Created in partnership with the Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights

Forced Labour

Almost 27.6 million people worldwide are trapped in forced or compulsory labour, with 17.3 million people subjected to forced labour in the private sector.Overview

What is Forced Labour?

Forced or compulsory labour is any work or service that is exacted from a person under the threat of penalty, and for which that person has not offered himself or herself voluntarily, according to the International Labour Organization (ILO). The notion of “threat of penalty” should be understood broadly. Penalties may comprise sanctions, including imprisonment, the threat or use of physical violence, psychological coercion, restrictions on the freedom of a worker, including preventing them from moving freely outside the work site. There may also be threats to harm a victim’s family, threats to denounce an illegal worker to the authorities, withholding identity documents, or withholding wages to compel a worker to stay in hopes of eventually being paid.

The terms “forced labour” and “modern slavery” are often used interchangeably as they have significant overlap. The key distinction is that modern slavery is generally defined as including forced marriage,[1] which is not addressed in this issue.

What is the Dilemma?

The dilemma for business is how to address the presence of forced labour within its operations and supply chains as it can be difficult to detect. Forced labour less often occurs in relation to multinational companies’ (MNCs) own employees, as stringent procedures tend to be in place to ensure good working practices. However, forced labour can be found even just one step removed, as contractors (especially those hired by or working for labour agencies) and employees of service suppliers (e.g. cleaning, logistics, construction) are at risk of exploitation even in OECD countries. The risk increases further down the supply chain, especially when companies source from countries with high poverty, inequality rates, a large informal economy, corruption, a lack of legal protection, poor law enforcement and/or where it is common practice to use recruitment agencies and labour providers that may not be registered or are poorly regulated.

Prevalence of Forced Labour

Forced labour is a truly global problem. Whilst there is a higher prevalence in the Global South, it is also present in the Global North, particularly amongst migrant and other vulnerable workers. While most global companies will take steps to ensure that they are not directly employing forced labour, they may be linked to such practices through their business relationships, including agency workers, contractors or suppliers.

2022 data from the ILO indicates that:

- 49.6 million people were living in modern slavery in 2021, of which 27.6 million were in forced labour and 22 million in forced marriage.

- Most cases of forced labour (86 per cent) are found in the private sector. Of the 27.6 million people in forced labour, 17.3 million are exploited in the private sector; 6.3 million in forced commercial sexual exploitation, and 3.9 million in forced labour imposed by state.

- Women and girls account for 4.9 million of those in forced commercial sexual exploitation, and for 6 million of those in forced labour in other economic sectors.

- Almost one in eight of all those in forced labour are children (3.3 million). More than half of these children are in commercial sexual exploitation.

- The Asia and the Pacific region has the highest number of people in forced labour (15.1 million) and the Arab States the highest prevalence (5.3 per thousand people).

- Migrant workers are more than three times more likely to be in forced labour than non-migrant adult workers.

The Global Slavery Index has been developed by the Walk Free Foundation, the ILO and the International Organisation for Migration (IOM). Their 2023 report highlights several key trends. The prevalence of modern slavery in high-GDP countries is higher than previously understood. This underscores that even in countries with seemingly strong legislation against modern slavery, such as G20 countries, there continue to be critical gaps in the protection of vulnerable groups.

There has been an increase in the severity and frequency of labour rights violations in key Asian manufacturing hubs over the last few years (Verisk Maplecroft).

Forced labour risks have increased as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. As millions of workers have been left without an income due to the pandemic, and without any savings or social protection to fall back on, this increases the pool of workers vulnerable to debt bondage and other forms of forced labour (ILO).

Reports of forced labour in the Xinjiang region of China have resulted in multiple countries escalating pressure against the Chinese Government. The US has passed the Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act (UFLPA), which creates a rebuttable presumption that all goods made in whole or in part in Xinjiang are made with forced labour and thus denied entry into the US. The EU has also announced a forced labour ban, which applies globally but which is also likely to use risk-based enforcement to target products from Xinjiang. The US, UK, the European Union and Canada have also imposed sanctions on officials in China over human rights abuses against Uyghur and other Muslim minorities. These measures by multiple Governments are likely to have wide-ranging implications for companies across multiple sectors, with cotton, polysilicon, tomatoes all likely to be impacted. Moreover, several key elements required to power the transition to green energy are impacted, with the majority of the world’s solar PV supply chains linked to China in general and Xinjiang in particular. (Also see paragraph 78 of the ILO’s Application of International Labour Standards 2021 report.)

In March 2021, fifty countries have shown their commitment to eradicate modern slavery by ratifying the ILO Forced Labour Protocol (P29). The ratifications have met an initial target set by the 50 for Freedom campaign, led by the ILO, International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) and the International Organisation of Employers (IOE), which urges Governments to take action on forced labour.

Target 8.7 of the Sustainable Development Goals sets out the ambition to end all forms of forced labour by 2030. Alliance 8.7, a multi-stakeholder partnership created in 2016, seeks to support the achievement of Target 8.7 through encouraging the alignment of global, regional and national efforts, and through sharing knowledge and driving innovation.

