Created in partnership with the Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights

Freedom of Association

The right of workers to associate freely can be compromised by legislative and practical barriers, including discrimination, intimidation and even violence.Overview

What is Freedom of Association?

Freedom of association entails respect for the right of employers and workers to freely and voluntarily establish and join organizations of their own choice, according to the International Labour Organization (ILO). These organizations have the right to carry out their activities in full freedom and without interference. Employers should not interfere in workers’ decisions to associate or discriminate against either those workers who choose to associate or those who act as their representatives. The Government should not interfere in the right of either workers or employers to form associations.

The right of workers to bargain freely with employers is an essential element in freedom of association. Collective bargaining is a voluntary process through which employers and workers discuss and negotiate their relations, in particular terms and conditions of work. It can involve employers directly (or as represented through their organizations) and trade unions or, in their absence, representatives freely designated by the workers. Although freedom of association and collective bargaining are significantly inter-connected, this issue focuses primarily on the right to freedom of association.

What is the Dilemma?

The dilemma for business is how to respect the right to freedom of association when its operations, business partners or suppliers are based in countries where such rights may be restricted in law and/or practice. Even if workers formally enjoy the right to freely associate, they can still face a range of practical barriers, including discrimination, informal restrictions, intimidation and even violence. If companies restrict workers’ rights to form or join a union or workers’ organization, it is likely that other rights are also impacted. This could result in labour rights violations, such as greater safety and health risks, discriminatory practices or the use of forced labour, leading to operational, financial and legal risks for companies.

Global Overview and Trends on Freedom of Association

In some countries workers are denied the right to associate, workers’ and employers’ organizations are illegally suspended or interfered with, and in some cases, trade unionists are arrested or killed. Companies face significant challenges in ensuring freedom of association in countries where such rights may not be recognized in law or practice.

According to the ILO, unions play a key role in the quest to achieve better remuneration and working conditions. Union membership combined with unions’ bargaining power has a significant impact on workers’ conditions and directly impact stability, labour market governance and the economy as a whole. The latest available OECD data suggests that the average degree of trade union density — the proportion of paid workers who are union members — in OECD countries in 2019 was around 16%. There is a substantial variation between OECD countries, some of which are highly unionized, such as Denmark (66.5%) and Sweden (64.9%), and others that have much lower unionization rates, such as the United States (10.1%). In some countries, such as France, union density is low (8.8%) but the social dialogue mechanisms at the sectoral and national level are strong with a positive impact on the protection of workers’ rights. A 2022 flagship ILO report on social dialogue found that collective bargaining can make an important contribution to the inclusive and effective governance of work, with positive effects on stability, equality, compliance and the resilience of enterprises and labour markets.

Key trends include:

- The ILO reports that unionization was severely affected by lockdowns and restrictive measures due to COVID-19. While unions generally welcomed their Governments’ COVID-19 responses, in many instances they expressed their dissatisfaction with the implementation of social dialogue mechanisms and the lack of trade union participation in decision-making processes.

- The ILO reports that in many advanced countries, a decline in trade union membership has eroded the quality of collective bargaining agreements and weakened the bargaining power of workers.

- According to the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), there was an increase in the number of countries that impeded the registration of unions, from 59% of countries in 2014 to 79% in 2022. In 2022, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) continued to be the world’s worst region for unions, with continued dismantling of independent unions and prosecuting and sentencing of workers participating in strikes. The ITUC finds that the ten worst countries for working people in 2021 are Bangladesh, Belarus, Brazil, Colombia, Egypt, Eswatini, Guatemala, Myanmar, The Philippines and Turkey.

- In 2021, the ITUC also identified a new trend of increasing levels of surveillance by Governments and companies of individuals, which is an ever-growing threat to human and labour rights. Some Governments continue their surveillance of prominent trade union leaders to instill fear and put pressure on independent unions and their members. Several scandals emerged in 2021 over surveillance instigated by companies to track and frustrate union organizing efforts and strike actions.

- Migrant workers in the Gulf are particularly at risk of violations of the right to freedom of association as they are often excluded from labour protections. In addition, labour activists in these countries may also experience State repression. The ILO notes that most violations of trade unions’ rights during the COVID-19 crisis were reported to take place predominantly in the Arab States.

- According to the ILO, an increasing trend of casualization of the global workforce has had negative impacts on freedom of association. Casualization refers to a shift from full-time and permanent jobs to casual and contract positions that typically lack social protections and employment security. Workers in the informal sector, agency and self-employed workers typically face challenges in securing freedom of association rights.

- Additionally, a 2022 ILO report found that collective bargaining played a role in mitigating adverse economic and other impacts on workers that arose out of the COVID-19 crisis. Collective agreements provided protection for many workers and supported the continuity of economic activity during the pandemic.

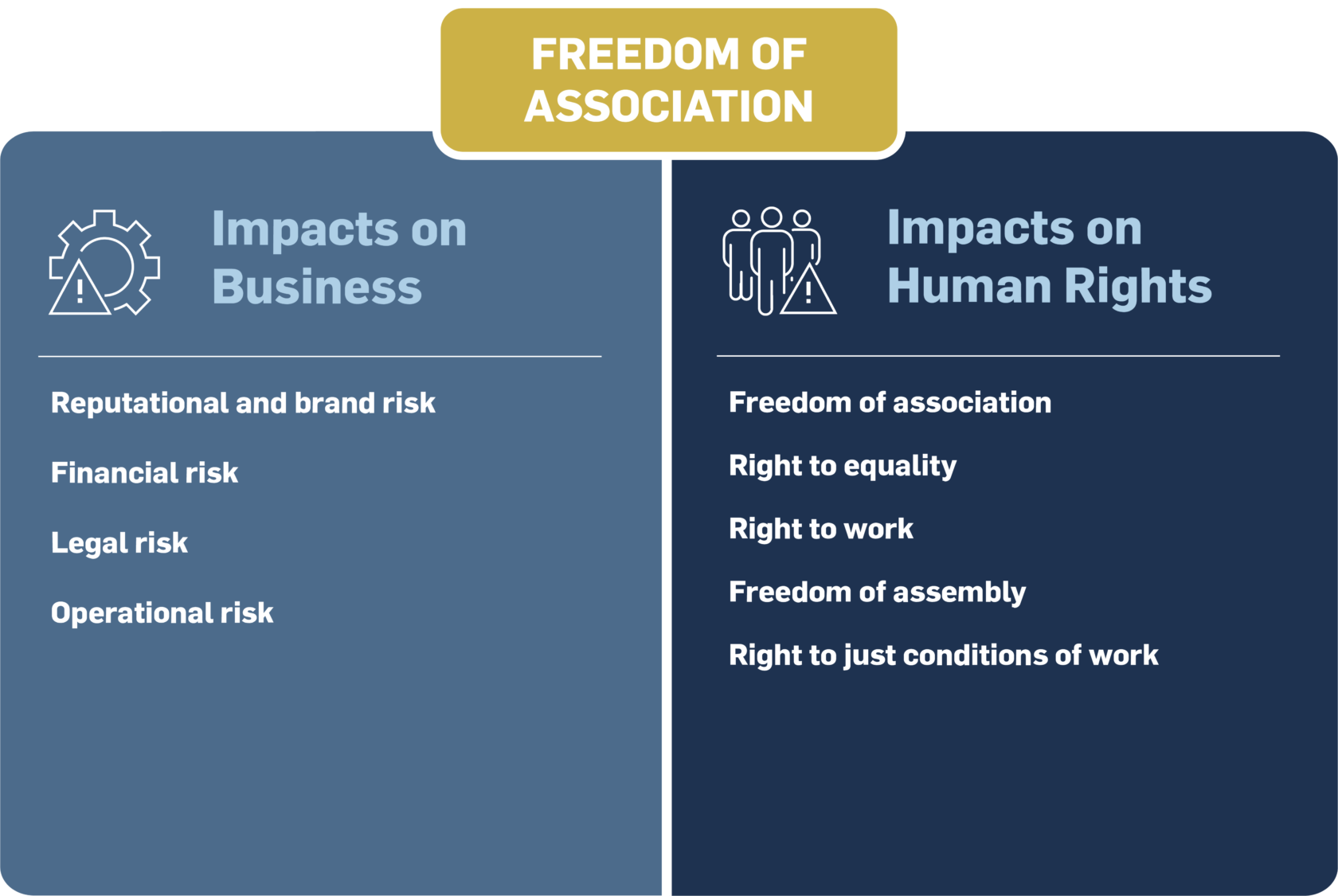

Impacts on Businesses

Businesses can be impacted by restrictions to freedom of association in their operations and supply chains in multiple ways:

- Reputational and brand risk: With increasing public awareness and scrutiny of business operations, companies that fail to fulfil their responsibilities concerning the right to freedom of association incur a substantial reputational risk. Activist campaigns by civil society groups, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and global unions have been successful at calling attention to reported restrictions to freedom of association by employers. This often results in damage to the brand and the company’s reputation.

- Financial risk: Scrutiny arising out of activist campaigns or negative press coverage of companies found to restrict workers’ or trade unions’ rights can impact consumer demand and result in loss of sales. Divestment and/or avoidance by investors and finance providers (many of which are increasingly applying environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria to their decision-making) may result in reduced or more expensive access to capital.

- Legal risk: Companies operating in countries where the right to freedom of association is enshrined in national law may face legal risks if they are found to obstruct union activity or workers’ rights. Particularly in cases where union groups or workers are well organized and are prepared to resort to litigation, companies face exacerbated legal risks if linked to freedom of association violations.

- Operational risk: A failure to provide legitimate channels through which workers can articulate grievances and concerns can result in a breakdown in communications and acrimonious disputes impacting management and company productivity. High levels of employee turnover, resulting from existing grievances being unaddressed, can also undermine company productivity.

Several internal business reasons underpin why companies should support and encourage the realization of rights to freedom of association in their operations and in their supply chains. At the individual company level, respect for the right of workers to organize and good industrial relations in the workplace help to facilitate the development of social capital that enhances employee engagement and staff retention, thereby increasing productivity and performance.

Impacts on Human Rights

Restrictions to the right to freedom of association have the potential to impact on a range of human rights,[1] including but not limited to:

- Right to freedom of association (UDHR, Article 20; ICCPR, Article 22; ICESCR, Article 8): The right to freedom of association is a human right in and of itself. This includes the right to form and join trade unions for the protection of their interests as well as to participate in activities.

