article 9): Discrimination, cultural practices and a lack of safeguards can result in harassment, threats and attacks against women, including Gender-Based and Sexual Violence (GBSV).

- Right to an effective remedy (UDHR, Article 8): Women’s right to an effective remedy for human rights violations can be compromised in countries where the judicial system is inefficient or lacks independence, or where authorities such as the police discriminate against women.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

As the achievement of Goal 5 (gender equality) accelerates and enables progress in other SDGs, it demonstrates the importance of gender equality as a cornerstone of achieving all dimensions of inclusive and sustainable development. In short, all the SDGs depend on the achievement of Goal 5. All 17 goals contain a gender equality perspective that helps frame progress in terms of achieving women’s and girls’ rights.

A number of SDG targets relate specifically to gender equality. The following considerations illustrate the interconnected nature of Goal 5 to other SDGs:

- Ending all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere (Target 5.1) is directly linked to the achievement of several other SDGs, namely Goals 1 (No poverty), 2 (End hunger), 3 (Good health and well-being), 4 (Quality education), 8 (Decent work and economic growth) and 10 (Reduced inequalities). For example, ensuring universal access to sexual and reproductive health-care services (Target 3.7) is an important step towards ending discrimination against women. Ending discrimination against women and girls also contributes towards promoting inclusive and sustainable industrialization (Target 9.2) and ensuring responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels (Target 16.7)

- By recognizing and valuing unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services (Target 5.4), greater social, economic and political inclusion for women will be achieved (Target 10.2).

- By ensuring women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic, and public life (Target 5.5), women will have equal rights to economic sources (Target 1.4) and full and productive employment and decent work (Target 8.5).

- Undertaking reforms to give women equal rights to economic resources (Target 5.a) will go towards the progress of climate action (Goal 13). By empowering women to have greater access to land, credit and essential inputs such as fertilizers, irrigation, technology and market, women will be able to tap into climate change adaptation practices that require the use of technical advances on heat-resistant and water-conserving crop varieties.

Key Resources

The following resources provide further information on how businesses can address gender discrimination and empower women across the workplace, marketplace and community:

- Women’s Empowerment Principles, Resources: The WEPs website has an extensive collection of resources on gender equality, including frameworks, templates, reports, guidance and toolkits that companies can utilize in the design, implementation and monitoring of their gender equality programmes. In addition, the virtual platform WEPs Learn offers lessons designed to give women more confidence in job interviews, lead gender equality initiatives within their organizations, the ability to assess new job opportunities and grow their careers more effectively.

- UN Women, Digital Library: A comprehensive resource on gender equality including reports, discussion papers and case studies.

- ILO-UN Women, Empowering Women at Work: Company Policies and Practices for Gender Equality: This resource provides suggestions on how companies can promote gender equality in their operations, with reference to international labour standards and guiding principles. ILO and UN Women have also published another resource on promoting gender equality in supply chains.

Definition & Legal Instruments

Definition

The UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), often described as an international bill of rights for women, reaffirms the principle of equality between women and men. CEDAW defines what constitutes discrimination against women in various areas and sets up an agenda for national action to end such discrimination.

The right to be free from discrimination, including on the basis of sex, is also firmly secured in other international human rights instruments, including UDHR, ICCPR and ICESCR. In addition, a number of UN instruments tackle specific aspects related to gender equality, including:

- Gender-based violence: Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women

- Trafficking of women: Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children

The elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation is one of the ILO’s five fundamental rights and principles at work which Member States have to promote regardless of whether they have ratified the respective conventions. Two ILO conventions address the issue of discrimination:

- ILO Discrimination (in Employment and Occupation) Convention, No. 111 (1958) requires ratifying countries to enforce national policies to promote respect and equal opportunities in the workplace and identifies race, colour, sex, religion, political opinion, national extraction and social origin as bases of discrimination.

- ILO Equal Remuneration Convention, No. 100 (1951) promotes the principle of equal pay for work of equal value.

Other relevant ILO instruments on gender equality include the following:

- Workers with Family Responsibilities Convention (No. 156)

- Home Work Convention (No. 177)

- Maternity Protection Convention, (No. 183)

- Violence and Harassment Convention, (No. 190)

While most States have ratified ILO conventions No.111 and No.100, their implementation in national laws and enforcement of such laws vary greatly. In practice, the provision of legal protection against discrimination in respect of employment and occupation is not consistent across countries.

The Istanbul Convention (2011), a Council of Europe treaty, establishes state responsibility to prevent all forms of violence against women, protect those who experience it and prosecute perpetrators. The convention has been ratified by 34 Member States of the Council of Europe, who must adopt measures to fulfil their commitment to end violence against women and domestic violence. Countries outside the Council of Europe have expressed interest in signing, which is a possibility under the convention.

In November 2022, the EU adopted Directive 2022/2381, a new law on gender balance on corporate boards, establishing new targets for listed companies to have 40% women among non-executive directors or 33% among directors.

Legal Instruments

The UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), often described as an international bill of rights for women, reaffirms the principle of equality between women and men. CEDAW defines what constitutes discrimination against women in various areas and sets up an agenda for national action to end such discrimination.

The right to be free from discrimination, including on the basis of sex, is also firmly secured in other international human rights instruments, including UDHR, ICCPR and ICESCR. In addition, a number of UN instruments tackle specific aspects related to gender equality, including:

- Gender-based violence: Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women

- Trafficking of women: Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children

Two ILO conventions address the issue of discrimination:

- ILO Discrimination (in Employment and Occupation) Convention, No. 111 (1958) requires ratifying countries to enforce national policies to promote respect and equal opportunities in the workplace and identifies race, colour, sex, religion, political opinion, national extraction and social origin as bases of discrimination.

- ILO Equal Remuneration Convention, No. 100 (1951) promotes the principle of equal pay for work of equal value.

Other relevant ILO instruments on gender equality include the following:

- Workers with Family Responsibilities Convention (No. 156)

- Home Work Convention (No. 177)

- Maternity Protection Convention, (No. 183)

- Violence and Harassment Convention, (No. 190)

While most States have ratified ILO conventions No.111 and No.100, their implementation in national laws and enforcement of such laws vary greatly. In practice, the provision of legal protection against discrimination in respect of employment and occupation is not consistent across countries.

ILO Violence and Harassment Convention No. 190 is the first international treaty to recognize the right of everyone to a workplace free from violence and harassment, including gender-based violence and harassment. The Convention, adopted in June 2019, requires State parties to put in place the necessary laws and policy measures to prevent and address violence and harassment in the world of work. The Convention represents a historic opportunity to shape a future of work based on dignity and respect for all.

Regional and domestic legislation

The Istanbul Convention (2011), a Council of Europe treaty, establishes state responsibility to prevent all forms of violence against women, protect those who experience it and prosecute perpetrators. The convention has been ratified by 34 Member States of the Council of Europe, who must adopt measures to fulfil their commitment to end violence against women and domestic violence. Countries outside the Council of Europe have expressed interest in signing, which is a possibility under the convention.

In November 2022, the EU adopted Directive 2022/2381, a new law on gender balance on corporate boards, establishing new targets for listed companies to have 40% women among non-executive directors or 33% among directors.

Companies are increasingly subject to non-financial reporting and due diligence obligations in the jurisdictions in which they operate, which often include disclosures on their performance. There are several high-profile examples of national legislation that specifically mandate human rights-related reporting and other positive legal duties, including gender equality provisions: German Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains 2021 and the Norwegian Transparency Act 2022. France’s Rixain Law 2021 specifically strengthens regulations to support gender equality in the workplace through gender-based quotas and expanded reporting requirements.

Also, in 2021 the Netherlands submitted a Bill for Responsible and Sustainable International Business Conduct, and the European Commission announced its Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). This Directive is likely to come into force between 2025 and 2027 and will make human rights and environmental due diligence mandatory for larger companies.

These mandatory due diligence and disclosure laws require companies to publicly communicate their efforts to address actual and potential human rights impacts, including violations in relation to freedom of association. Failure to comply with these obligations leads to real legal risk for companies.

Non-discrimination is included as one of the Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact: “Principle 6: Businesses should uphold the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation”. The four labour principles of the UN Global Compact are derived from the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work.

These fundamental principles and rights at work have been affirmed and developed in the form of specific rights and obligations in International Labour Conventions and Recommendations and cover issues related to child labour, discrimination at work, forced labour and freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining.

Member States of the ILO have an obligation to promote non-discrimination, even if they have not ratified the Conventions in question, as the rights and principles at work are universal and they apply to all people in all States.

Contextual Risk Factors

The elimination of gender discrimination and the advancement of gender equality in the workplace, marketplace and community requires an understanding of underlying causes and the consideration of a wide range of issues. Key risk factors include:

- Widespread societal/cultural acceptance of gender discrimination: Deeply entrenched discrimination against women and girls transmits practices that inhibit women’s and girls’ rights. Social acceptance of domestic violence or social expectations that women manage childcare and all household responsibilities perpetuate discriminatory attitudes towards women.