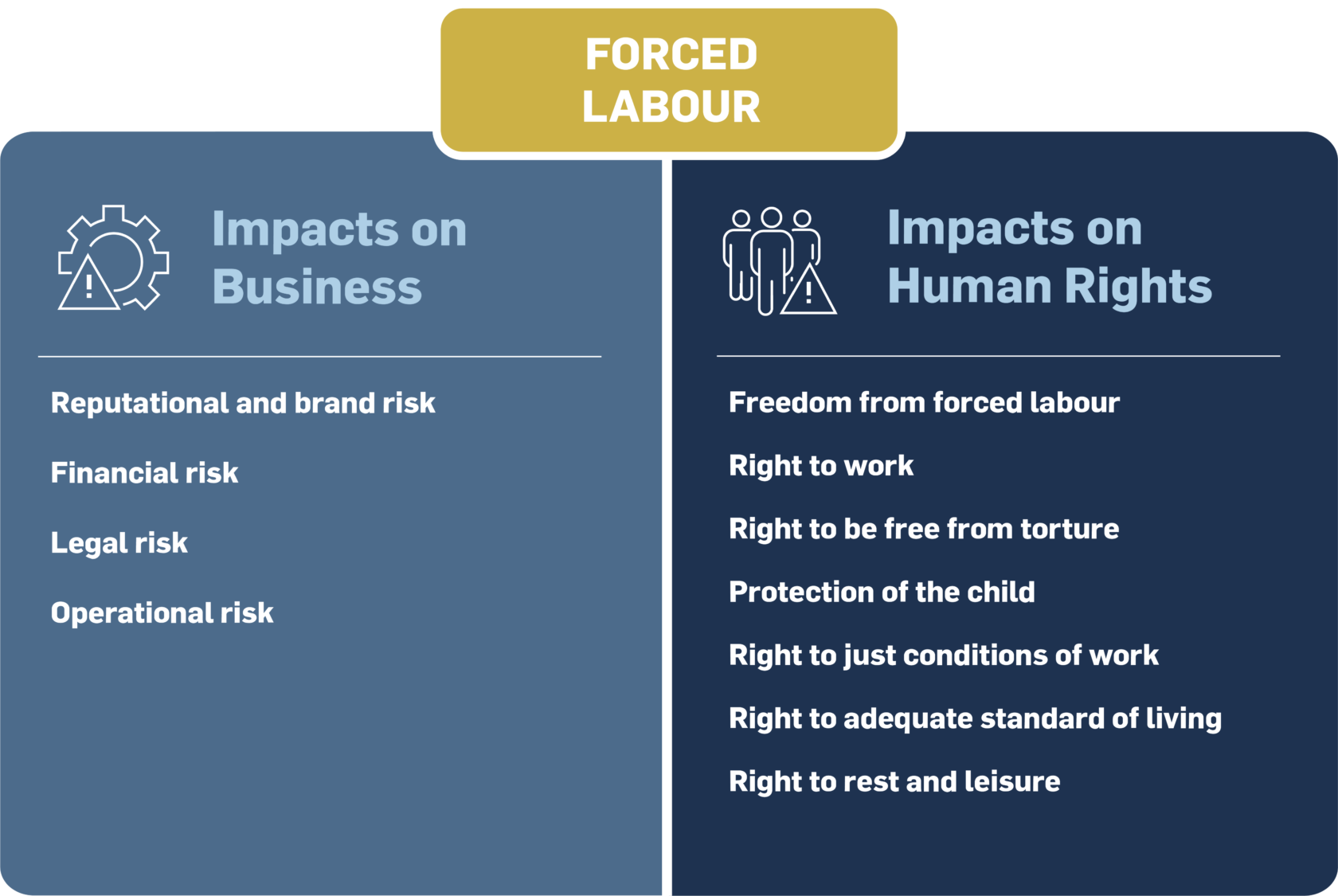

Impacts on Businesses

Businesses can be impacted by forced labour risks in their operations and supply chains in multiple ways:

- Reputational and brand risk: Campaigns by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), trade unions, consumers and other stakeholders against MNCs can result in reduced sales and brand erosion. This can also hurt employee retention and make a company less attractive to potential employees.

- Financial risk: Consumer boycotts against companies that are alleged or found to have forced labour in their supply chain can result in reduced sales. Divestment, avoidance or increased costs of finance by investors and finance providers (many of which are increasingly applying environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria to their decision-making) can result in reduced or more expensive access to capital and reduced shareholder value.

- Legal risk: Modern slavery legislation, which may include mandatory due diligence and reporting, increases compliance risks as there may be a risk of significant penalties in the event of failure to meet these obligations. Several European countries and the EU itself have passed or are passing consequential, extra-territorial legislation targeting forced labour in global value chains. This increases the legal risks for offending companies who fail to ensure that their operations and value chains are slavery free. Such failures also carry with them additional financial and operational risks as a result of operational and supply chain disruption.

- Operational risk: Changes to companies’ supply chains made in response to the discovery of forced labour may result in disruption. For example, companies may feel the need to terminate supplier contracts (resulting in potentially higher costs and/or operational disruption) and direct sourcing activities to lower-risk locations. Additionally, internal resources will need to be dedicated to address any allegations, requiring commitment across the management and relevant teams. This is particularly the case if the company has not established proper due diligence procedures and systems.

Impacts on Human Rights

Forced labour has the potential to impact a range of human rights,[2] including but not limited to:

- Right to freedom from forced labour (UDHR, Article 4; ICCPR, Article 8): Freedom from forced labour is a human right in and of itself. Freedom from forced or compulsory labour is a cornerstone of the ILO’s “decent work” concept and one of the most basic human rights. The prohibition of the use of forced or compulsory labour in all its forms is considered now as a peremptory norm of international law on human rights; this means that it is of an absolutely binding nature from which no exception is permitted.

- Right to work (UDHR, Article 23; ICESCR, Article 6): The right to work is considered a fundamental right. One of its essential components is the right to free choice of employment. This implies the right of everyone not to be forced to engage in employment or to be abused or exploited in that employment.