- Right to equality before the law, equal protection of the law and right of non-discrimination (UDHR, Article 2; ICCPR, Article 26): Trade unions pool workers’ resources, which can be used to defend their legal rights more effectively than each worker trying to bring a case on his or her own. Trade union activists can experience discrimination in the form of arbitrary dismissal, demotion or lack of access to promotions.

- Right to work (UDHR, Article 23; ICESCR, Article 6): The right to work includes a prohibition of arbitrary dismissal. However, trade union members in many countries are arbitrarily dismissed by employers because of trade union membership or collective bargaining activities. Trade union representatives can support workers in contesting a wrongful dismissal.

- Right to freedom of assembly (UDHR, Article 20; ICCPR, Article 21): The right enables workers and trade union members to peacefully undertake group demonstrations. In many countries, army, police or company security may interfere in workers’ exercise of their right to demonstrate, which in extreme circumstances may end in violence.

- Right to enjoy just and favourable conditions of work (UDHR, Article 23; ICESCR, Article 7): The right to enjoy just and favourable conditions at work includes a wage that enables families to enjoy the right to a decent standard of living and for parents to maintain reasonable working hours. In many countries where trade unions are not independent or present, these conditions are often not met.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The following SDG targets relate to freedom of association:

- Goal 8 (“Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all”), Target 8.8: Protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments of all workers, including migrant workers, particularly women migrants, and those in precarious employment. Indicator 8.8.2 specifically pertains to freedom of association.

- Goal 16 (“Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels”):

- Target 16.3: Promote the rule of law at the national and international levels, and ensure equal access to justice for all;

- Target 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels; and

- Target 16.10: Ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms, in accordance with national legislation and international agreements.

- Goal 5 (“Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”), Target 5.5: Ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic, and public life.

Key Resources

The following resources provide further information on how businesses can uphold freedom of association in their operations and supply chains:

- ILO, Freedom of Association and Development: This resource provides ideas for employers’ organizations on how to work together with trade unions, Governments and other relevant stakeholders to achieve sustainable development.

- ILO, Social Dialogue Report 2022: Collective bargaining for an inclusive, sustainable and resilient recovery: This report looks at the role of collective bargaining in mitigating adverse economic impact on employment and earnings, and highlights the need for freedom of association for a resilient, inclusive and sustainable recovery.

- ITUC, Global Rights Index 2023: Companies can use this resource to assess the risks to freedom of association globally and to identify the highest risk countries and regions. This report looks at specific themes in relation to workers’ rights, such as the right to strike, collective bargaining and access to justice, which enables companies to identify which issues are most pertinent to their country of operation.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Freedom of Association in Company Supply Chains: This guide provides practical help to companies in identifying and understanding the impacts of their operations on freedom of association. It provides suggestions on how companies can drive change in their supply chains in terms of monitoring and protecting these rights.

- DCAF, ICRC, GBHR, Security and Human Rights Toolkit: This fact sheet provides practical guidance for human rights defenders in ensuring effective security and human rights.

- OHCHR, About human rights defenders: This page explains who human rights defenders are and the challenges they face.

Definition & Legal Instruments

Definition

According to the ILO, the term “Freedom of Association” refers to the right of workers and employers to freely and voluntarily establish and join organizations of their own choice. Freedom of association is a fundamental human right proclaimed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and is important as:

- It is the enabling right to allow effective participation of non-State actors in economic and social policy, central to democracy and the rule of law. Ensuring that workers and employers have a voice and are represented is, therefore, essential for the effective functioning of not only labour markets but also overall governance structures in a country.

- The right of workers and employers to form and join organizations of their own choosing is an integral part of a free and open society. In many cases, these organizations have played a significant role in their countries’ democratic transformation.

Workers form unions so that they can engage in collective bargaining. The ILO defines collective bargaining as a voluntary process through which employers and workers discuss and negotiate their relations, in particular terms and conditions of work. Participants include employers themselves or their organizations, and trade unions or, in their absence, representatives freely designated by the workers.

- The ILO states that collective bargaining allows both sides to negotiate a fair employment relationship and prevents costly labour disputes. Typical issues on the bargaining agenda include wages, working time, training, occupational safety and health, as well as equal treatment.

- According to the ILO, countries with highly coordinated collective bargaining tend to have less inequality in wages, lower and less persistent unemployment, and fewer and shorter strikes than countries where collective bargaining is less established.

Legal Instruments

There are many international instruments that affirm and guarantee the right of freedom of association. Such instruments place requirements on States to protect and respect these rights. The right to freedom of association and collective bargaining is one of five fundamental rights and principles at work which member states have to promote irrespective of whether or not they have ratified the respective conventions.

- Freedom of association is considered a fundamental right at work under the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work. The right of workers and employers to form and join organizations of their own choosing is also protected by two specific ILO conventions: Convention 87 and Convention 98. According to ILO standards, freedom of association and the right to organize is not only considered a labour right, but also a human right.

- As a human right, freedom of association is proclaimed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) signed in 1948. Article 23(4) of the UDHR affirms the right to form and join trade unions.

- In addition, freedom of association is affirmed in article 22 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and article 8 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), both adopted in 1966. Both provisions state that freedom of association, as a human right, includes the right to form and join trade unions to protect one’s interests. Restrictions on the right to associate freely are subject to strict conditions: any restrictions must be prescribed by law and must be necessary in a democratic society.

- Furthermore, the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers pays extra attention to the case of migrant workers through explicitly recognizing the right to freedom of association in the case of migrant workers: migrant workers and members of their families have the right to join any trade union or any association.

The freedom of association is included as one of the Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact: “Principle 3: Businesses should uphold the freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining”. The four labour principles of the UN Global Compact are derived from the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work.

These fundamental principles and rights at work have been affirmed and developed in the form of specific rights and obligations in International Labour Conventions and Recommendations and cover issues related to child labour, discrimination at work, forced labour and freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining.

Member States of the ILO have an obligation to uphold the freedom of association, even if they have not ratified the Conventions in question.

Regional and Domestic Legislation

Companies are increasingly subject to non-financial reporting and due diligence obligations in the jurisdictions in which they operate, which often include disclosures on their performance. There are several high-profile examples of national legislation that specifically mandate human rights-related reporting and other positive legal duties, including the United Kingdom Modern Slavery Act 2015, Australian Modern Slavery Act 2018, the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act 2010, the French Corporate Duty of Vigilance Law 2017, German Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains 2021 and the Norwegian Transparency Act 2022.

Also, in 2021 the Netherlands submitted a Bill for Responsible and Sustainable International Business Conduct, and the European Commission announced its Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). This Directive is likely to come into force between 2025 and 2027 and will make human rights and environmental due diligence mandatory for larger companies.

These mandatory due diligence and disclosure laws require companies to publicly communicate their efforts to address actual and potential human rights impacts, including violations in relation to freedom of association. Failure to comply with these obligations leads to real legal risk for companies.

Contextual Risk Factors

Restrictions to the enjoyment of the right to freedom of association are driven by multiple underlying causes, from poor legal protections to company practices that discourage workers from organizing. Key risk factors include:

- Inadequate legal frameworks offer a poor standard of legal protections of the right to freedom of association. This includes laws preventing workers from forming their own organizations freely or requiring compulsory union membership. Some countries do not afford migrant workers and public servants the right to freedom of association, even though this is in contravention to ILO standards.

- Government interference in the formal registration process of unions: Governments may obstruct the bureaucratic process necessary for the legal recognition of trade unions, or even refuse to legally recognize unions for spurious reasons. Governments may also seek to exert influence or control over legally registered unions.

- Weak enforcement of labour laws due to inadequate training, an under-resourced labour inspectorate or high levels of corruption. These contexts can enable local companies to discriminate against workers linked to unions and other workers’ groups or subject them to extreme abuses such as kidnapping or even murder. Ineffective judicial systems may hinder workers’ ability to remedy violations.

- Obstruction of union activity by companies can take many forms, including outright refusal by companies to recognize a trade union, threat of dismissal or other forms of retaliation because of workers exercising their right to free association.

- High levels of informality in a country’s workforce are indicative of poor working conditions and limited social protections. Where there are more workers in informal arrangements or precarious employment, membership of unions or other relevant organizations is generally much lower.

- Lack of understanding of rights to freedom of association among workers: Particularly in countries with low trade union density, workers may not be fully aware of their rights to unionize or engage in collective bargaining. Poor awareness of the right to independent worker representation can act as a major deterrent in the realization of the right to freedom of association.

Industry-specific Risk Factors

While barriers to the right to freedom of association exist in many industries, the following present particularly significant levels of risk. To identify potential risks to freedom of association for other industries, companies can access the CSR Risk Check.

Agriculture

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), agricultural sector workers face particular challenges to the enjoyment of the right to freedom of association due to high levels of poverty and informality among agricultural workers.

Agriculture-specific risk factors include the following:

- Informal employment: An overwhelming majority of agricultural workers — 93.6% — are not formally employed, and therefore face additional barriers to securing the right to free association given their informal or precarious working arrangements. They are often excluded from the coverage or implementation of national labour laws and social protections. Certain categories of workers — such as migrant workers, indigenous peoples and casual, seasonal or temporary workers — are particularly vulnerable. Yet they are more likely to be forced into the informal sector where it is much more difficult to organize.

- Labour providers: A common feature of the agriculture sector is the presence of labour providers, such as employment or recruitment agencies. The Private Employment Agencies Convention, 1997 (No. 181) includes provisions concerning the right of temporary placement workers to organize; however, in practice barriers to organizing are high, making it more challenging for these workers to secure independent representation to advocate on their behalf.

IUF is the global union federation that represents agriculture workers and can be an important source of information for companies undertaking due diligence in this sector.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Guidelines for Stakeholders on the Right to Freedom of Association in Agriculture: These guidelines outline specific challenges and opportunities that arise out of securing freedom of association in the agricultural sector.

- ILO, Giving a Voice to Rural Workers: General Survey Concerning the Right of Association and Rural Workers’ Organizations Instruments: This report examines the range of obstacles to the full realization of the right of agricultural workers to organize.

- OECD-FAO, Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains: This guidance provides a common framework to help agri-businesses and investors support sustainable development, including the protection of freedom of association.

- FAO, Regulating Labour and Safety Standards in the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Sectors: This resource provides information on international labour standards that apply in agriculture, including those on freedom of association, and their integration into national legislation.

- Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), From Farm to Table: Ensuring Fair Labour Practices in Agricultural Supply Chains: This resource provides guidelines on what investors should be looking for from companies to eliminate labour abuses in their supply chains, including ensuring the right to free association.

- Fairtrade International, Guide for Smallholder Farmer Organisations – Implementing Human Rights and Environmental Due Diligence (HREDD): This guidance was developed to provide advice and tools on HREDD for farmer organisations to implement.

Construction

Construction is a rapidly growing industry, and the proliferation of third-party recruitment agencies increases the risk of workers, the majority of whom are migrants, to labour rights violations. Migrant workers who are employed by third-party recruitment agencies are particularly vulnerable to exploitative working conditions and are often denied the right to join unions.

Construction-specific risk factors include the following:

- Difficult working conditions: Working conditions are notoriously demanding and dangerous, with high levels of industrial accidents. Without the ability to join trade unions or other independent workers’ organizations, construction workers are often unable to effectively voice concerns regarding unsafe conditions.

- Wage issues: Construction workers are particularly vulnerable to late or non-payment of wages for long periods as in many instances, contractors are not obliged to pay subcontractors until they have received payment from the client. Being blocked from joining unions hinders workers from raising these concerns.

- Migrant workers: In some countries, migrant workers are prohibited by law from joining trade unions. Even if they are formally allowed to unionize, migrant workers may often find it difficult to access trade union protection. This is particularly due to the lack of formal documentation, such as resident or work visas, which may make them hesitant to seek the protection of formal institutions. In this respect, migrant workers often face limitations in accessing remedy. Even those who have formal documentation may be hesitant to unionize and avoid raising labour-related grievances for fear of losing their jobs or being deported. Migrant workers may also experience other difficulties with access to complaint mechanisms, due to language difficulties or hidden fees that they may not be able to afford.

Building and Woodworkers International is the global union federation that represents construction workers and can be an important source of information for companies undertaking due diligence in this sector.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Migrant Work & Employment in the Construction Sector: This resource looks at some of the barriers migrant workers can face in accessing adequate labour standards in the construction sector, including barriers to unionization. It includes recommendations for employers on how to ensure better working conditions for migrant workers.

- Business and Human Rights Resource Centre, A Human Rights Primer for Business: Understanding Risks to Construction Workers in the Middle East: This resource provides specific regional advice for construction companies operating in the Middle East for key human rights risks to look out for, including violations of the right to free association.

- BSR, Addressing Workers’ Rights in the Engineering and Construction Sector: This report looks at the challenges faced by engineering and construction companies to uphold workers’ rights, including restrictions to unionization. It provides proposed options for collaboration between stakeholders in the construction industry in tackling human rights issues, including ensuring the right to freedom of association.

- Building Responsibly, Principle 9: Worker Representation is Respected: This guidance note provides members of the industry coalition advice on how to navigate potential challenges surrounding issues related to freedom of association. It provides recommendations for companies on how to build better labour relations with workers.

Fashion and Apparel

The fashion and apparel industry is likely to be linked to violations of the right to freedom of association.

Fashion and apparel specific risk factors include the following:

- Subcontracting: The apparel manufacturing industry features a lot of subcontracting and outsourcing, which typically involves informal or casual employment arrangements. Workers in such precarious employment situations often lack union representation, making it challenging for them to secure decent working conditions.

- South-East Asia: Major apparel manufacturing countries in South-East Asia are known to resort to repressive measures to contain union activity. Unionists and workers in such countries face exacerbated risks of being subject to excessive use of force by police or arbitrary detention while engaging in union activity, such as strikes or demonstrations.

IndustriALL is the global union federation that represents textile and garment workers and can be an important source of information for companies undertaking due diligence in this sector.

Helpful Resources

- OECD, Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains in the Garment & Footwear Sector: This guidance aims to help fashion and apparel businesses implement the due diligence recommendations contained in the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises in order to avoid and address the potential negative impacts of their activities and supply chains on a range of human rights, including the right of free association.

- PRI, An Investor Briefing on the Apparel Industry: Moving the Needle on Labour Practices: This resource guides institutional investors on how to identify the scope for negative human rights impacts in the apparel industry, including those pertaining to freedom of association.

- Fair Wear Foundation, Code of Labor Practices (CoLP) Standard on Freedom of Association and Collective Bargaining: A policy guide for Fair Wear members to ensure workers enjoy freedom of association.

Mining and the Extractives Industry

The extractives industry has frequently been linked to violations of the right to freedom of association. Trade union associations are active and organized in large-scale mining (LSM), particularly through IndustriALL, the global union federation in this sector. Ongoing campaigns suggest that occupational health and safety, dismissal of workers, wages and working hours are among the most pertinent labour issues for trade unions operating in the LSM sector.

Artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM), by contrast, remains largely informal and nonunionized, despite its significant contribution to economies of major mining countries (particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa). As a result, many ASM workers remain unprotected. IndustriALL has recently called for the formalization of ASM activities, which would mean the extension of trade union coverage to also include ASM workers.

Risk factors specific to the extractive industry include the following:

- Remote operations: Extractive operations often take place in remote or underdeveloped regions, where there are few other options in terms of employment. This puts workers in a vulnerable position, where they can feel pressured not to raise grievances related to working conditions to employers, for fear of termination of employment or receiving other sanctions. Losing employment at a mine often means the loss of a household’s only source of income.

- Difficult working conditions: Working conditions in the mining industry are often demanding and dangerous. Frequent reports of companies blocking attempts by workers to unionize or strike hinder their ability to effectively voice concerns regarding unsafe conditions.

- Labour providers: Increasingly, workers are recruited through agencies or other types of labour contractors. These workers are frequently excluded from social protections such as medical benefits, employment accident and disease benefits, and other allowances. They may also be dismissed more easily and quickly and face little prospect of their contracts being regularized. As contract workers, they face even more significant barriers to freedom of association and are put in an even more vulnerable position than workers with independent representation.

Workers in some oil and gas exporting countries face high security and human rights risks when trying to form and join unions or engage in collective bargaining. Companies may be hostile to workers’ organizations. In many countries, security providers target union leaders and prevent companies from creating associations.

Helpful Resources

- Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC), Standards Guidance: This guidance provides a suggested approach for RJC members to implement the mandatory requirements of the RJC Code of Practice (COP), including respecting the right of employees to associate freely.

- IPIECA, Worker Grievance Mechanisms: Guidance Document for the Oil and Gas Industry: This resource was developed to help oil and gas companies engage with worker grievance mechanisms, particularly with trade unions and labour forums.

Electronics Manufacturing

The electronics manufacturing industry poses freedom of association risks, with major electronics, telecommunications and technology brands facing allegations of labour rights violations, including imposing barriers to freedom of association.

Industry-specific risk factors include the following:

- Job competition: Competition for jobs in the industry can be strong, particularly with respect to famous brands. This can result in workers, including apprentices or work experience candidates, working excessive hours without adequate rest. It also puts workers in a position where they may be hesitant to raise grievances regarding working conditions through unions or other workers’ groups.

- Students: Student workers are given compulsory placements in electronics manufacturing factories, modelled as “internships”, where they are forced to work excessive hours and often go unpaid or earn extremely low wages. These student workers are typically excluded from union representation and lack access to recourse mechanisms.

- Recruitment fees: Migrant workers are often subject to excessive recruitment fees, which often plunge them into debt bondage even before the start of employment. Their vulnerable positions put them in a situation where they are often too scared or unwilling to join trade unions.

IndustriALL is the global union federation that represents workers in the electronics sector and can be an important source of information for companies undertaking due diligence.

Helpful Resources

- SOMO, Freedom of Association in the Electronics Industry: This paper examines monitoring and auditing efforts of electronics manufacturing companies to ensure workers have the right to freedom of association. It provides recommendations for companies on how to positively influence freedom of association in their supply chain.

Hospitality

The hospitality sector is linked to significant freedom of association risks, particularly when it involves migrant workers or other vulnerable groups, such as individuals hired through non-traditional employment arrangements.

Hospitality-specific risk factors include the following:

- Outsourcing: Much of the hospitality sector relies on the outsourcing of services, such as cleaning, maintenance, and security. Workers who are recruited by outsourcing methods, such as through subcontractors or third-party labour suppliers, often lack worker representation or face barriers to freedom of association.

- Migrant workers in the Middle East: Migrant workers employed in countries such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) or Qatar face significant restrictions to freedom of association by law. Without intervention or facilitation by companies themselves to ensure that workers are adequately represented and have access to grievance mechanisms, migrant workers in these jurisdictions will be at significant risk of freedom of association violations.

IUF is the global union federation that represents hotel and restaurant workers and can be an important source of information for companies undertaking due diligence in this sector.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Guidelines on Decent Work and Socially Responsible Tourism: These guidelines provide practical information for developing and implementing policies and programmes to promote sustainable tourism and strengthen labour rights protection, including freedom of association.

- Business and Human Rights Resource Centre, Inhospitable: How Hotels in Qatar & the UAE are Failing Migrant Workers: This report provides details on how companies in the UAE can uphold freedom of association principles, by looking at specific recommendations on introducing labour standards and conducting robust human rights due diligence.