- Laws and regulations: In some countries, women are actively and directly discriminated against through laws and regulations. Women may face state-sanctioned discrimination such as gender-biased legislation relating to access to education, credit, land ownership, inheritance rights or equal pay.

- Poorly enforced domestic labour laws: Due to a lack of government will, resources and/or capacity, poorly enforced domestic labour laws can lead to discrimination occurring in the workplace, marketplace and community without any remediation as the legal system to address discrimination may be weak.

- High levels of economic disparity between men and women: Women face unequal pay in most countries and are also at a higher risk of performing undervalued work (such as domestic work), putting them at a more vulnerable economic position than men. They are also much more likely to perform unpaid work such as domestic labour and childcare. These aspects can limit their decision-making powers or inhibit their access to opportunities such as education, capital or land.

- Limited access to education: Women continue to face significant barriers in accessing education in many countries. This pushes many women towards vulnerable forms of employment, for example in the informal economy, where they are over-represented compared to men and where they are at higher risk of rights violations and being excluded from social protections.

Industry-specific Risk Factors

Gender discrimination and violations of women’s rights occur in virtually every sector. In some sectors, the job functions that women work in also make them more vulnerable. The following sectors are chosen as examples to illustrate gender discrimination issues prevalent in many other sectors. To identify potential gender discrimination risks for other industries, companies can access the CSR Risk Check.

Agriculture and Fishing

Although in some countries, women make up most of the agricultural labour force, they continue to face specific disadvantages due to entrenched practices of gender discrimination.

Agriculture-specific risk factors include the following:

- Land ownership disparity: According to the UN, women make up an estimated 43% of the agricultural labour force but on average own less than 20% of land globally. For example, in India, despite women constituting 65% of the total agricultural workforce, the majority do not enjoy official legal recognition as farmers and therefore face significant barriers to equal access to resources. The lack of equal rights faced by women farmers is a significant barrier to women accessing credit or subsidies, and can preclude them from engaging in negotiations to receive fair compensation for the use or purchase of their land. Compensation payments are typically paid to the male head of household, thereby subjecting women to increased food insecurity and economic dependence on men.

- Subsistence production: Women tend to be mostly involved in subsistence production within agriculture, whereas men are mostly involved in commercial crops. This is a significant driver in the gender pay gap faced by women in the sector.

- Sexual harassment and violence: Women, particularly female migrant workers, are at risk of exploitation, sexual harassment and violence in the agriculture sector. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated conditions for these workers due to decreased checks and enforcement. Media reports have highlighted that women migrant workers, particularly undocumented migrant workers, in the sector are considered to be most at risk of situations of isolation, segregation and dependency on an employer. Labour exploitation is also often accompanied by employers’ sexual blackmail towards female migrant workers.

- Poor access to education in rural areas: The gender gap in education is particularly acute in rural areas, where most agriculture takes place, with female household heads having less than half the years of education of their male counterparts. Lower literacy rates contribute to the marginalization of women in bargaining power during land acquisition. The lack of educational opportunities and the rural poverty cycle drives child labour in agriculture. Both boys and girls work in fields and are often isolated for long hours, facing the risk of violence and abuse. Additionally, country-specific evidence shows that girls frequently work more hours than boys, and a higher percentage of girl child labourers are unpaid or are paid less.

Helpful Resources

- FAO-IFAD-ILO, Gender Dimensions of Agricultural and Rural Employment: Differentiated Pathways out of Poverty: Status, Trends and Gaps: This resource explores key drivers behind gender inequality in agricultural employment.

- FAO, Women in Agriculture: Closing the Gender Gap for Development: This report looks at the business case for investing in women in agriculture.

- FAO, Regulating Labour and Safety Standards in the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Sectors: This resource provides information on international labour standards that apply in agriculture, including those on discrimination (against women and other vulnerable groups) in employment and occupation.

- UN Women, Women’s Economic Empowerment in Fisheries in the Blue Economy of the Indian Ocean Rim: A Baseline Report: This report, developed in collaboration with the International Collective in Support of Fishworkers (ICSF), examines the roles of women in fisheries and aquaculture in the Indian Ocean Rim region and the challenges and opportunities for their economic empowerment.

- UN Women, Sexual Harassment in the Informal Economy: Farmworkers and Domestic Workers: This discussion paper identifies sector-specific challenges to ending sexual harassment in farm work and includes examples of how women’s and workers organizations have tackled this problem.

- World Bank-FAO-IFAD, Gender in Agriculture Sourcebook: Companies may use this resource as a guide in addressing gender issues and integrating gender-responsive actions in the design and implementation of agricultural projects.

- World Resources Institute, Making Women’s Voices Count In Community Decision-Making On Land Investments: This working paper presents findings from a project to promote gender-equitable community decision-making on land investments in Mozambique, Tanzania and the Philippines, three countries that are among the most targeted for land investments in the global South. Specific reforms are recommended for each country and outreach and advocacy strategies are discussed.

- Fairtrade International, Guide for Smallholder Farmer Organisations – Implementing Human Rights and Environmental Due Diligence (HREDD): This guidance was developed to provide advice and tools on HREDD for farmer organisations to implement.

Mining and the Extractives Industry

The extractives sector remains a male-dominated industry, with gender disparities evident at every level; for example, women account for just 15% of leadership roles in the mining sector. In extractive communities, women disproportionately suffer from the environmental and social impacts of the industry.

Risk factors specific to the extractives sector are as follows:

- Under-representation of women: Women are under-represented in leadership positions and in the mining workforce. In industrial mining, women typically earn on average 40% less, and women in artisanal and small-scale mining operations are often pigeonholed into lower-paid and less valued roles.

- Limited inclusion of women in decision-making: According to the World Bank’s survey of women working in, around, or with the mining sector, the primary challenge is limited inclusion of women in decision-making. In highly patriarchal societies, women are represented at even lower rates in decision-making discussions and are rarely consulted or informed about decisions, with the assumption that women are represented by their male family members and community leaders. Women also struggle to share their feedback through grievance mechanisms both due to fears of stigmatization and retaliation, and because they would be expected to issue grievances through male representatives speaking on their behalf.

- Land ownership: Land acquisition and resettlement/displacement resulting from extractive operations have greater impacts on women due to cultural and legal barriers that inhibit women from formally owning or inheriting land. In some cases, these obstacles preclude women from engaging in bargaining negotiations or receiving appropriate compensation when displaced. With the loss of land, women may be unable to meet the subsistence needs of their families and thus become more economically dependent on men.

- Sexual and gender-based violence rates: Rates of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are typically higher in mining communities. The Danish Institute for Human Rights reports that in communities facing influxes of transient and typically male workers with disposable income, the subsequent changes in social dynamics often result in an uptick of substance abuse, sexual harassment, domestic violence, sexual violence and STIs. The Institute also notes that indigenous women are more vulnerable to SGBV than non-indigenous women.

- Lack of safety equipment appropriate for women: Women in mining may find that their safety is compromised because the mining gear and equipment is designed to accommodate men. These oversights endanger women in the workplace; according to the Responsible Mining Foundation, women’s work is riskier and more difficult when forced to make do with ill-fitting safety equipment and protective gear.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Women in Mining: Towards Gender Equality: This brief offers guidance on how to revise and update outdated legislation, and to formulate and implement an integrated and coherent package of policies and measures to advance gender equality and decent work in mining.

- International Finance Corporation, Unlocking Opportunities for Women and Business: This dynamic toolkit provides guidance for business units to address gaps in their gender approach within the workforce and community.

- The World Bank, Extracting Lessons on Gender in the Oil and Gas Sector: A Survey and Analysis of the Gendered Impacts of Onshore Oil and Gas Production in Three Developing Countries: This paper explores the existing gender inequalities in the industry, the ways that the industry perpetuates these inequalities, and recommendations for reducing these gaps.

- The World Bank, Impactful Women: Examining Opportunities and Constraints for Women in Mining Organizations Worldwide: This report presents findings from a research project on Women in Mining (WIM) organizations and suggests that the most critical challenges facing women in the mining sector include the lack of women’s participation in decision-making, women’s limited access to leadership positions and inadequate workplace safety, including gender-based violence and sexual harassment.

- The Danish Institute for Human Rights, Towards Gender-Responsive Implementation of Extractive Industries Projects: This report outlines key challenges facing women in the extractives industry, and provides best practices and resources to address these issues and implement gender-responsive approaches.

- The Advocates for Human Rights, Promoting Gender Diversity and Inclusion in the Oil, Gas and Mining Extractive Industries: This report examines women’s participation in the extractives workforce and the impact of extractives on women in local communities. It identifies underlying causes of these issues and provides recommendations to address them.

- University of Queensland and Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, Mining and Local-Level Development Examining the Gender Dimensions of Agreements Between Companies and Communities: This report explores the challenges and opportunities associated with negotiating and implementing agreements between companies and communities by considering issues relating to gender and local-level development, with a focus on Australian mining companies.