- Right not to be subjected to torture, cruel, inhuman and/or degrading treatment or punishment (ICCPR, Article 7): By its very nature, forced labour often involves the use of degrading treatment and the “menace of penalty” forcing people to work. For example, security forces may be employed to use abusive practices or threats to coerce people into undertaking forced labour.

- Rights of protection of the child (ICESR Article 10): Forced labour may involve entire families working to pay off a debt, or families of migrant workers denied remittances as a result of excessive recruitment fees or wage theft. Children may also be trafficked for the purpose of forced labour.

- Right to enjoy just and favourable conditions of work (UDHR, Article 23; ICESCR, Article 7): People working under conditions of forced labour regularly work excessive hours, often for little or no pay. They are also often forced to work under dangerous and unsafe conditions. Due to the very circumstances in which they are employed, their working conditions are unlikely to be just or favourable.

- Right to an adequate standard of living (including access to adequate food, clothing, housing and water) (ICESCR, Article 11): Workers who are victims of forced labour often encounter limited access to adequate food, clothing, housing and living conditions (including water and sanitation). This is particularly the case as workers are often kept in closed facilities subject to the control of the owners of the facility who may show little regard for their well-being.

- Right to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay (UDHR, Article 24): Given the nature of forced labour, workers who are coerced into employment are often denied access to rest and leisure.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The following SDG targets relate to forced labour:

- Goal 5 (“Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”), Target 5.2: Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation

- Goal 8 (“Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all”), Target 8.7: Take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labour, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms

Key Resources

The following resources provide further information on how businesses can address forced labour responsibly in their operations and supply chains:

- ILO, Combating Forced Labour: A Handbook For Employers and Business: This guidance provides materials and tools for employers and business to strengthen their capacity to address the risk of forced labour and human trafficking in their own operations and in global supply chains.

- UN.GIFT, Human Trafficking and Business: Good Practices to Prevent and Combat Human Trafficking: A resource developed by the UN Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking and other stakeholders that explains what companies can do to take action against human trafficking. The guide provides a series of case studies that highlight the practical actions companies are taking to fight human trafficking.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Base Code Guidance: Modern Slavery: A step-by-step guide for businesses on eliminating forced labour in global supply chains.

- British Standards Institute (BSI), BS:25700: Organisational Responses to Modern Slavery: This document provides a range of practical support for businesses looking to combat modern slavery and forced labour in their operations and supply chains.

Definition & Legal Instruments

Definition

The term “forced labour” is defined in the ILO Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29) as any work or service that is exacted from any person under the menace or threat of a penalty, and which the person has not entered into of their own free will. Three elements of forced or compulsory labour are considered below:

- Work or service should be distinguished from “education or training”. The principle of compulsory education is recognized in various international instruments as a means of securing the right to education. This includes a compulsory scheme of vocational training, which does not constitute forced labour. With regards to work or service, this includes all types of work and employment, regardless of the industry or sector within which it is found, including the informal sector.

- Threat of penalty should be understood in a broad sense. It covers penal sanctions, as well as various forms of coercion, such as arrest or jail, refusal to pay wages or forbidding a worker from travelling freely. Threats of retaliation can take different forms, including the threat or use of violence, physical obligations or even death threats, to psychological threats, such as denouncing an illegal worker to the authorities. The penalty might also take the form of a loss of rights or privileges.

- Work or service is undertaken involuntarily. Involuntariness refers to the notion of consent, which is the key element. Free and informed consent must exist throughout the labour relationship and the worker must be able to withdraw their consent at any time. Involuntary work involves external and indirect pressures, such as partially withholding a worker’s salary as a condition of a loan repayment, the absence of wages or remuneration, or the seizure of the worker’s identity documents. Workers may also find themselves in the situation of forced labour because of fraudulent, deceptive employment practices, where workers (often migrant) are hired for a specific job and terms (voluntarily) but are then forced to do a different job, under exploitative conditions (involuntarily).

The hidden nature of forced labour and its many forms can add to the difficulty that companies face in addressing this issue. Forced labour can take several different forms, including the following:

- Debt bondage, which occurs where a worker is either forced to work for little or nothing in order to repay a debt (either their own debt or that of another) or is forced into debt in order to access work. The former is straightforwardly understood as a matter of forced labour, the latter may not be so obvious. It is common in some parts of the world for recruitment agents to charge migrant workers large fees in order to obtain work overseas. These fees are often set at illegally high levels and are a form of extortion of already vulnerable people. The issue of excessive recruitment fees has received considerable focus in the last 10-15 years and it is now a recognised marker of modern slavery. In some countries and for some roles, fees can be more than $5,000. Most workers cannot afford to pay such fees from their own or their family’s resources so they may take on debt from informal money lenders at high rates of interest. The resulting fees and interest payments can take a large percentage of the worker’s pay for months or years into their employment.

- This form of debt bondage also acts as a lever to facilitate further labour rights abuses, such as wage theft, contract substitution, poor housing and physical or sexual abuse as the worker cannot afford to lose their job and risk defaulting on their loan. The ‘employer pays’ model has been promoted by the ILO and others to ensure that the costs of recruitment and deployment are absorbed by employers, so that migrant and other vulnerable workers are not forced into debt during their search for work. See the IHRB ‘Employer Pays’ campaign for more information.

- Compulsory work occurs where people are legally required, often by the Government, to work on certain projects, and it is prohibited under the ILO Convention No. 105. This includes the use of forced labour as a punishment for the expression of political views, for the purposes of economic development, as a means of labour discipline, as a punishment for participation in strikes and as a means of racial, religious or other discrimination.