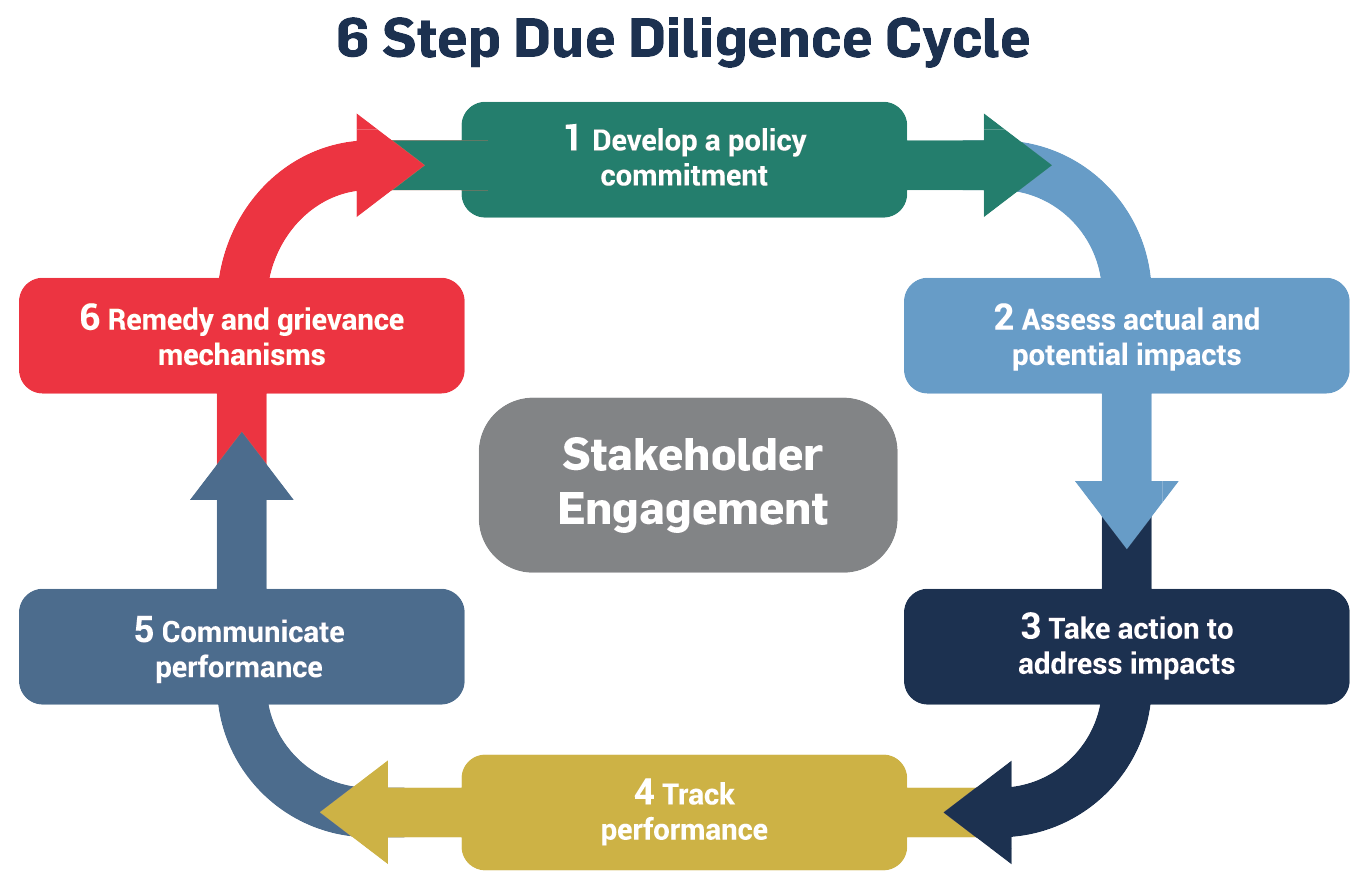

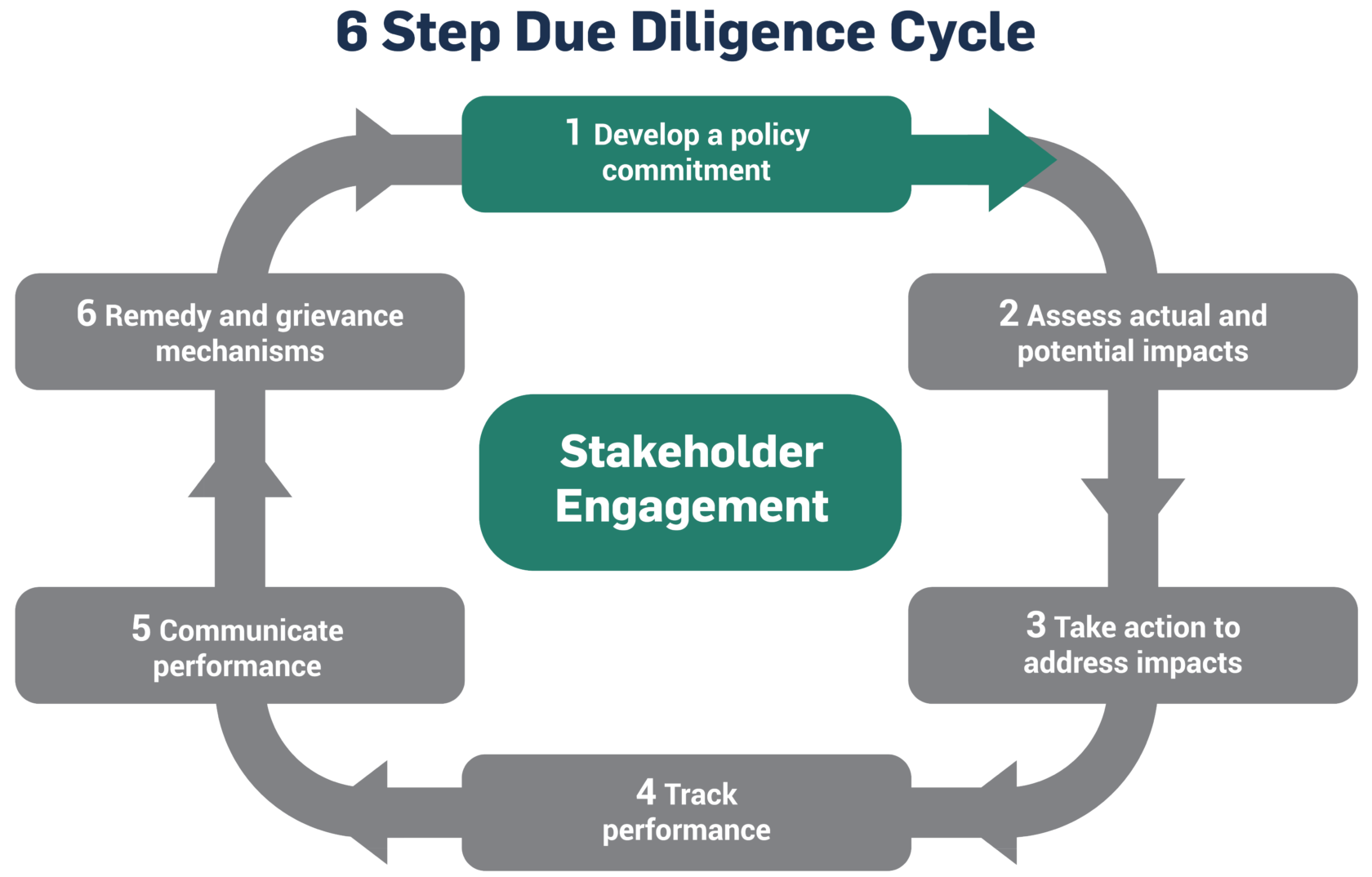

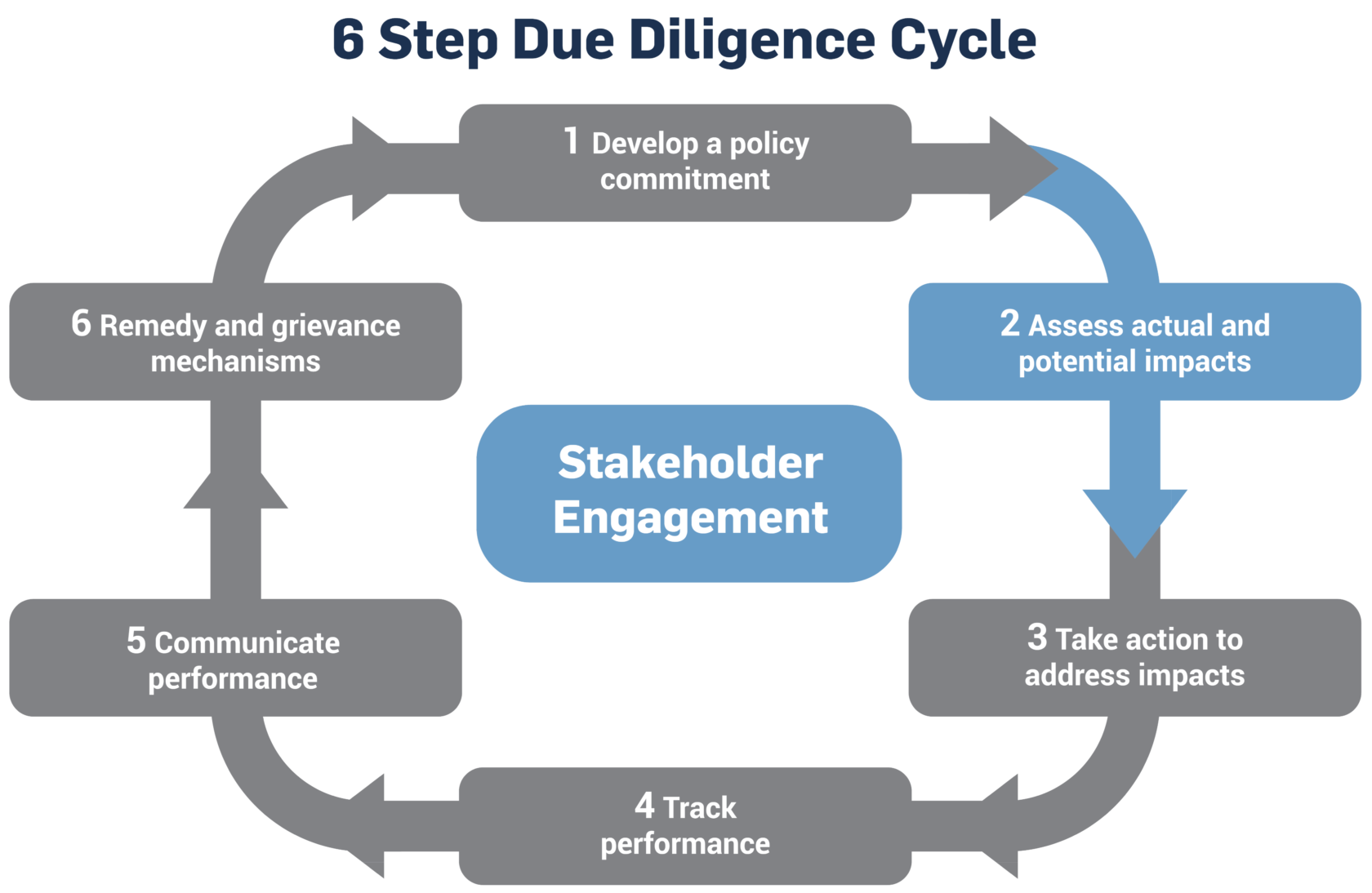

Due Diligence Considerations

This section outlines due diligence steps that companies can take to prevent working time violations in their operations and supply chains. The described due diligence steps are aligned with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). Further information on UNGPs is provided in the ‘Key Human Rights Due Diligence Frameworks’ section below or in the Introduction.