- Oxfam, A Guide to Gender Impact Assessment for the Extractive Industries: This tool seeks to ensure women’s voices are meaningfully included in decision making for extractive industry projects.

Apparel Manufacturing

The apparel manufacturing industry is among the largest employers of female workers, particularly in lower-income countries, where women account for approximately 80% of the garment sector workforce.

Risk factors specific to the apparel manufacturing sector are as follows:

- Informal employment: The apparel manufacturing sector is heavily reliant on women who are employed informally, who lack social protections and face the risk of more exploitative working conditions as a result. Informal workers who are without formal contracts are at a higher risk of unstable work, exclusion from trade union membership and increased risk of violence and harassment. Estimates of informality in the garment value chain range from 50% to 80%, with the overwhelming majority being female employees. Home-based workers, typically female, may also be subject to unpaid or underpaid work.

- Sexual harassment in garment factories: The ILO reports that sexual harassment is a relatively common occurrence in garment factories. Most workers in garment factories are females under the age of 30, many of whom migrate from rural areas or from abroad for a first formal sector job. Supervisors, who are typically male, can use their position to sexually harass workers in their team. “Quid pro quo” sexual harassment was commonly reported in Cambodia, for example, where a job benefit is offered in exchange for sexual favours or a sexual relationship.

- Sexual harassment during commute: Women are also subject to sexual harassment or violence commuting to and from their jobs. A 2019 report by Fair Wear Foundation and Care International found that nearly half of 763 interviewed women working in Vietnam’s garment factories claimed to have experienced violence or harassment commuting to and from their jobs.

- Long working hours: The garment sector is characterized by long working hours, which places extra burden on women who serve as primary caregivers in their families and communities. In times where a quick turnaround is required for orders placed by clients, employees are under immense pressure to work longer hours. Often, these business pressures mean employees are subject to verbal and physical abuse to intimidate them to reach production targets.

- Vulnerabilities facing female refugees and migrant workers: Female refugees and migrant workers are particularly vulnerable to exploitative conditions and face few legal protections and little recourse for mistreatment. For example, Fair Wear Foundation’s guidance on Syrian refugees employed in Turkish garment factories found that although they are legally able to obtain a work permit, registration restrictions and complications in the application process result in illegal working arrangements. Such arrangements put undocumented female migrant workers at particular risk of being subjected to excessive workings hours and/or wages below the legal minimum wage. The highly vulnerable status of female migrant workers also puts them at a higher risk of gender-based violence and sexual exploitation at work.

- Leadership representation: Although most workers in the apparel manufacturing industry are female, women remain vastly under-represented in senior-level management or leadership positions. A PwC report found that only 12.5% of apparel and retail companies in the Fortune 1000 are led by women. The report states that key factors impeding female leadership include a lack of CEO championship, institutional blind spots serving to maintain a traditionally male-dominated status quo and the lack of a structure within the industry supportive of women leaders.

Helpful Resources

- OECD, Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains in the Garment & Footwear Sector: This guidance aims to help fashion and apparel businesses implement the due diligence recommendations contained in the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises in order to avoid and address the potential negative impacts of their activities and supply chains on a range of human rights, including gender discrimination.

- ILO-IFC, Gender Equality in the Global Garment Industry: This resource identifies challenges to gender equality in factories participating in the Better Work programme, set up by the ILO and IFC. Companies may use this resource in identifying where they can intervene to improve gender equality in their garment manufacturing supply chain.

- ILO-IFC, Sexual Harassment at Work: Insights from the Global Garment Industry: This brief addresses the underlying conditions that lead to sexual harassment. Companies may use this guidance for ideas on implementing programmes to combat sexual harassment in garment factories.

- BSR, Empowering Female Workers in the Apparel Industry: Three Areas for Business Action: This resource proposes three areas where apparel companies should invest to drive improvements in outcomes for women workers and promote women’s economic empowerment around the world.

- Fair Wear Foundation and ILO International Training Centre, Ending Gender-based Violence: The apparel industry-focused NGO provides specific case studies, modules, reports and guidance on ending gender-based discrimination.

- BetterWork, Gender Equality in the Global Garment Industry: BetterWork’s 2018 — 2022 Strategy aims to promote women’s economic empowerment through targeted initiatives in apparel factories, and by strengthening policies and practices at the national, regional and international levels.

- Business for Social Responsibility, HERproject: BSR’s HERproject provides briefs, toolkits and guidance on women workers in the apparel and garment manufacturing sectors.

Information, Communications and Technology (ICT)

Globally, women remain significantly under-represented in high-growth, high-impact STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) roles, making up only 22% of artificial intelligence (AI) professionals globally. Within the technology industry, women represent only 34.4% of the workforce in the five largest tech companies in the world. According to the National Center for Women in Technology (NCWIT), in 2020, only 25% of the computing workforce in the US were female. This number declined even further for African-American (3%), Asian (7%) and Hispanic (2%) women.

Risk factors specific to the tech sector are as follows:

- Sociocultural gender bias: Sociocultural gender bias perpetuates the gender gap in the tech sector. On average, across OECD countries, only 0.5% of girls express a desire to become ICT professionals, compared to 5% of boys. This is reflected in the lower proportions of women graduating in ICTs, with only 25% female ICT graduates in 2015. Despite an industry-wide push, the proportion of women employed in the tech sector remains unchanged. Women entering the ICT sector, therefore, face a male-dominated workplace and barriers to their career development from the start.

- Gender discrimination: A predominantly male work environment in tech is one of the key drivers of gender discrimination. A lack of mentors and female role models, gender bias in the workplace, unequal pay for the same skills and unequal growth opportunities compared to men are among the most significant barriers experienced by women in tech. A 2020 ISACA report found that 22% of women surveyed felt underpaid relative to co-workers, as compared to 14% of men who were posed the same question.

- Sexual harassment across company ranks: High-profile cases of sexual harassment and gender discrimination in tech companies underscore the widespread risks to women in the sector. Harassment runs throughout company ranks, with a 2020 survey by Women Who Tech finding that 44% of women founders have experienced harassment. The survey also found that women of colour were harassed more by investors, with 46% facing harassment as compared to 38% of white women.

- Entrepreneurship gender gap: The gender gap in entrepreneurship is another key example of discrimination against women. Women-owned tech start-ups receive 23% less funding and are 30% less likely to be acquired or to issue an initial public offering compared to men-owned businesses. Inherent biases, such as perceptions among investors of women over a certain age wanting to begin a family life, drive discriminatory attitudes towards female tech founders.

- COVID-19 pandemic: The COVID-19 pandemic has also severely impacted the career progression of women in the tech sector. A 2021 Kaspersky report stated that while some women appreciated the greater flexibility of work-from-home arrangements due to the pandemic, others were on the verge of burnout. Working remotely can be a challenge for women as they experience less access to top management than when working from offices, which may decrease their chances to be considered for stretch assignments that lead to promotions.

- Career progression: This further compounds gender discrimination trends prior to pandemic. A 2021 TrustRadius report found that 78% of women felt they had to work harder than their male co-workers to prove their worth. The report also found that women of colour were even less confident than white women about their prospects for promotion, with 37% reporting racial bias as a barrier to promotion.

Helpful Resources

- OECD, Bridging the Digital Gender Divide: Include, Upskill, Innovate: This report provides policy directions for consideration by all Governments, including G20 economies’ Governments through identifying, discussing and analyzing a range of drivers at the root of the digital gender divide.

- UNESCO, Women and the Digital Revolution: This resource provides statistics on women in STEM sectors.

- TrustRadius, 2021 Women in Tech Report: This report looks at key trends arising out of the past year of women in tech, and the biggest challenges they face, particularly throughout the pandemic period.

- Kaspersky, Women in Tech Report: Where Are We Now? Understanding the Evolution of Women in Technology: This report explores how women perceive the tech industry, the opportunities available to them and the barriers still presenting challenges.

- PwC, Women in Tech: Time to Close the Gender Gap: This report includes a call to action that features four actions the tech sector can take to boost the number of women working in technology.

- Women Who Tech, The State of Women in Tech and Startups: Top Findings for 2020: This resource provides poll findings of 1,003 tech employees, founders and investors surveyed on their experiences in the tech sector.