- Prison labour constitutes forced labour when undertaken for private entities without the free and informed consent of the prisoner and when the conditions of work do not approximate those of a free labour relationship. For instance, prisoners engaging in such work receive little or no compensation or are unable to withdraw their consent at any time. ILO Convention No. 105 prohibits the use of compulsory prison labour. Individuals in this category may include prisoners of conscience or prisoners being “re-educated” to manufacture garments or components for electronic goods.

- Human trafficking occurs when people are moved from one location to another (often across borders) to be exploited either sexually or for their labour. Once they are away from their families and support networks, victims are highly vulnerable and may find themselves forced to work in conditions to which they had not consented or working in a completely different job or with altered contract terms.

According to the ILO, indicators that can help identify persons who are possibly trapped in a forced labour situation and who may require urgent assistance include:

- Abuse of vulnerability

- Deception

- Restriction of movement

- Isolation

- Physical and sexual violence

- Intimidation and threats

- Retention of identity documents

- Withholding of wages

- Debt bondage

- Abusive working and living conditions

- Excessive overtime

The presence of a single indicator in a given situation may in some cases imply the existence of forced labour. However, in other cases, businesses may need to look for several indicators which, taken together, point to a forced labour case.

Legal Instruments

ILO Conventions

Two ILO conventions and one protocol form the international legal framework on the prohibition of forced labour and are used by most countries as guidance to their own national laws. These instruments define the conditions and circumstances that amount to forced labour and serve as a point of reference for national legislation that conforms to international standards. The elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour is one of the ILO’s five fundamental rights and principles at work, which member states have to promote regardless of whether they have ratified the respective conventions.

- ILO Forced Labour Convention, No. 29 (1930): The convention sets the general obligation to suppress the use of forced labour in all its forms and provides the definition of forced labour.

- ILO Convention on the Abolition of Forced Labour, No. 105 (1957): The convention prohibits certain forms of forced labour that were allowed under the ILO Convention No. 29, including punishment for strikes and holding particular political views.

- ILO Protocol of 2014 to the Forced Labour Convention, No. 29 (2014): The Protocol supplements Convention No. 29 to address implementation gaps to effectively eradicate forced labour.

In March 2021, the 50 for Freedom campaign, led by the ILO, ITUC and IOE, met its goal of having 50 countries ratify the Protocol. The Protocol encourages Governments to support due diligence by public and private sectors to prevent forced labour. The Protocol is of particular relevance for businesses since it contains specific provisions referring to enterprises and employers. For example, Article 2 on prevention measures refers to:

- “Educating and informing employers, in order to prevent their becoming involved in forced or compulsory labour practices”; and

- “Supporting due diligence by both the public and private sectors to prevent and respond to risks of forced or compulsory labour”.

ILO instruments on forced labour are almost universally ratified. The ILO supervisory bodies, especially the Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations (CEACR) and the Committee on the Application of Standards (CAS), regularly assess the manner in which ratifying States implement their obligations under these conventions.

However, ratification does not guarantee that these countries are free from forced labour, as the existence and enforcement of national laws to address forced labour varies. In due diligence, it is, therefore, important to check the ratification status for particular countries as an indicator of potentially more limited state protections against forced labour.

The fight against forced labour is included as one of the Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact: “Principle 4: Businesses should uphold the elimination of all forms of forced and compulsory labour”. The four labour principles of the UN Global Compact are derived from the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work.

These fundamental principles and rights at work have been affirmed and developed in the form of specific rights and obligations in International Labour Conventions and Recommendations and cover issues related to child labour, discrimination at work, forced labour and freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining.

Member States of the ILO have an obligation to promote the effective abolition of forced labour, even if they have not ratified the Conventions in question.

Gaps in National Laws

A 2018 ILO review found that a total of 135 countries have laws that define, criminalize and assign penalties for forced labour, but in the remaining countries, the issue of forced labour is covered only partially or not at all. In addition, where laws against forced labour exist, they have not kept pace with recent mutations of forced labour linked to trafficking, recruitment debt and other developments. Although national laws defining and criminalizing forced labour are essential, many countries with advanced forced labour laws still have forced labour issues.

Other Legal Instruments

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) set the global standard regarding the responsibility of business to respect human rights in their operations and across their value chains. The Guiding Principles call upon States to consider a smart mix of measures — national and international, mandatory and voluntary — to foster business respect for human rights.

The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises are also a useful and authoritative source of human rights and sustainability best practice for organisations. They were updated in 2023 to respond to urgent social, environmental and technological issues businesses and societies are facing.

Domestic Legislation

Companies are increasingly subject to non-financial reporting and due diligence obligations in the jurisdictions in which they operate, which often include disclosures on their performance. There are several high-profile examples of national legislation that specifically mandate human rights-related reporting and other positive legal duties, including the United Kingdom Modern Slavery Act 2015, Australian Modern Slavery Act 2018, the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act 2010, the French Corporate Duty of Vigilance Law 2017, German Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains 2021 and the Norwegian Transparency Act 2022.

Also, in 2021 the Netherlands submitted a Bill for Responsible and Sustainable International Business Conduct, and the European Commission announced its Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). This Directive is likely to come into force between 2025 and 2027 and will make human rights and environmental due diligence mandatory for larger companies.

In September 2022 the EU Commission also announced the introduction of a Forced Labour Ban, which aims to ensure that products made with forced labour are kept out of the EU single market. These mandatory due diligence and disclosure laws require companies to publicly communicate their efforts to address actual and potential human rights impacts, including forced labour. Failure to comply with these obligations could involve significant legal risk for companies.

Contextual Risk Factors

The prevention of forced labour requires an understanding of its underlying causes and the consideration of a wide range of issues, from poor legal protections to restriction of movement.