While the below steps provide guidance on working time in particular, it is generally more resource-efficient for companies to ‘streamline’ their human rights due diligence processes by also identifying and addressing other relevant human rights issues (e.g. child labour, forced labour, discrimination, freedom of association) at the same time.

Key Human Rights Due Diligence Frameworks

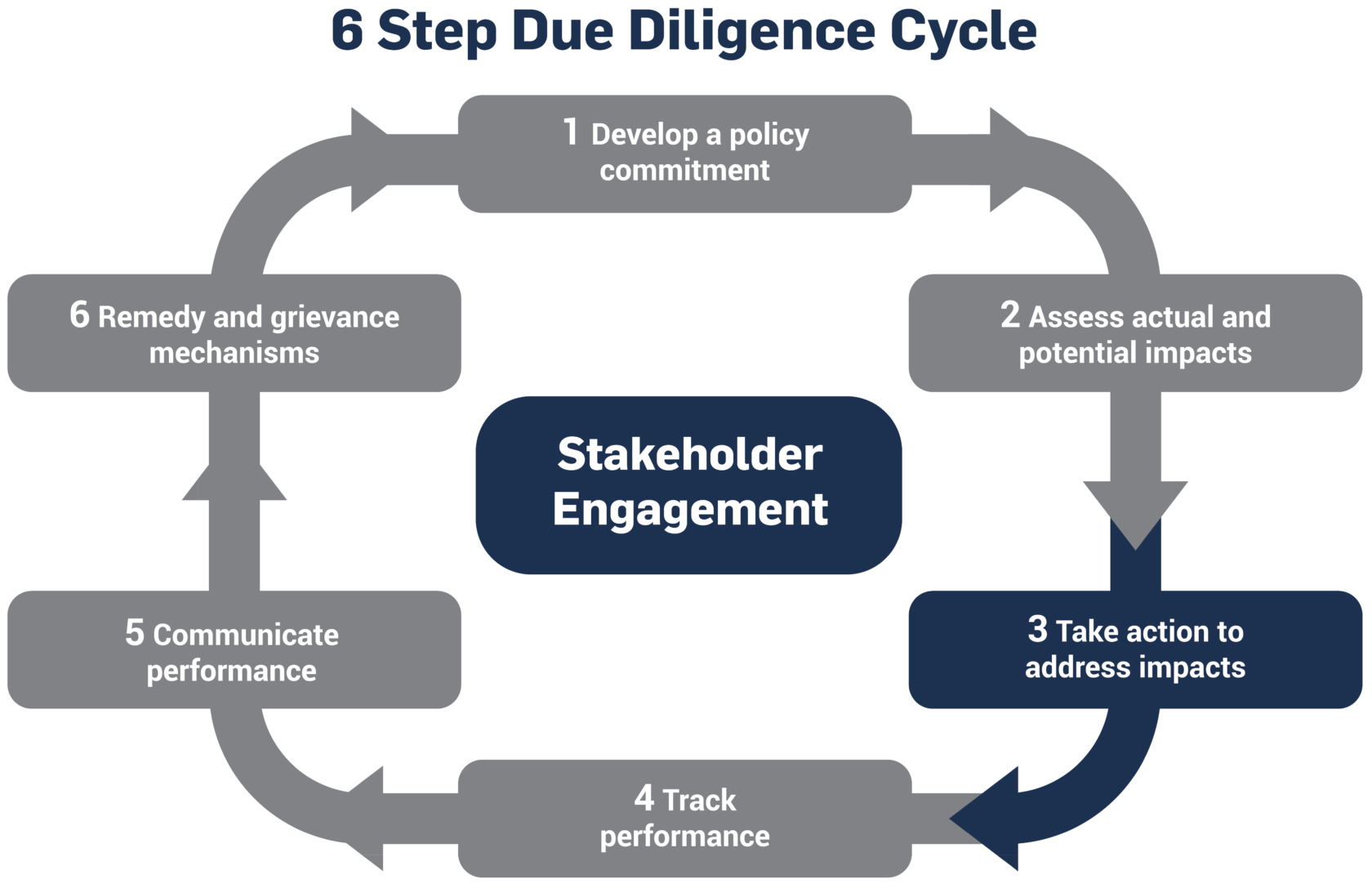

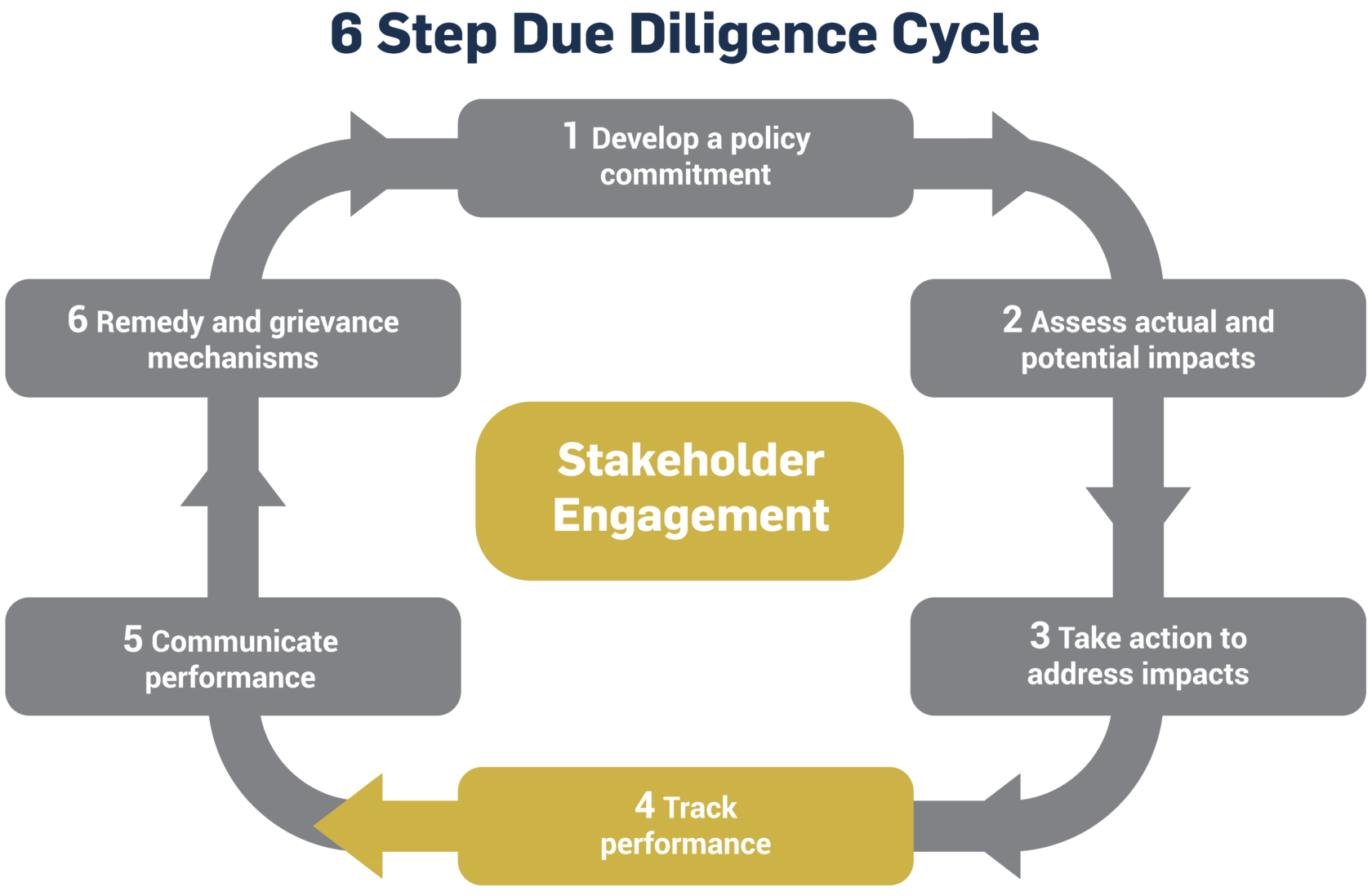

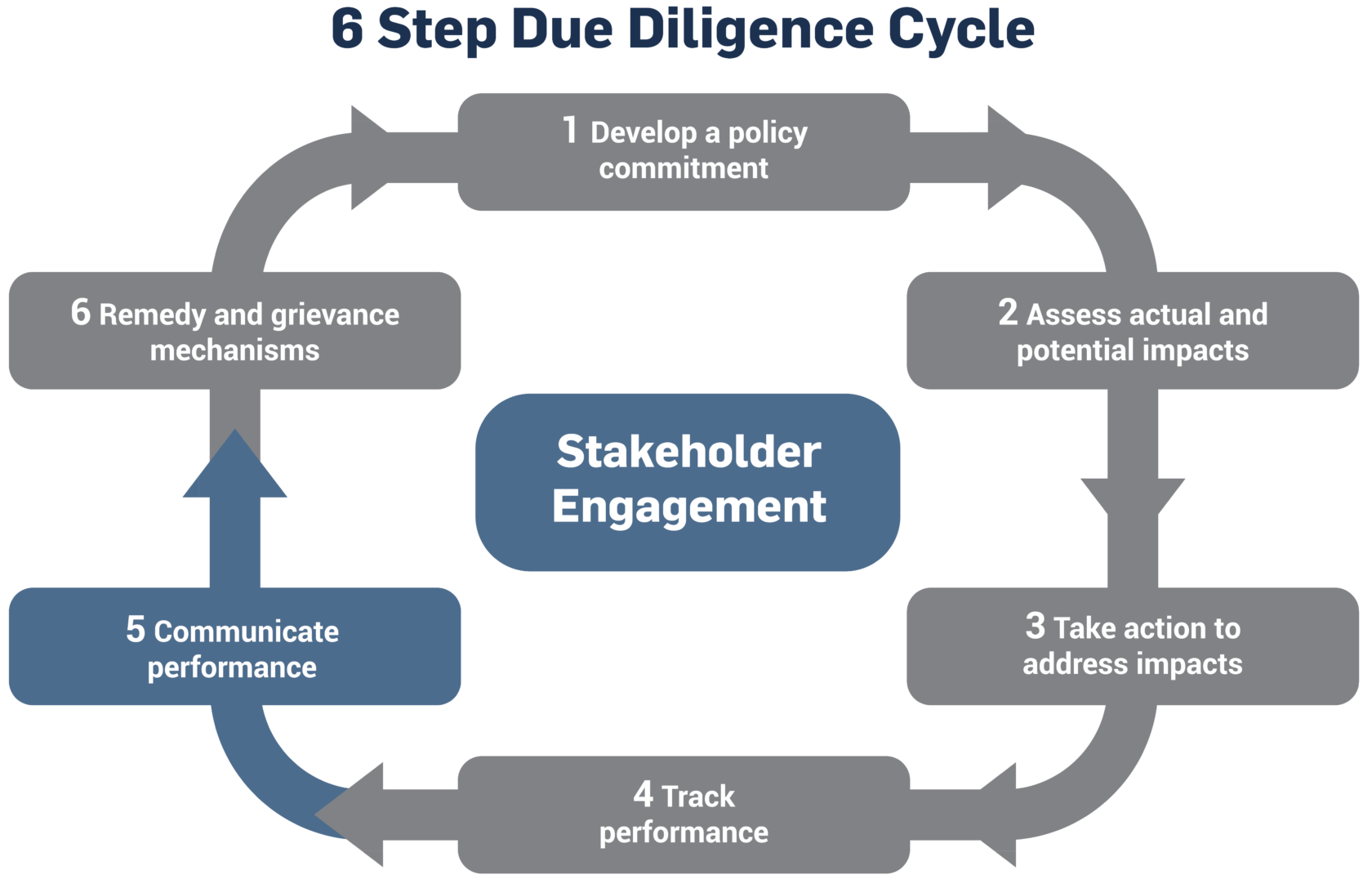

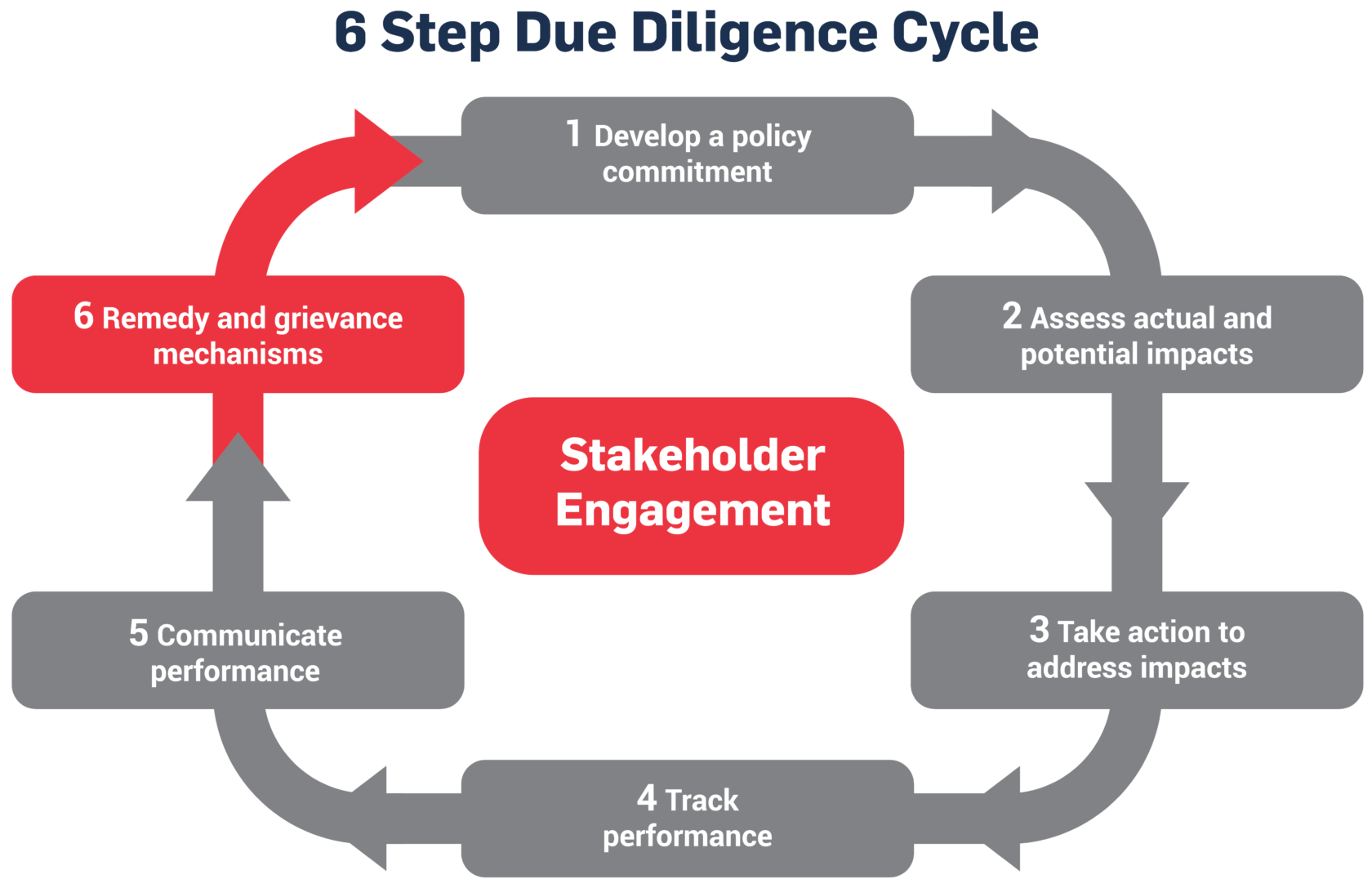

Several human rights frameworks describe the due diligence steps that businesses should ideally implement to address human rights issues, including freedom of association. The primary framework is the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). Launched in 2011, the UNGPs offer guidance on how to implement the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework, which establishes the respective responsibilities of Governments and businesses — and where they intersect.

The UNGPs set out how companies, in meeting their responsibility to respect human rights, should put in place due diligence and other related policies and process, which include:

- A publicly available policy setting out the company’s commitment to respect human rights;

- Assessment of any actual or potential adverse human rights impacts with which the company may be involved across its entire value chain;

- Integration of the findings from their impact assessments into relevant internal functions/processes — and the taking of effective action to manage the same;

- Tracking of the effectiveness of the company’s management actions;

- Reporting on how the company is addressing its actual or potential adverse impacts; and

- Remediation of adverse impacts that the company has caused or contributed to.

The steps outlined below follow the UNGPs framework and can be considered a process which a business looking to start implementing human rights due diligence processes can follow.

Additionally, the OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises define the elements of responsible business conduct, including human and labour rights.

Another important reference document is the ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy (MNE Declaration), which contains the most detailed guidance on due diligence as it pertains to labour rights.

Paragraph 10(e) of the MNE Declaration, identified the central role of freedom of association in undertaking due diligence on labour issues: “In order to gauge human rights risks, enterprises — including multinational enterprises — should identify and assess any actual or potential adverse human rights impacts with which they may be involved either through their own activities or as a result of their business relationships. This process should involve meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups and other relevant stakeholders including workers’ organizations, as appropriate to the size of the enterprise and the nature and context of the operation. For the purpose of achieving the aim of the MNE Declaration, this process should take account of the central role of freedom of association and collective bargaining as well as industrial relations and social dialogue as an ongoing process.”

Companies can seek specific guidance on this and other issues relating to international labour standards from the ILO Helpdesk for Business. The ILO Helpdesk assists company managers and workers who want to align their policies and practices with principles of international labour standards and build good industrial relations. It has a specific section on freedom of association.