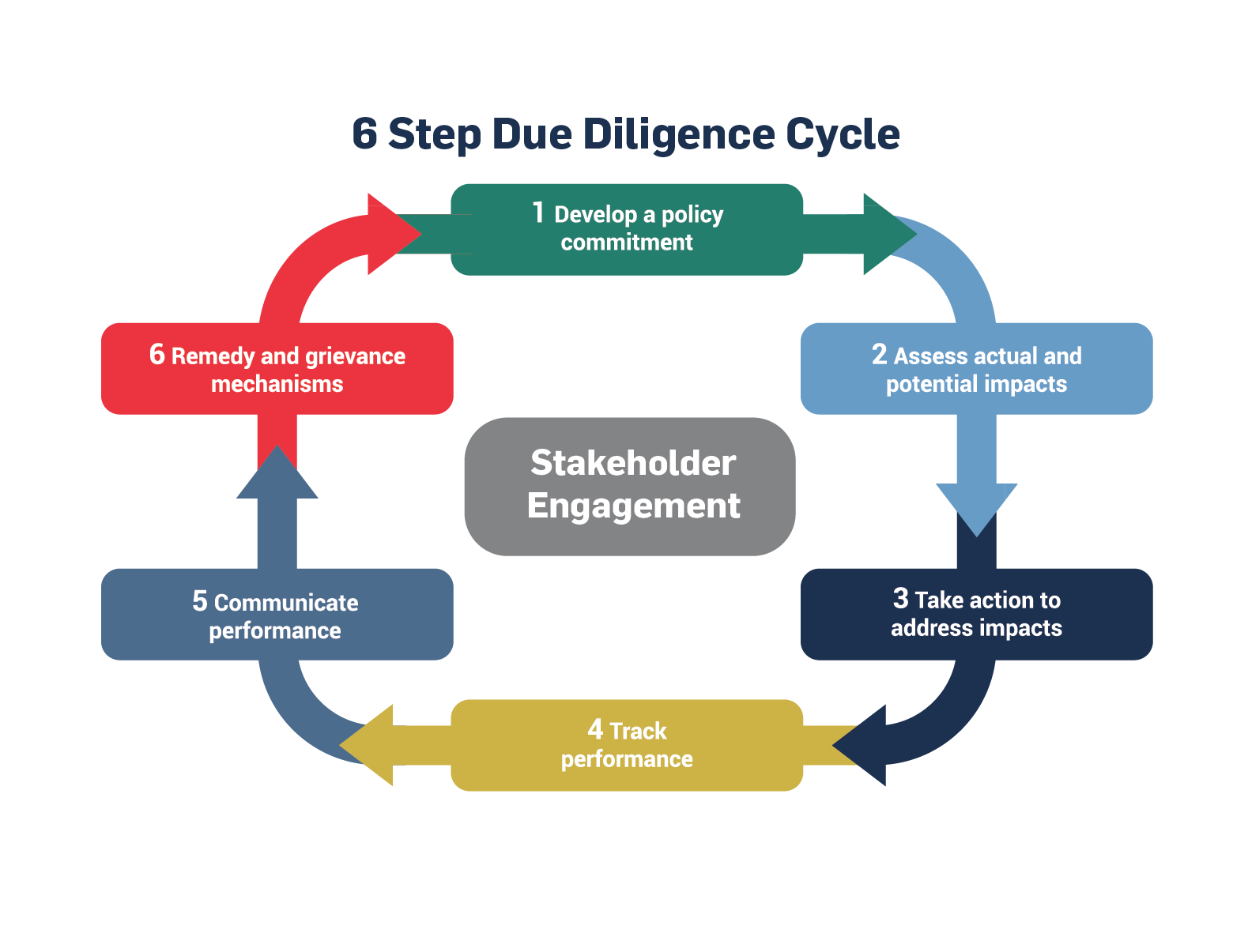

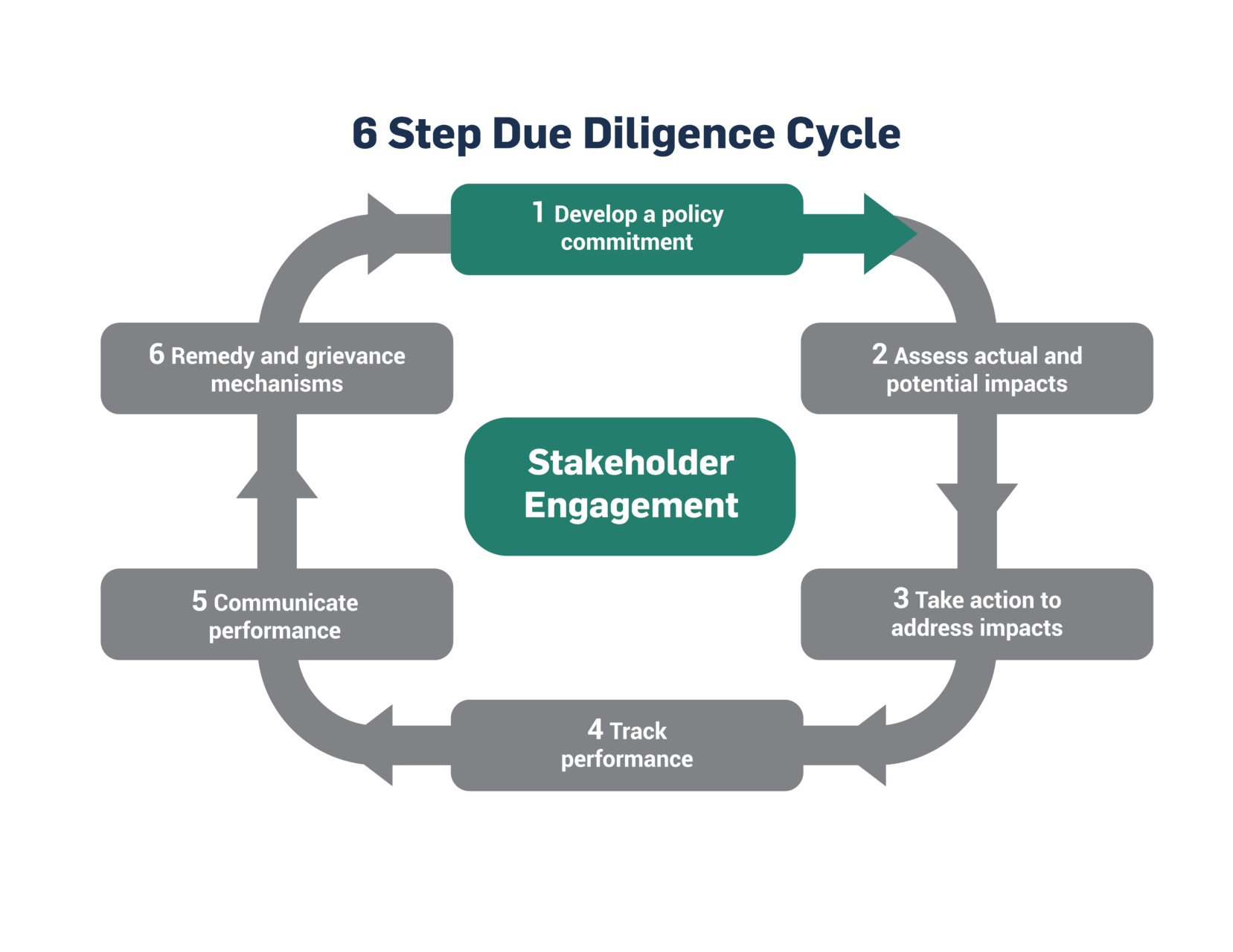

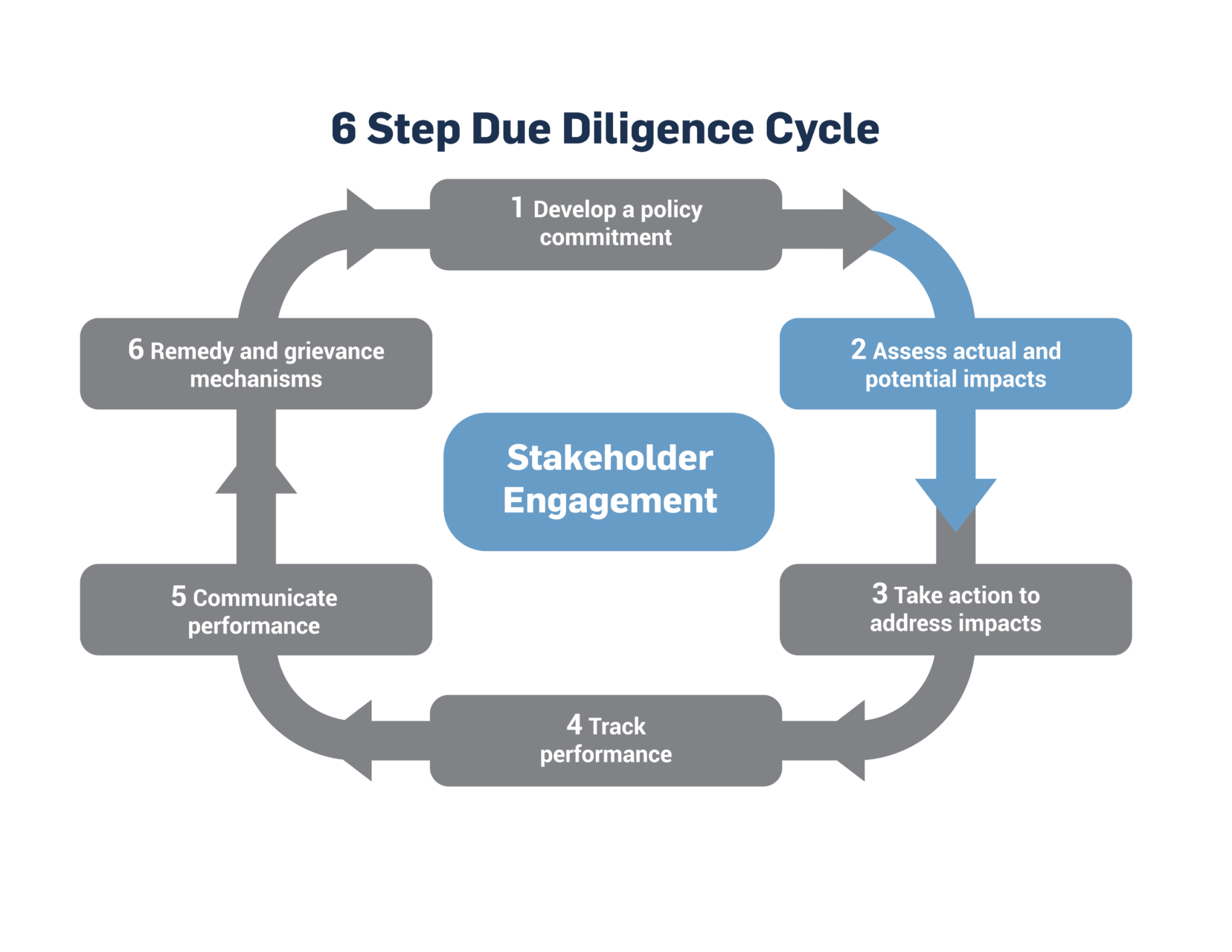

Due Diligence Considerations

This section outlines due diligence steps that companies can take to promote gender equality in their operations and supply chains. At a minimum, business has the responsibility to respect the rights of women and girls, such as by putting in place non-discrimination and sexual harassment policies. In addition, companies can create inclusive business models and invest in women’s economic empowerment programmes. They can also partner with organizations to advance women’s rights and advocate for gender equality policies. Such actions to support women’s rights should be a complement, not a substitute for respecting women’s rights.

The described due diligence steps are aligned with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in June 2011, the UNGPs provide an authoritative global standard for preventing and addressing the risk of adverse impacts on human rights linked to business activity. The UNGPs emphasize that women and girls experience business-related human rights abuses in unique ways and are often affected disproportionately. In a nutshell, business has a responsibility to respect human rights by avoiding any infringement of the human rights of others, including women, and addressing any adverse human rights impact with which the business is involved. Further information on UNGPs is provided in the ‘Key Human Rights Due Diligence Frameworks’ section below or in the Introduction.