Key risk factors include:

- Inadequate legal framework offering a poor standard of legal protection against forced labour. A lack of strong laws against forced labour or inadequate criminal sanctions can result in a lack of deterrence.

- Poor enforcement of domestic labour laws as a result of inadequate training, an under-resourced labour inspectorate or high levels of corruption.

- High levels of poverty, inequality and unemployment, particularly in countries where the informal economy constitutes a high percentage of the overall workforce. Where there is a lack of State support or formal contracts enshrining workplace rights, workers face greater vulnerability to poor working conditions that may amount to forced labour.

- High levels of migration, particularly of low-skilled and low-paid labour, exacerbates the likelihood of forced labour and other labour rights violations (see Migrant Workers issue). Migrants make up a much larger proportion of those subject to forced labour in specific sectors and locations. Undocumented migrants or those who have their legal employment status tied to their employer under sponsorship visa programmes may be unwilling to report labour rights violations or may be unable to leave or return home without the explicit permission of the sponsor.

- Lack of understanding of what constitutes forced labour among workers. Migrant workers, in particular those who may not speak the local language or be aware of their rights under the law, are more vulnerable to exploitation by third-party agencies or employers. This puts them at a greater risk of practices that could constitute conditions amounting to forced labour, such as being subject to excessive recruitment fees or having their identity documents retained.

- The use of recruitment agencies and other labour intermediaries raises the risk of labour rights violations. The most common violation is the charging of excessively high recruitment fees that leave migrant workers in substantial debt leading to conditions amounting to forced labour or debt bondage.

- Unskilled or low-skilled work where the barriers to entry are low may lead to a higher risk of exposure to forced labour. This includes what is often known as “3D”, or “dirty, difficult and dangerous” jobs. Industries that have low barriers to entry may be at a greater risk of trafficking. While low wages are not necessarily linked to trafficking, pressure to keep labour costs low creates a “race to the bottom”, which in turn may be associated with exploitative working conditions that amount to forced labour.

Industry-specific Risk Factors

While forced labour is present in many industries, the 2022 ILO report suggests that the sectors where it is most prevalent include; services, construction, agriculture, domestic work and manufacturing. To identify potential forced labour risks for other industries, companies can access the CSR Risk Check.

Construction

The construction industry is estimated to be responsible for 16.3% of identified forced labour exploitation cases as of 2022 (ILO). Male victims make up most cases in the construction industry, at 86%. Construction is a rapidly growing industry, and the proliferation of third-party recruitment agencies increases the risk of workers, the majority of whom are migrants, to excessive recruitment fees. High levels of debt to such agencies leave workers in a position of debt bondage. For example, migrant workers in the United Arab Emirates are reported to have paid more than five months of wages in recruitment fees.

Construction-specific risk factors include the following:

- Dangerous working conditions: Working conditions are notoriously demanding and dangerous, with high levels of industrial accidents. Workers employed under forced labour conditions are more vulnerable to being coerced into working in unsafe conditions that disregard occupational safety and health.

- Project complexity: The complexity of construction projects exacerbates the risks of workers being subject to late or non-payment of wages, thus increasing their vulnerability and opportunity for abuse. Construction projects may involve hundreds of subcontractors, including labour agencies, with frequently changing workers. In many instances, contractors are not obliged to pay subcontractors until they have received payment from the client.

- Remote worksites: Construction worksites may be remote or difficult to reach, which puts workers under greater control of their employers. Workers may face greater restrictions on movement and may be unable to seek assistance if they are subject to forced labour.

Helpful Resources

The following resources provide further information on how businesses can address forced labour responsibly in their operations and supply chains:

- ILO, Migrant Work & Employment in the Construction Sector: This resource looks at some of the barriers migrant workers can face in accessing fair, safe and decent work in the construction sector. It includes recommendations for employers on how to ensure better working conditions for migrant workers.

- Business and Human Rights Resource Centre, A Human Rights Primer for Business: Understanding Risks to Construction Workers in the Middle East: This resource provides specific regional advice for construction companies operating in the Middle East for key human rights risks to look out for, with a focus on labour rights issues faced by migrant workers.

- Stronger Together: Stronger Together has developed a Construction Programme with resources aimed at tackling modern slavery in the construction industry. This includes a specialist training workshop and a best practice toolkit.

- LexisNexis, Hidden in Plain Sight: Modern Slavery in the Construction Industry: This guidance provides key elements that construction companies must consider in tackling modern slavery.

- Chartered Institute of Building, Construction and the Modern Slavery Act: Tackling Exploitation in the UK: This guidance provides detailed advice on how construction companies can successfully meet the mandatory reporting requirements under the UK Modern Slavery Act. It also gives practical advice on how companies can detect, support and remediate cases of modern slavery.

Electronics Manufacturing

The electronics manufacturing industry poses forced labour risks, with major electronics, telecommunications and technology brands facing forced labour allegations. The 2022 findings of a benchmarking report by KnowTheChain found that despite increased profits during the pandemic, the vast majority of ICT companies scored poorly in their efforts to address labour rights abuses in their supply chains. Companies received a median score of just 14/100, demonstrating the continued poor progress shown in previous years’ reports.

Industry-specific risk factors include the following:

- China and Malaysia: The US Department of Labor’s 2022 report suggests that electronics produced in China and Malaysia have been found to be linked to forced labour. Migrant workers, particularly in Malaysia, are subject to excessive recruitment fees, which often plunge them into debt bondage even before the start of employment.