Additionally, the SME Compass offers guidance on the overall human rights due diligence process by taking businesses through five key due diligence phases. The SME Compass has been developed in particular to address the needs of SMEs but is freely available and can be used by other companies as well. The tool, available in English and German, is a joint project by the German Government’s Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

1. Develop a Policy Commitment on Freedom of Association

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, a human rights policy should be:

- “Approved at the most senior level” of the company;

- “Informed by relevant internal and/or external expertise”;

- Specific about company’s “human rights expectations of personnel, business partners and other parties directly linked to its operations, products or services”;

- “Publicly available and communicated internally and externally to all personnel, business partners and other relevant parties”; and

- “Reflected in operational policies and procedures necessary to embed it throughout the business”.

As part of their policy commitment to respect human rights, companies should commit to not restricting workers’ rights to join a trade union/workers’ organization and to associate freely. Such a policy should be compliant with national laws and regulations. However, where the right to freedom of association is restricted under law, companies should find ways to allow workers to collectively express their concerns and have a dialogue with management, which is at the same time consistent with national law, and to provide assistance to business partners to do so.

Businesses may want to consider including the following aspects in their human rights policy to demonstrate their commitment to freedom of association:

- Include a reference to the ILO Convention on Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organize (No. 87) and ILO Convention on the Right to Organize and Collective Bargaining (No. 98);

- Formally acknowledge workers’ right to freely join organizations of their own choosing without previous authorization or fear of intimidation or reprisal;

- Include a commitment to upholding the ILO Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work;

- Commit the organization not to interfere in workers’ decisions to associate, not to influence their decision in any way and not to discriminate against workers who choose to associate;

- Recognize the right of workers to elect their own representatives without interference;

- Inform workers about the benefits of joining a union; and

- Make clear the company’s expectations toward personnel, business partners and other parties directly linked to its operations, products or services.

The policy commitment on freedom of association should:

- Be developed involving staff in key internal functions and wider labour rights expertise from inside and outside the company;

- Go through a meaningful consultation process with relevant stakeholders, particularly workers’ representative organizations;

- Be approved at the most senior level of the company;

- Be publicly available and communicated internally and externally to all staff, business partners and other relevant parties;

- Be available in relevant languages and be communicated in a manner that considers the different needs of various audiences; and

- Have appropriate internal accountability for its implementation.

Although some companies have developed stand-alone policies on freedom of association (for example, Vestas), it is most common for businesses to integrate commitments to freedom of association in other policy documents such as a human rights policy (H&M, Unilever and Coca-Cola) or a code of conduct (Meiji, Olam and General Mills).