Key Human Rights Due Diligence Frameworks

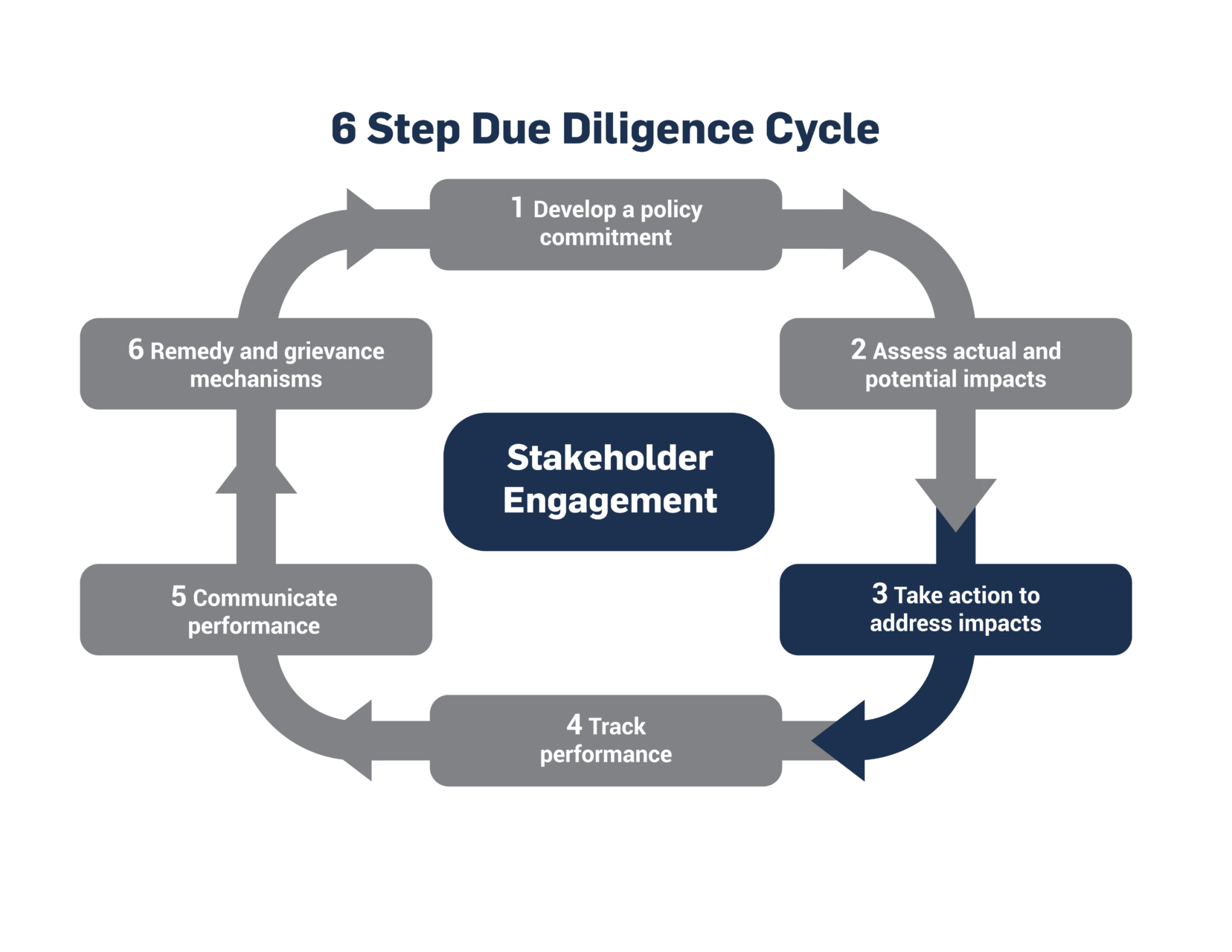

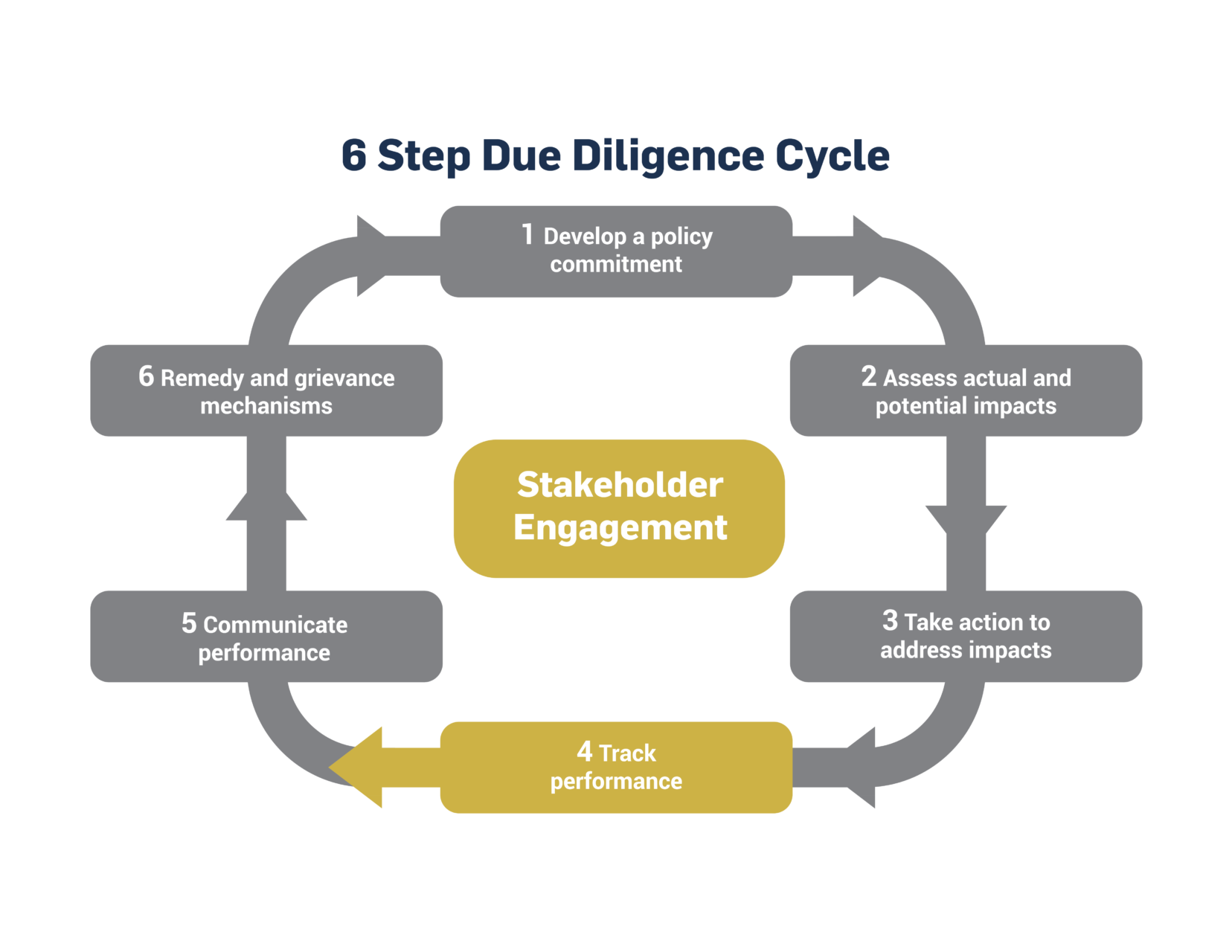

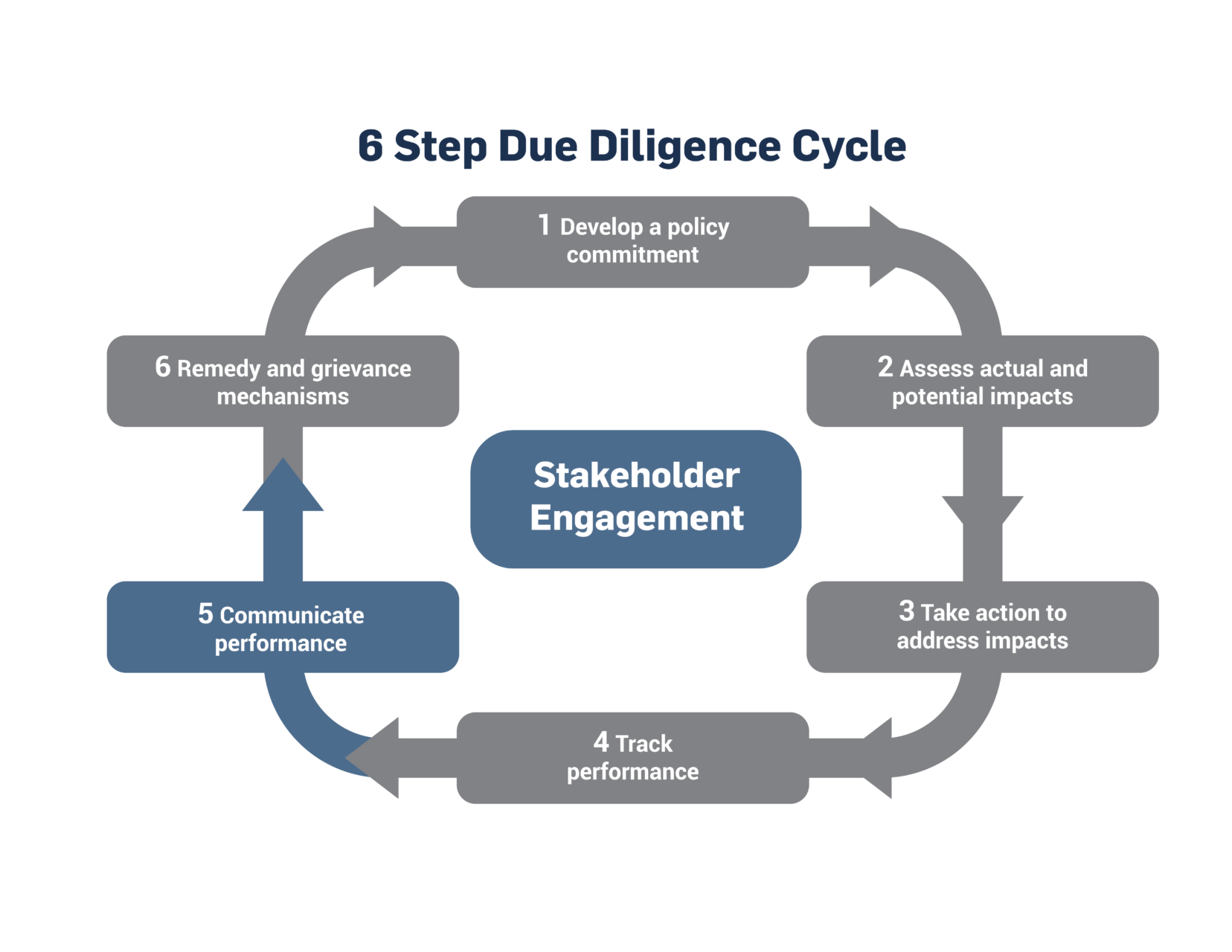

Several human rights frameworks describe the due diligence steps that businesses should ideally implement to address human rights issues, including gender equality. The primary framework is the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). Launched in 2011, the UNGPs offer guidance on how to implement the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework, which establishes the respective responsibilities of Governments and businesses — and where they intersect.

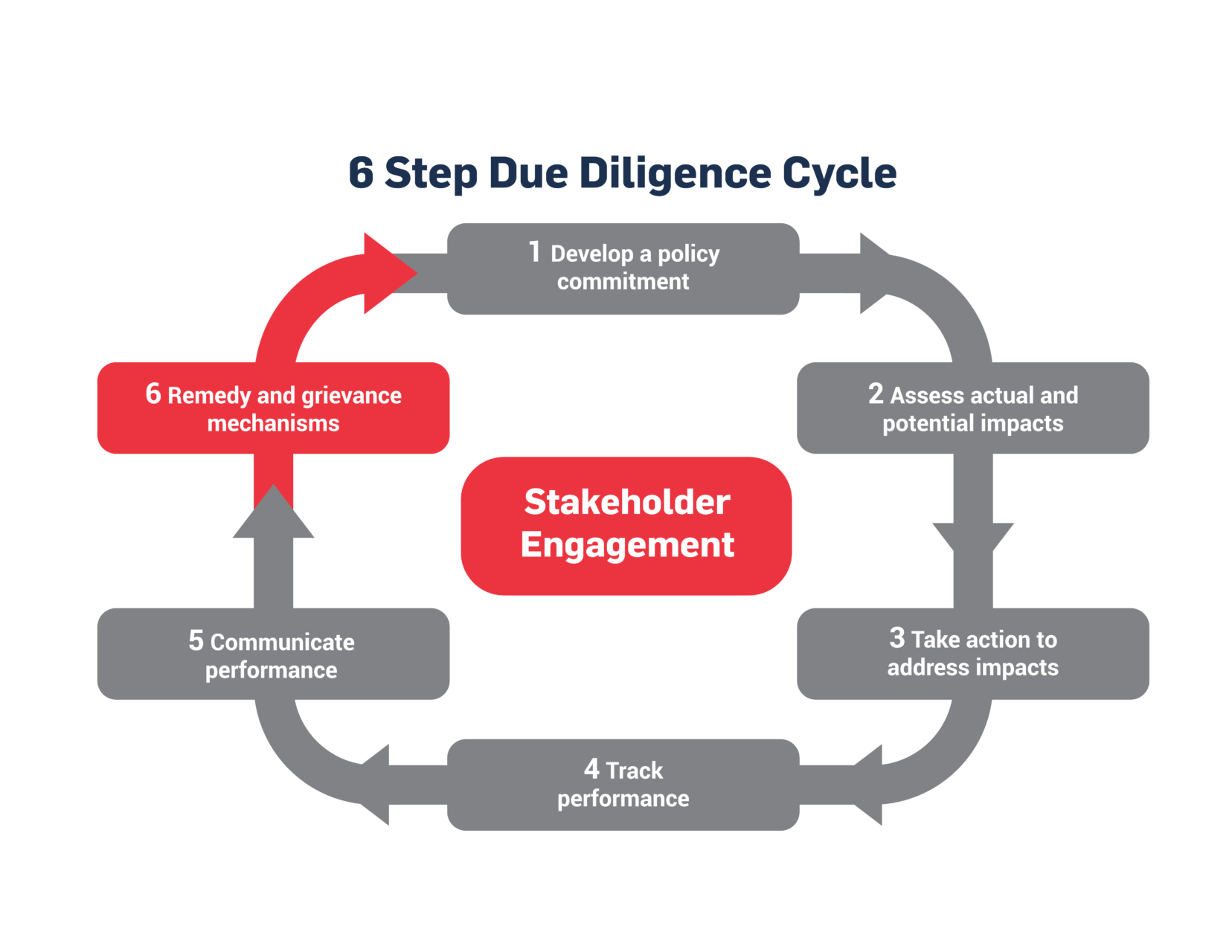

The UNGPs set out how companies, in meeting their responsibility to respect human rights, should put in place due diligence and other related policies and processes, which include:

- A publicly available policy setting out the company’s commitment to respect human rights;

- Assessment of any actual or potential adverse human rights impacts with which the company may be involved across its entire value chain;

- Integration of the findings from their impact assessments into relevant internal functions/processes — and the taking of effective action to manage the same;

- Tracking of the effectiveness of the company’s management actions;

- Reporting on how the company is addressing its actual or potential adverse impacts; and

- Remediation of adverse impacts that the company has caused or contributed to.