- Job competition: Competition for jobs in the industry can be strong, particularly with respect to famous brands. This can result in workers working excessive hours without adequate rest. Combined with underpayment or non-payment of already low wages and excessive recruitment fees, workers may find themselves in working conditions amounting to debt bondage or forced labour.

- Internships: Student workers are given compulsory placements in electronics manufacturing factories, modelled as “internships,” where they are forced to work excessive hours and often go unpaid or earn extremely low wages.

- Mineral supply chains: Electronics companies may be linked to forced labour via their mineral supply chains given that some of the minerals and metals used to manufacture electronic components carry forced labour risks (i.e. during the mining process) — see the section on mining.

Helpful Resources

- Responsible Business Alliance (RBA), Student Workers Management Toolkit: This toolkit helps human resources and other managers support responsible recruitment and management of student workers in electronics manufacturing.

- Responsible Minerals Initiative, Material Change: A Study of Risks and Opportunities for Collective Action in the Materials Supply Chains of the Automotive and Electronics Industries: This report examines responsible sourcing of materials in the automotive and electronics industries, including association with forced labour.

- OECD, Due Diligence Guidance in the Electronics Sector: This short guidance summarizes other OECD tools that are relevant for businesses operating in the electronics sector.

Fashion and Apparel

The fashion and apparel industry has had many documented cases of forced labour, particularly in the manufacturing stages. An increasing reliance on workers performing precarious work in the industry puts vulnerable groups such as migrant workers and women at greater risk of labour rights violations, including forced labour. 2021 findings from KnowTheChain’s benchmarking report for the apparel and footwear industry show that despite some improvements in previous years, companies’ efforts to address forced labour in their supply chains were hampered by the COVID-19 pandemic. The report found that the average benchmark score of the global apparel companies assessed was 41/100, with luxury brands performing the worst, demonstrating significant gaps that continue to exist in company efforts to combat forced labour.

Fashion and apparel specific risk factors include the following:

- Tracing difficulties: This industry features a lot of outsourcing, subcontracting and homeworking, making tracing where a product was made and by whom difficult. A joint ILO-OECD report states that outsourcing, particularly when it is unauthorized, can increase risks of forced labour and human trafficking as it involves informal labour that can remain off the radar of auditors or labour inspectors.

- Labour market intermediaries: Outsourcing can also involve the use of labour market intermediaries who themselves subcontract further, thus making informal labour in supply chains more opaque. The use of subcontractors, especially informal ones, increases the risk of forced labour, as they may charge workers excessive recruitment fees, which could subject workers to debt bondage. Workers may also face restrictions on mobility, illegal wage deductions and threats of penalty under subcontractors or labour intermediaries.

- Delivery times: Pressure around delivery times in the apparel sector is another potential driver of labour rights violations. According to a joint ILO-OECD report, suppliers seeking to cope with time pressures may turn to outsourced labour, overtime and/or the use of informal labour contracting, which in turn increases the risks of labour rights violations, including forced labour.

- Cotton production: Beyond textile and manufacturing value chains, forced labour risks are also present in cotton production. Although much progress has been made in the last decade in ending systemic forced labour in cotton production, state-sponsored forced labour in the cotton industry still exists.

Helpful Resources

- OECD, Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains in the Garment & Footwear Sector: This guidance aims to help fashion and apparel businesses implement the due diligence recommendations contained in the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises in order to avoid and address the potential negative impacts of their activities and supply chains on a range of human rights, including forced labour.

- ILO, Guide for Employers on Preventing Forced Labour in the Textile and Garment Supply Chains in Viet Nam: This guide was jointly developed by the Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry (VCCI) and the ILO to serve as a reference point for company managers and staff responsible for human resources management and social and legal compliance issues in Vietnamese textile and garment enterprises.

- ILO, 2020 Third-Party Monitoring of Child Labour and Forced Labour During the Cotton Harvest in Uzbekistan: This report publishes the latest ILO findings on the progress in eradicating forced labour and child labour in Uzbekistan.

- The Know the Chain: Apparel and Footwear Benchmark Report 2021: This report analyzes how apparel companies responded to increased risks of forced labour during the COVID-19 pandemic and finds that the 37 largest global companies fail to stand up for workers who face exploitation.

- SOMO, Spinning Around Workers’ Rights: International Companies Linked to Forced Labour in Tamil Nadu Spinning Mills: This report uses the 11 indicators for forced labour developed by the ILO to assess the working and living conditions of spinning mill workers in Tamil Nadu. Of the 11 indicators, five were found to be most relevant: abuse of vulnerability; deception; intimidation and threats; abusive working and living conditions; and excessive overtime.

- Anti-Slavery International, Sitting on Pins and Needles: A Rapid Assessment of Labour Conditions in Vietnam’s Garment Sector: This report assesses labour conditions in Vietnam’s garment sector and finds that there is a significant risk of forced labour in this industry.

- Clean Clothes Campaign, Labour Without Liberty: Female Migrant Workers in Bangalore’s Garment Industry: This report finds that female migrants employed in India’s garment factories that supply to big international brands are often recruited with false promises about wages and benefits and subject to conditions of modern slavery.

- Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), An Investor Briefing on the Apparel Industry: Moving the Needle on Labour Practices: This resource guides institutional investors on how to identify negative human rights impacts in the apparel industry, including those pertaining to forced labour.

Agriculture and Fishing

According to the 2022 ILO report, an estimated 12.3% of forced labour exploitation cases can be found in the agriculture and fishing sectors. Male victims outnumber female victims by more than twice, at 68%, compared to 32% of women. The most severe cases of forced labour in the fishing sector have resulted in physical brutality and even loss of life, as has been documented in a report of forced labour on deep-sea fishing vessels in the Asian region. The US Department of Labor’s 2020 report suggests that the most common items produced by forced labour in agriculture and fishing include cotton, sugarcane and seafood. Cocoa is another agricultural commodity that is often linked to forced labour risks.