Businesses may also consider aligning their policies with relevant industry-wide or cross-industry policy commitments, for example:

- Responsible Business Alliance (RBA) Code of Conduct

- Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI) Base Code

- amfori BSCI Code of Conduct

- Fair Labor Association (FLA) Code of Conduct

Additionally, businesses could enter into a Global Framework Agreement (GFA) with the relevant global union federation that represents workers at the international sectoral level. GFAs put in place standards of trade union rights, health, safety and environmental practices, and quality of work principles across a company’s global operations, regardless of whether those standards exist in an individual country; and may also include provisions for workers’ rights in the supply chain. Examples of companies that have entered into GFAs with IndustriALL include ASOS, Inditex, BMW, Bosch and Volkswagen. The ILO, in cooperation with the European Commission, has developed a searchable database of GFAs signed by companies from around the world.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Helpdesk for Business on International Labour Standards: This resource provides answers to the most common questions that businesses may encounter while developing their policy documents that include freedom of association commitments.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Freedom of Association in Company Supply Chains: This guide provides a sample policy commitment to freedom of association.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, FOA & Worker Representation: A 5-step roadmap to implementing freedom of association, with Step 1 focusing on policy commitments.

- United Nations Global Compact, The Labour Principles of the UN Global Compact: A Guide for Business: The purpose of this guide is to increase the understanding of the four labour principles of the UN Global Compact, as well as to provide an inventory of key resources to help integrate these principles into business operations.

- United Nations Global Compact-OHCHR, A Guide for Business: How to Develop a Human Rights Policy: This guidance provides recommendations on how to develop a human rights policy and includes extracts from companies’ policies referencing freedom of association.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to develop a human rights strategy and formulate a policy statement.

- SME Compass, Policy statement: Companies can use this practical guide to learn to develop a policy statement step-by-step. Several use cases illustrate how to implement the requirements.

- United Nations Global Compact and ILO, Advancing decent work in business Learning Plan: This learning plan, helps companies understand each Labour Principle and its related concepts and best practices as well as practical steps to help companies understand and take action across a variety of issues.

2. Assess Actual and Potential Impacts on Freedom of Association

UNGP Requirements

The UNGPs note that impact assessments:

- Will vary in complexity depending on “the size of the business enterprise, the risk of severe human rights impacts, and the nature and context of its operations”;

- Should cover impacts that the company may “cause or contribute to through its own activities, or which may be directly linked to its operations, products or services by its business relationships”;

- Should involve “meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups and other relevant stakeholders” in addition to other sources of information such as audits; and

- Should be ongoing.

Impact assessments should look at both actual and potential impacts, i.e. impacts that have already manifested or could manifest. This compares to risk assessment that would only look at potential impacts and may not satisfy all of the above criteria.

Freedom of association risk assessments are most often integrated into broader assessment of human rights impacts (for example Nestlé, Unilever and Electrolux). Understanding where in the supply chain the action on promoting freedom of association is most needed and (as a second consideration) where a company can exercise more influence are key steps.

Companies can assess freedom of association risks in countries where they operate and source from by:

- Identifying highest risk countries and regions for violations of freedom of association;

- Assessing national and local law on freedom of association to identify any gaps (such as those that restrict migrant workers or public servants from unionizing);

- Regularly engaging with national and local federations of unions and employers, civil society groups and other companies sourcing from the same country to understand industrial relations in the country of interest;

- Engaging with workers during the conduct of site visits or audits, particularly in the absence of formal unions; and

- Assessing the risks to freedom of association further down the company supply chain, including the risks related to subcontracting arrangements, which do not favour stable industrial relations or unions.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations (CEARCR), Application of International Labour Standards 2021: This report allows companies to find out more about the state of the legislation and practice, at a country-level, related to specific labour standards, including freedom of association.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Freedom of Association in Company Supply Chains: This guide provides suggestions for risk analysis to identify which countries, suppliers or agencies are most likely to create difficulties for freedom of association. The guide also includes a sample supplier self-assessment questionnaire on freedom of association.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, FOA & Worker Representation: A 5-step roadmap to implementing freedom of association, with Step 2 focusing on risk assessment.

- ITUC, Global Rights Index 2021: Companies can use this resource to assess the risks to freedom of association globally, and to identify the highest risk countries and regions. This report looks at specific themes in relation to workers’ rights, such as the right to strike, collective bargaining and access to justice, which enables companies to identify which issues are most pertinent to their country of operation.

- OECD, Statistics on Trade Union Density: This OECD database enables companies to understand the extent of trade union density in countries, giving insight into the industrial relations environment where operations or suppliers are.

- United Nations SDGs, Indicator 8.8.2: This dataset provides information on the level of national compliance with regards to freedom of association and collective bargaining based on ILO textual sources and national legislation.

- CSR Risk Check: A tool allowing companies to check which international CSR risks (including related to freedom of association) businesses are exposed to and what can be done to manage them. The tool provides tailor-made information on the local human rights situation as well as environmental, social and governance issues. It allows users to filter by product/raw material and country of origin. The tool was developed by MVO Netherland; the German version is funded and implemented by the German Government’s Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights and UPJ.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to assess actual and potential human rights risks and how to assess and prioritize risks.

- SME Compass, Risk Analysis Tool: This tool helps companies to locate, asses and prioritize significant human rights and environmental risks long their value chains.

- SME Compass, Supplier review: This practical guide helps companies to find an approach to manage and review their suppliers with respect to human rights impacts.

3. Integrate and Take Action on Freedom of Association

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, effective integration requires that:

- “Responsibility for addressing [human rights] impacts is assigned to the appropriate level and function within the business enterprise” (e.g. senior leadership, executive and board level);

- “Internal decision-making, budget allocations and oversight processes enable effective responses to such impacts”.

International instruments identify several actions that companies can implement to respect freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining. Companies can take action at different levels, including in the workplace and in the community of operation.

Actions in the workplace:

- Recognize that all workers are free to form and/or join a trade union of their choice. Do not interfere with workers’ exercise of this right;

- Should the workers in your company choose to join or form a union, recognize it and engage in dialogue;

- Put in place non-discriminatory policies and procedures with respect to trade union organization, union membership and activity in such areas as applications for employment and decisions on advancement, dismissal or transfer;

- Provide internal training/capacity building for the direct workforce to raise awareness of the right to freedom of association and best practice;

- Provide training/capacity building for relevant business relationships (partners, suppliers, clients, etc.) that are involved with the risk/impact about how to respect workers’ right to freedom of association;

- Allow for election of free and independent workers’ representatives and recognize the duly elected representatives;

- Provide worker representatives with appropriate facilities to assist in the development of effective collective bargaining;

- Participate in good faith in collective bargaining with a view to the regulation of terms and conditions of employment by means of collective agreements;

- Consult regularly with the relevant workers’ organizations;

- Where the right to freedom of association and/or collective bargaining is restricted under law, find ways to allow the workers to collectively express their concerns and have a dialogue with management, which is at the same time consistent with national law, and provide assistance to business partners to do so;

- Consider establishing a global framework agreement with the relevant global union federation(s); consider also including provisions concerning freedom of association in the company’s supply chain;

- Screen and select new suppliers against a policy/code that recognizes the right to freedom of association for all workers; and

- Assess existing suppliers against a policy/code that recognizes the right to freedom of association for all workers.

Actions in the community/country of operation:

- Engage with peer companies to use collective action/leverage to advance respect for freedom of association;

- Engage through multi-stakeholder action/leverage to advance respect for freedom of association;

- Engage with governmental or regulatory bodies whose action/leverage can help advance respect for freedom of association; and

- Engage with other organizations or individuals whose action/leverage can help advance respect for freedom of association.

Helpful Resources

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Freedom of Association in Company Supply Chains: This guide provides suggestions for developing and implementing an action plan on freedom of association in supply chains, including ideas for a corrective action plan in case of breaches.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, FOA & Worker Representation: A 5-step roadmap to implementing freedom of association, with Step 3 focusing on strategy development and implementation and Step 5 focusing on acting, embedding and consolidating.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to take action on human rights by embedding them in your company, creating and implementing an action plan, and conducting a supplier review and capacity building.

- SME Compass, Identifying stakeholders and cooperation partners: This practical guide is intended to help companies identify and classify relevant stakeholders and cooperation partners.

- SME Compass, Standards Compass: This online tool offers guidance on what to pay attention to when selecting sustainability standards or when participating in multi-stakeholder initiatives. It allows comparing standards and initiatives with respect to their contribution to human rights due diligence and their potential limitations.

4. Track Performance on Freedom of Association

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, tracking should:

- “Be based on appropriate qualitative and quantitative indicators”;

- “Draw on feedback from both internal and external sources, including affected stakeholders” (e.g. through grievance mechanisms).