The steps outlined below follow the UNGPs framework and can be considered a process which a business looking to start implementing human rights due diligence processes can follow.

Additionally, the OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises define the elements of responsible business conduct, including human and labour rights.

Another important reference document is the ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy (MNE Declaration), which contains the most detailed guidance on due diligence as it pertains to labour rights. These instruments, articulating principles of responsible business conduct, draw on international standards enjoying widespread consensus.

While the below steps provide guidance on gender equality in particular, it is important — and more resource-efficient — for companies to integrate gender equality into due diligence processes focusing on other human rights issues (e.g. applying a “gender lens” to child labour or forced labour).

Human Rights Due Diligence Through a Gender Lens

Companies can seek specific guidance on gender equality and other issues relating to international labour standards from the ILO Helpdesk for Business. The ILO Helpdesk assists company managers and workers that want to align their policies and practices with principles of international labour standards and build good industrial relations. It has a specific section on non-discrimination and equality. The WEPs Secretariat also offers support, guidance and capacity building to help companies fully implement the WEPs.

Additionally, the SME Compass offers guidance on the overall human rights due diligence process by taking businesses through five key due diligence phases. The SME Compass has been developed in particular to address the needs of SMEs but is freely available and can be used by other companies as well. The tool, available in English and German, is a joint project by the German Government’s Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

1. Develop a Policy Commitment on Gender Equality

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, a human rights policy should be:

- “Approved at the most senior level” of the company;

- “Informed by relevant internal and/or external expertise”;

- Specific about company’s “human rights expectations of personnel, business partners and other parties directly linked to its operations, products or services”;

- “Publicly available and communicated internally and externally to all personnel, business partners and other relevant parties”; and

- “Reflected in operational policies and procedures necessary to embed it throughout the business”.

A logical starting point for any business to tackle gender discrimination is to develop a company commitment to gender equality. For example, the European telecommunications company Vodafone and the South African mining company AngloGold Ashanti both have stand-alone gender equality policies. The integration of women’s rights into a human rights policy is another option that companies such as H&M have adopted. Where companies do not have a human rights policy, gender equality is often addressed in other documentation, such as a business code of conduct or ethics and/or a supplier code of conduct.

Companies can demonstrate their policy commitment on gender equality and its implementation in day-to-day activities by joining the WEPs platform. By joining the WEPs community, the CEO signals commitment to the gender equality agenda at the highest levels of the company.

Businesses may also consider aligning their gender equality policies with relevant industry-wide or cross-industry policy commitments, for example:

- Responsible Business Alliance (RBA) Code of Conduct

- Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI) Base Code

- amfori BSCI Code of Conduct

- Fair Labor Association (FLA) Code of Conduct

- EDGE Gender & Intersectional Equity Certification

Helpful Resources

- Women’s Empowerment Principles, Equality Means Business: This is a toolkit for WEPs Signatories at all stages of the WEPs journey, from companies first learning about the WEPs to current Signatories looking to advance their work on gender equality and women’s empowerment. This platform also provides policy templates for businesses (e.g. Domestic Violence Policy, Gender-Based Violence and Harassment at Work Policy, Flexible Work Policy Template, etc.).

- BSR, Gender Equality in Codes of Conduct Guidance: BSR has developed a guidance that makes recommendations on how companies can strengthen their clauses to promote gender equality in the workplace, with a specific focus on developing and emerging markets-based supply chains.

- ILO, Gender Diversity Journey: Company Good Practices: This guidance was developed to share the experience of companies in attracting and retaining female talent, including ideas on how to establish an equal employment opportunity policy.

- ILO-UN Women, Empowering Women at Work: Company Policies and Practices for Gender Equality: This resource presents key guiding frameworks and examples for companies to develop gender equality policies.

- ICoCA, Guidelines for Private Security Providers on Preventing and Addressing Sexual Exploitation and Abuse: These guidelines are designed to help private security companies write Codes of Conduct to effectively prevent and address sexual exploitation.

- The B Team, Gender Balance and Inclusive Cultures: A Guide for CEOs: This guide was developed to help CEOs improve corporate culture, support their employees and make their business more secure and profitable in the long-term by fostering greater diversity and inclusion.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Base Code Guidance: Gender Equality (B) — Gender and Human Rights Due Diligence: A detailed guide on human rights due diligence on gender equality, including a section on building company leadership and commitment to gender equality and women’s rights.

- Women Win, Gender-Responsive Due Diligence (GRDD) Platform: This online platform describes the process of adding a gender lens to human rights due diligence, including Step 1 (“Embed in Policies”).

- Girls Advocacy Alliance, A Gender-responsive Human Rights Due Diligence Tool: Organized around the six steps of human rights due diligence, this toolkit offers a conceptual framework, as well as practical guidance for planning, implementing and monitoring Gender-responsive Human Rights Due Diligence (GR-HRDD) processes, including Step 1 “Embed gender equality into your policies & management systems”.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to develop a human rights strategy and formulate a policy statement.

- SME Compass, Policy statement: Companies can use this practical guide to learn to develop a policy statement step-by-step. Several use cases illustrate how to implement the requirements.

- United Nations Global Compact, Advancing decent work in business Learning Plan: This learning plan, helps companies understand each Labour Principle and its related concepts and best practices as well as practical steps to help companies understand and take action across a variety of issues.

- United Nations Global Compact-OHCHR, A Guide for Business: How to Develop a Human Rights Policy: This guidance provides recommendations on how to develop a human rights policy and includes extracts from companies’ policies referencing non-discrimination.

2. Assess Gender Equality Impacts

UNGP Requirements

The UNGPs note that impact assessments:

- Will vary in complexity depending on “the size of the business enterprise, the risk of severe human rights impacts, and the nature and context of its operations”;

- Should cover impacts that the company may “cause or contribute to through its own activities, or which may be directly linked to its operations, products or services by its business relationships”;

- Should involve “meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups and other relevant stakeholders” in addition to other sources of information such as audits; and

- Should be ongoing.

Impact assessments should look at both actual and potential impacts, i.e. impacts that have already manifested or could manifest. This compares to risk assessments that would only look at potential impacts and may not satisfy all of the above criteria.

Impact assessments look at existing impacts from business practices, potential impacts that companies can anticipate, the likelihood of these impacts occurring and the severity of both actual and potential impacts. The scope of impact assessments should include not only gender equality issues in the workplace but also potential and actual impacts on gender equality in supply chains and in communities of operation.

A wide range of stakeholders, including suppliers and civil society, should be involved in the identification and assessment of gender equality impacts. Consulting experts with experience of working with vulnerable groups and collecting data on sensitive issues such as sexual and reproductive health, and violence against women and girls, may also be helpful for businesses to uncover gender-specific risks that may be hidden due to prevailing gender norms and inequality. To gain deeper insights, it is necessary to talk with (female) stakeholders directly outside the presence of men. Where access to female informants is limited (e.g. at the lower levels of the supply chain), secondary information can be gathered from trade union representatives, industry associations, local women’s organizations and community representatives.

To collect data for impact assessments companies should consider analyzing the following:

- Activities, geographies or products where gender inequality risks are most likely to be present: Country-level information on gender equality may be helpful in identifying potential issues in countries of operation and supply, as well as in key consumer markets. This may include countries with severe gender-discrimination due to existing norms, conflict and post-conflict zones, sectors employing large numbers of women or products that potentially exclude women as customers. A guide on Gender Responsive Due Diligence in Supply Chains by BSR includes a list of global country-level gender indices.