Agriculture or fishing-specific risk factors include the following:

- Informal sector: Due to extremely high levels of informality in the agriculture and fishing sectors, workers are more vulnerable to underpayment, late payment or non-payment of wages, which may place them in situations amounting to debt bondage or forced labour.

- Cost cutting pressures: Pressure to cut costs in the agricultural sector is one of the key drivers of labour exploitation. Low prices received for agricultural produce can lead to workers experiencing underpayment and manipulation of wages. Workers may also face elements of forced labour, such as debt bondage, physical violence, threats, verbal or sexual abuse.

- Cotton production: State-orchestrated forced labour is prevalent in cotton production. Reports of state-imposed forced labour in Xinjiang (China) have put the spotlight on cotton and tomato production in the region. The elimination of forced and child labour in Uzbekistan is an example of how countries can demonstrate major progress through coordination and collaboration with international organizations such as the ILO and other civil society groups.

- Migrant workers: The agricultural sector traditionally relies heavily on migrant workers, who are more vulnerable to forced labour conditions through the withholding of passports and restriction of movement. They may also be more subject to excessive recruitment fees leading to conditions of debt bondage.

- Labour providers: A common feature of the agricultural sector is the presence of labour providers, such as employment or recruitment agencies. If such agents are unscrupulous or illegitimate, this can result in a range of abuses such as non-payment or late payment of wages, restriction on physical movement, violence and threats.

- Isolation: Fishing industry workers may be at sea for long periods, away from the reach of national labour inspection. Due to the isolation of the workplace, workers face restriction of movement and are unable to escape once a fishing vessel is at sea.

- Transhipment: The practice of transhipment — the act of offloading goods or containers from one ship and loading it onto another — increases the likelihood of forced labour. Transhipment activities are often illegal, involving the smuggling of criminal goods or human trafficking.

Helpful Resources

- OECD-FAO, Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains: This guidance provides a common framework to help agro-businesses and investors support sustainable development and identify and prevent forced labour.

- FAO, Regulating Labour and Safety Standards in the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Sectors: This resource provides information on international labour standards that apply in agriculture, including those on forced labour.

- ILO, Fishers First: Good Practices to End Labour Exploitation at Sea: This resource provides examples of good practices and innovative interventions from around the world aimed at eradicating forced labour and other forms of labour exploitation in the fishing industry.

- Fair Labor Association, ENABLE Training Toolkit on Addressing Child Labor and Forced Labor in Agricultural Supply Chains: The toolkit guides companies on supply chain mapping and forced labour in supply chains. It contains six training modules, a facilitator’s guide, presentation slides and a participant manual.

- PRI, From Farm to Table: Ensuring Fair Labour Practices in Agricultural Supply Chains: This resource provides guidelines on what investors should be looking for from companies to eliminate labour abuses in their agricultural supply chains.

- Sustainable Agriculture Initiative (SAI) Platform: The SAI Platform guidance document on forced labour facilitates the development of their members’ policies on forced labour.

- Stronger Together, Tackling Forced Labour in Agri-Businesses Toolkit: A comprehensive toolkit for agro-businesses to inform, equip and resource them to tackle forced labour. Includes practical advice on the specific steps to take across different areas of the businesses to effectively deter, detect and deal with forced labour.

- Fairtrade International, Guide for Smallholder Farmer Organisations – Implementing Human Rights and Environmental Due Diligence (HREDD): This guidance was developed to provide advice and tools on HREDD for farmer organisations to implement.

Hospitality

The hospitality sector is linked to significant forced labour risks, with the ILO estimating that 32% of forced labour cases sit within the “services” category, which includes hospitality (in the 2017 report, hospitality described as “accommodation and food service activities”).

Much of the hospitality sector relies on the outsourcing of services, such as cleaning, maintenance and security. Workers who are recruited by outsourcing methods, such as through subcontractors or third-party labour suppliers, often lack social protections and face wage discrimination, exacerbating forced labour risks.

Helpful Resources

- SILO, Guidelines on Decent Work and Socially Responsible Tourism: These guidelines provide practical information for developing and implementing policies and programmes to promote sustainable tourism and strengthen labour protection, including anti-forced labour measures.

- The Know How Guide, Human Rights and the Hotel Industry by the International Tourism Partnership: This guide provides an overview of human rights (including forced labour) within hospitality, with guidance on developing a human rights policy, performing due diligence and addressing any adverse human rights impacts.

- Human Rights in Tourism, An Implementation Guideline for Tour Operators by the Roundtable Human Rights in Tourism e.V.: This guideline aims to assist tour operators in implementing the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and includes references to forced labour.

- Sustainable Hospitality Alliance, Risks of Modern Slavery in Labour Sourcing Training: This online training module is designed by and for the hotel industry to improve awareness of modern slavery and human rights risks in hotel operations, focusing on the recruitment of staff or contractors.

- Sustainable Hospitality Alliance, Guidelines for Checking Recruitment Agencies: This guidance helps hotels implement more responsible practices and reduce the risks of human trafficking in their supply chain. It focuses on performing the necessary checks and procedures when engaging private employment agencies to recruit workers.

Mining and the Extractive Industry

Forced labour takes place in parts of the artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) industry, which is largely informal and highly labour intensive. The mining of “conflict minerals” — tantalum, tin, tungsten and gold — and other minerals such as cobalt in particular has been linked to forced labour. The US Department of Labor’s 2022 report suggests that coal, granite, gravel, iron and diamonds are also linked to forced labour.