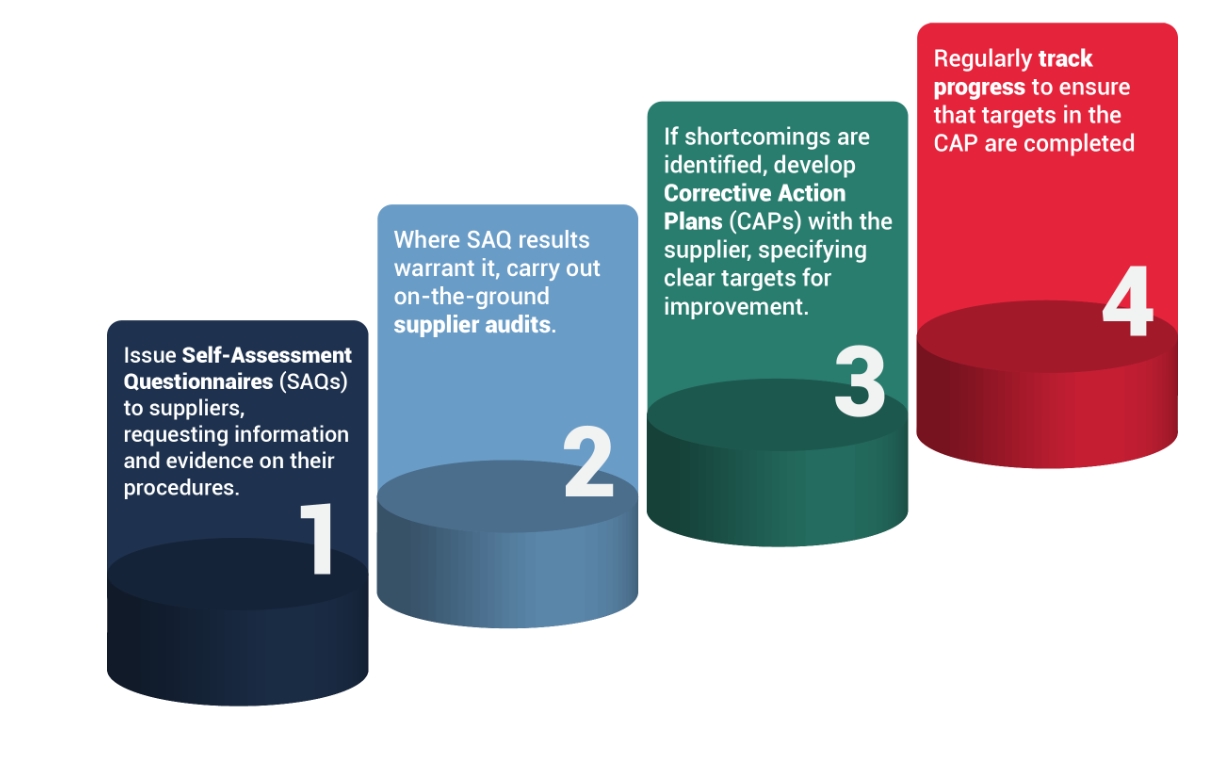

Companies can track performance on the implementation of the freedom of association action plan by conducting audits. It is, however, essential for companies to vet social auditors carefully as freedom of association has been identified as one of the weakest areas of audit practice. Auditors should be selected based on their interpersonal skills as well as specialist knowledge on freedom of association.

In addition to audits, companies could consider adopting the following strategies to track their performance:

- Reviewing termination records and exit interviews to determine if departing workers referred to discrimination based on union membership or serving as a worker representative;

- Conversations with managers and supervisors to ensure they understand and effectively implement freedom of association policy and procedures;

- Regular engagements with workers themselves through site visits, surveys or other ways of communication;

- Regular engagements with local stakeholders such as grassroots unions and NGOs to have a better sense of the local environment with respect to freedom of association;

- Periodically reviewing recruitment, selection and hiring records to ensure that there is no discrimination against job applicants with union affiliation; and

- Routinely reviewing complaints and grievances from workers related to freedom of association.

To track performance on freedom of association, businesses could also establish and track specific targets and KPIs, including:

- Percentage of workers surveyed who understand their rights to freedom of association;

- Percentage of workers who believe the company/supplier respects those rights.

Helpful Resources

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Freedom of Association in Company Supply Chains: This guide provides suggestions for monitoring the effectiveness of an action plan on freedom of association in supply chains, including an effective auditing checklist and useful questions for auditors.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to measure human rights performance.

- SME Compass: Key performance indicators for due diligence: Companies can use this overview of selected quantitative key performance indicators to measure implementation, manage it internally and/or report it externally.

5. Communicate Performance on Freedom of Association

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, regular communications of performance should:

- “Be of a form and frequency that reflect an enterprise’s human rights impacts and that are accessible to its intended audiences”;

- “Provide information that is sufficient to evaluate the adequacy of an enterprise’s response to the particular human rights impact involved”; and

- “Not pose risks to affected stakeholders, personnel or to legitimate requirements of commercial confidentiality”.

Companies are expected to communicate their performance on freedom of association in a formal public report, which can be achieved via companies’ broader sustainability or human rights reporting (such as Unilever’s Human Rights reports or M&S Human Rights reports). An additional way of communication can be made via companies’ annual Communication on Progress (CoP) in implementing the Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact. Other forms of communication may include in-person meetings, online dialogues and consultation with affected stakeholders.

Helpful Resources

- Ethical Trading Initiative, FOA & Worker Representation: A 5-step roadmap to implementing freedom of association, with Step 4 focusing on communication and remediation.

- Global Reporting Initiative, GRI 407: Freedom of Association and Collective Bargaining: This GRI standard provides detailed guidance on how organizations can report their management approach to freedom of association and collective bargaining.

- UNGP Reporting Framework: A short series of smart questions (‘Reporting Framework’), implementation guidance for reporting companies, and assurance guidance for internal auditors and external assurance providers.

- United Nations Global Compact, Communication on Progress (CoP): The CoP ensures further strengthening of corporate transparency and accountability, allowing companies to better track progress, inspire leadership, foster goal-setting and provide learning opportunities across the Ten Principles and SDGs.

- The Sustainability Code: A framework for reporting on non-financial performance that includes 20 criteria, including on human rights and employee rights.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to communicate progress on human rights due diligence.

- SME Compass, Target group-oriented communication: This practical guide helps companies to identify their stakeholders and find suitable communication formats and channels.

6. Remedy and Grievance Mechanisms

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, remedy and grievance mechanisms should include the following considerations:

- “Where business enterprises identify that they have caused or contributed to adverse impacts, they should provide for or cooperate in their remediation through legitimate processes”;

- “Operational-level grievance mechanisms for those potentially impacted by the business enterprise’s activities can be one effective means of enabling remediation when they meet certain core criteria”.

To ensure their effectiveness, grievance mechanisms should be:

- Legitimate: “enabling trust from the stakeholder groups for whose use they are intended, and being accountable for the fair conduct of grievance processes”

- Accessible: “being known to all stakeholder groups for whose use they are intended, and providing adequate assistance for those who may face particular barriers to access”

- Predictable: “providing a clear and known procedure with an indicative time frame for each stage, and clarity on the types of process and outcome available and means of monitoring implementation”

- Equitable: “seeking to ensure that aggrieved parties have reasonable access to sources of information, advice and expertise necessary to engage in a grievance process on fair, informed and respectful terms”

- Transparent: “keeping parties to a grievance informed about its progress, and providing sufficient information about the mechanism’s performance to build confidence in its effectiveness and meet any public interest at stake”

- Rights-compatible: “ensuring that outcomes and remedies accord with internationally recognized human rights”

- A source of continuous learning: “drawing on relevant measures to identify lessons for improving the mechanism and preventing future grievances and harms”

- Based on engagement and dialogue: “consulting the stakeholder groups for whose use they are intended on their design and performance, and focusing on dialogue as the means to address and resolve grievances”

The ILO MNE Declaration moreover states that “[m]ultinational as well as national enterprises should respect the right of the workers whom they employ to have all their grievances processed in a manner consistent with the following provision: any worker who, acting individually or jointly with other workers, considers that he or she has grounds for a grievance should have the right to submit such grievance without suffering any prejudice whatsoever as a result, and to have such grievance examined pursuant to an appropriate procedure. This is particularly important whenever the multinational enterprises operate in countries which do not abide by the principles of ILO Conventions pertaining to freedom of association, to the right to organize and bargain collectively, to discrimination, to child labour and to forced labour.”

In addition, “multinational enterprises should use their leverage to encourage their business partners to provide effective means of enabling remediation for abuses of internationally recognized human rights.”

Freedom of association-focused remedial actions can include:

- Ensuring that workers who have been discriminated against (e.g. in hiring, job assignment, compensation, demotion or transfer) and/or unfairly dismissed due to anti-union actions have their employment reinstated with back pay;

- Ensuring that declarations of loyalty or other similar commitment not to form or join a union are not imposed as a condition for reinstatement.

Grievance mechanisms can play an important role in helping to identify and address freedom of association issues in operations and supply chains — see Tchibo, Inditex and Lego for examples of companies with grievance mechanisms for workers. The ETI guide on freedom of association notes several points to consider with regard to grievance mechanisms, including:

- Having a grievance mechanism alone is no substitute for a genuine trade union chosen by the workers;

- All stages of the grievance process should be transparent and systematically recorded; and

- Worker grievances should not be seen as a threat but as an opportunity to learn and improve a company’s policy and processes.

Helpful Resources

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Freedom of Association in Company Supply Chains: This guide outlines considerations for setting up a grievance mechanism as a complement to a trade union within a company.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, FOA & Worker Representation: A 5-step roadmap to implementing freedom of association, with Step 4 focusing on communication and remediation.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Access to Remedy: Practical Guidance for Companies: This guidance explains key components of the mechanisms that allow workers to submit complaints and enable businesses to provide remedy.

- Global Compact Network Germany, Worth Listening: Understanding and Implementing Human Rights Grievance Management: A business guide intended to assist companies in designing effective human rights grievance mechanisms, including practical advice and case studies. Also available in German.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to establish grievance mechanisms and manage complaints.

- SME Compass, Managing grievances effectively: Companies can use this guide to design their grievance mechanisms more effectively – along the eight UNGP effectiveness criteria – and it includes practical examples from companies.

Case Studies

This section includes examples of company actions to promote freedom of association in their operations and supply chains.

Further Guidance

Examples of further guidance on freedom of association include:

- United Nations Global Compact, The Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact: The Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact provide universal guidance for sustainable business in the areas of human rights, labour, the environment and anti-corruption. Principle 3 calls on businesses to uphold the freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining.

- ILO, Committee on Freedom of Association: The Compilation of decisions of the Committee on Freedom of Association (CFA) is a searchable database of CFA conclusions in specific cases.

- ILO, Freedom of Association and Development: This resource provides ideas for employers’ organizations on how to work with trade unions, Governments and other relevant stakeholders to achieve sustainable development.

- ILO, In Search of Decent Work — Migrant Workers’ Rights: A Manual for Trade Unions: This manual is primarily targeted at trade unionists; however, companies may use it to understand the importance of protecting migrant workers’ rights and adopting a gender-sensitive approach in protecting free association rights in supply chains.

- ILO, Freedom of Association in Practice: Lessons Learned: This report provides guidance for employers’ organizations on how to engage with the informal sector to ensure free association rights. It also provides ideas on how to strengthen employers’ organizations.

- ILO Helpdesk for Business, Country Information Hub: This resource can be used to inform human rights due diligence, providing specific country information on different labour rights.

- SME Compass, Due Diligence Compass: This online tool offers guidance on the overall human rights due diligence process by taking businesses through five key due diligence phases.

- SME Compass, Standards Compass: This online tool offers guidance on what to pay attention to when selecting sustainability standards or when participating in multi-stakeholder initiatives. It allows comparing standards and initiatives with respect to their contribution to human rights due diligence and their potential limitations.

- SME Compass, Downloads: Practical guides and checklists are available for download on the SME compass website to embed due diligence processes, improve supply chain management and make mechanisms more effective.