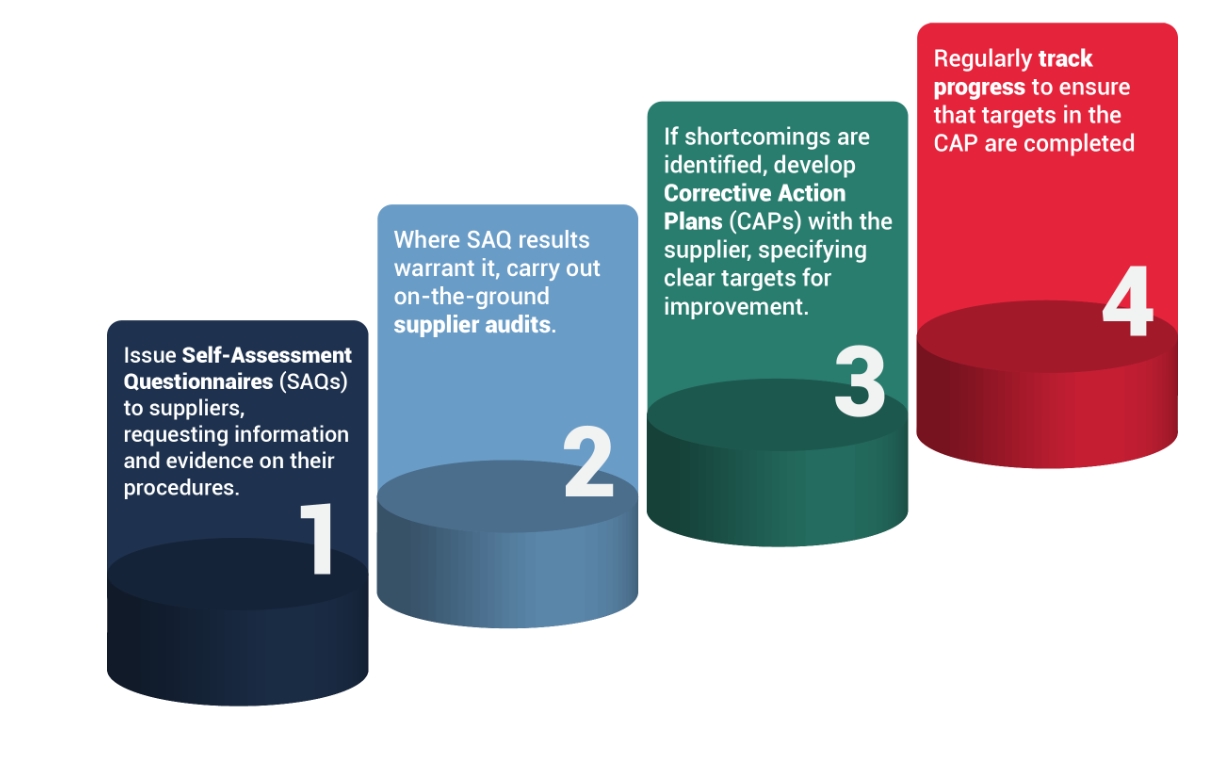

- Sex-disaggregated data on workforce in company operations and supply chains, including the number of employees and board directors, percentage of managers/supervisors, percentage of pregnancy/maternity leave versus total time available, percentage of home workers vs. on-site workers, etc. A Gender-responsive Human Rights Due Diligence Toolby Girls Advocacy Alliance provides a helpful list of indicators on workforce profile, workforce performance and worker impact that could be analyzed as part of data collection process. Collecting supplier sex-disaggregated workforce data is more difficult but could be achieved through suppliers self-assessment questionnaires or audits.

- Existing policies and procedures that may be undermining women’s rights: This should include both internal policies and procedures and those with suppliers and local communities. For example, companies’ buying practices may cause or contribute to suppliers’ unethical practices, which in turn may impact the working conditions of female workers. External communication, advertising and marketing should also be included in the scope of policy and procedural review.

- External risks from events outside the company and beyond its control. For example, natural disasters often affect women and men differently due to gender inequalities caused by socio-economic conditions and cultural beliefs. The COVID-19 pandemic offers another example of external risks outside of company control with significant impacts on women who were not only the main caretakers of the sick during the pandemic, but also were in the lowest paid jobs and therefore most vulnerable to layoffs.

Once a list of potential and actual impacts is compiled, companies should assess and prioritize them by evaluating their likelihood and severity. The following considerations should be made:

- Assessing the likelihood and severity of each identified impact specifically for women: For example, women are significantly more likely to experience sexual harassment than men. Likewise, persistent overtime tends to have a bigger impact on women than on men due to women’s household and childcare responsibilities before and after work.

- Differentiating impacts on different groups of women: Women from ethnic minorities may face a greater or different type of discrimination. Young women may face more harassment than older women. Pregnant women and mothers may have a higher chance of losing their jobs and fewer opportunities to join the workforce at a later stage.

To help companies conduct gender equality impact assessments, the UN Global Compact, in partnership with UN Women, the Multilateral Investment Fund of the Inter-American Development Bank and IDB Invest, developed the WEPs Gender Gap Analysis Tool. The WEPs Tool is designed to help companies assess current policies and programmes, identify areas for improvement and consider opportunities to set future corporate goals and targets. The WEPs Tool comprises 18 multiple choice questions that draw from global best practices and cover topics such as commitment to a gender equality strategy, equal pay, recruitment, supporting parents and caregivers, women’s health, inclusive sourcing and advocacy for gender equality in communities of operation.

Helpful Resources

- Women Win, Gender-Responsive Due Diligence (GRDD) Platform: This online platform describes the process of adding a gender lens to human rights due diligence, including Step 2 (“Identify and assess adverse impacts”).

- Girls Advocacy Alliance, A Gender-responsive Human Rights Due Diligence Tool: Organized around the six steps of human rights due diligence, this toolkit offers a conceptual framework, as well as practical guidance for planning, implementing and monitoring Gender-responsive Human Rights Due Diligence (GR-HRDD) processes, including Step 2 “Identify & assess gender risks & adverse impacts”).

- BSR, Making Women Workers Count: A Framework for Conducting Gender Responsive Due Diligence in Supply Chains: This report helps both brands and suppliers conduct better and more effective gender-responsive due diligence. Provides recommendations along four phases of due diligence, including Phase 1 (Assess and Analyze).

- WECF International, The Gender Impact Assessment and Monitoring Tool: This tool has been developed in the framework of the Women2030 programme, with the objective of providing Women2030 partners with a common understanding of how to assess gender issues within local, regional and national contexts.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Base Code Guidance: Gender Equality (B) — Gender and Human Rights Due Diligence: A detailed guide on human rights due diligence on gender equality, including ‘Assessment and Analysis’ section that provides guidance on a graduated approach to gender assessments.

- ILO, Maternity and Paternity at Work: Law and Practice across the World: The study reviews national law and practice on both maternity and paternity at work in 185 countries and territories including leave, benefits, employment protection, health protection, breastfeeding arrangements at work and childcare.

- ILO, Labour Statistics on Women: ILOSTAT contains a wide range of indicators disaggregated by sex, as well as breakdowns relevant to gender issues and indicators on gender gaps.

- Arizona State University, Global SDG 5 Notification Tool: This tool provides insight into country-level progress towards eliminating discriminatory laws around the world.

- The World Bank, Women, Business and the Law: This report analyzes laws and regulations affecting women’s economic inclusion in 190 economies.

- UN Women, COVID-19 and Gender Rapid Self-Assessment Tool: Building on the seven WEPs, this tool enables companies to assess their COVID-19 response and ensure they are supporting women during and beyond the crisis with gender-sensitive measures throughout their value chain.

- World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Report 2022: A report on gender parity that provides rankings for 146 countries on gender gaps in four areas: Economic Participation and Opportunity, Educational Attainment, Health and Survival, and Political Empowerment. This report also includes detailed country profiles.

- Girl Stats: A resource that provides interactive data aligned with the SDGs, offering insight into key issues faced by adolescent girls and young women around the world.

- CSR Risk Check: A tool allowing companies to check which international CSR risks (including related to gender equality) businesses are exposed to and what can be done to manage them. The tool provides tailor-made information on the local human rights situation as well as environmental, social and governance issues. It allows users to filter by product/raw material and country of origin. The tool was developed by MVO Netherland; the German version is funded and implemented by the German Government’s Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights and UPJ.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to assess actual and potential human rights risks and how to assess and prioritize risks.

- SME Compass, Risk Analysis Tool: This tool helps companies to locate, asses and prioritize significant human rights and environmental risks long their value chains.

- SME Compass, Supplier review: This practical guide helps companies to find an approach to manage and review their suppliers with respect to human rights impacts.

3. Integrate and Take Action on Gender Equality Impacts

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, effective integration requires that:

- “Responsibility for addressing [human rights] impacts is assigned to the appropriate level and function within the business enterprise” (e.g. senior leadership, executive and board level);

- “Internal decision-making, budget allocations and oversight processes enable effective responses to such impacts”.

The WEPs platform provides a framework that companies can use to take action on gender equality in the workplace, marketplace and community. In addition, the UN Global Compact launched “Target Gender Equality”, an accelerator programme that uses the WEPs Gender Gap Analysis Tool to evaluate performance and identify risk areas, then puts principle into practice by guiding implementation and providing concrete steps towards achieving goals. The programme helps companies create more inclusive workplaces, break down barriers to equality and meet ambitious targets for women’s representation and leadership.

Some actionable steps towards gender parity in the workforce, marketplace and community include:

- Addressing working practices that indirectly disadvantage women: These include checking hiring and promotion practices for potential bias, introducing targets and quotas for female representation, achieving equal pay for work of equal value, etc. As part of these efforts, companies can consider delivering unconscious bias training for workers at all levels, but particularly for senior management.