Forced labour is also present in oil and gas extraction and infrastructure development such as around the construction of pipelines and offshore installations.

Helpful Resources

- OECD, Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas: The OECD guidance identifies forced labour as a serious human rights abuse associated with the extraction, transport or trade of minerals. The guidance has Practical actions for companies to identify and address any forms of forced and compulsory labour in mineral supply chains and conduct related due diligence.

- Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC), Responsible Jewellery Council Standards Guidance: This guidance provides a suggested approach for RJC members to implement the mandatory requirements of the RJC Code of Practice (COP), including forced labour in mining operations.

- Responsible Minerals Initiative, Material Change: A Study of Risks and Opportunities for Collective Action in the Materials Supply Chains of the Automotive and Electronics Industries: This report examines responsible sourcing of materials in the automotive and electronics industries, including association with forced labour. Responsible Minerals Initiative also has other helpful resources for mining companies on various steps of human rights due diligence.

- International Organization for Migration (IOM), Remediation Guidelines for Victims of Exploitation in Extended Mineral Supply Chains: These guidelines provide concrete, operational guidance to downstream companies and their business partners to ensure victims of exploitation are adequately protected and assisted when harm has occurred.

- International Council on Mining & Metals (ICMM), Human Rights: A range of resources, including guidance, training materials and good practice case studies, on human rights in the mining and metals sector.

- Ipieca, Company and Supply Chain Labour Rights Toolkit: Ipieca, the global oil and gas association, has developed a series of practical guidance and tools to help companies effectively identify, prevent and mitigate labour rights risks within their operations and supply chains.

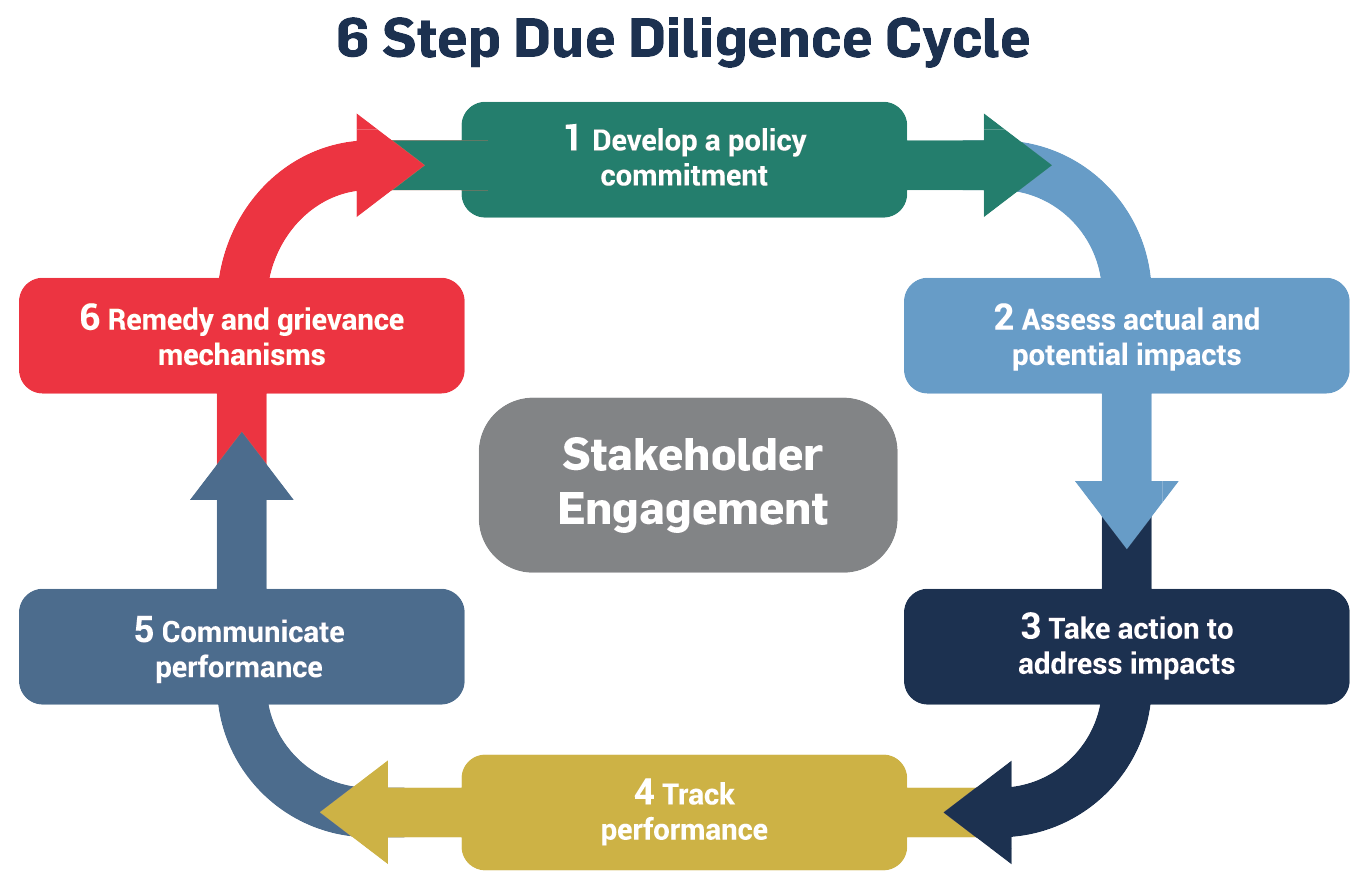

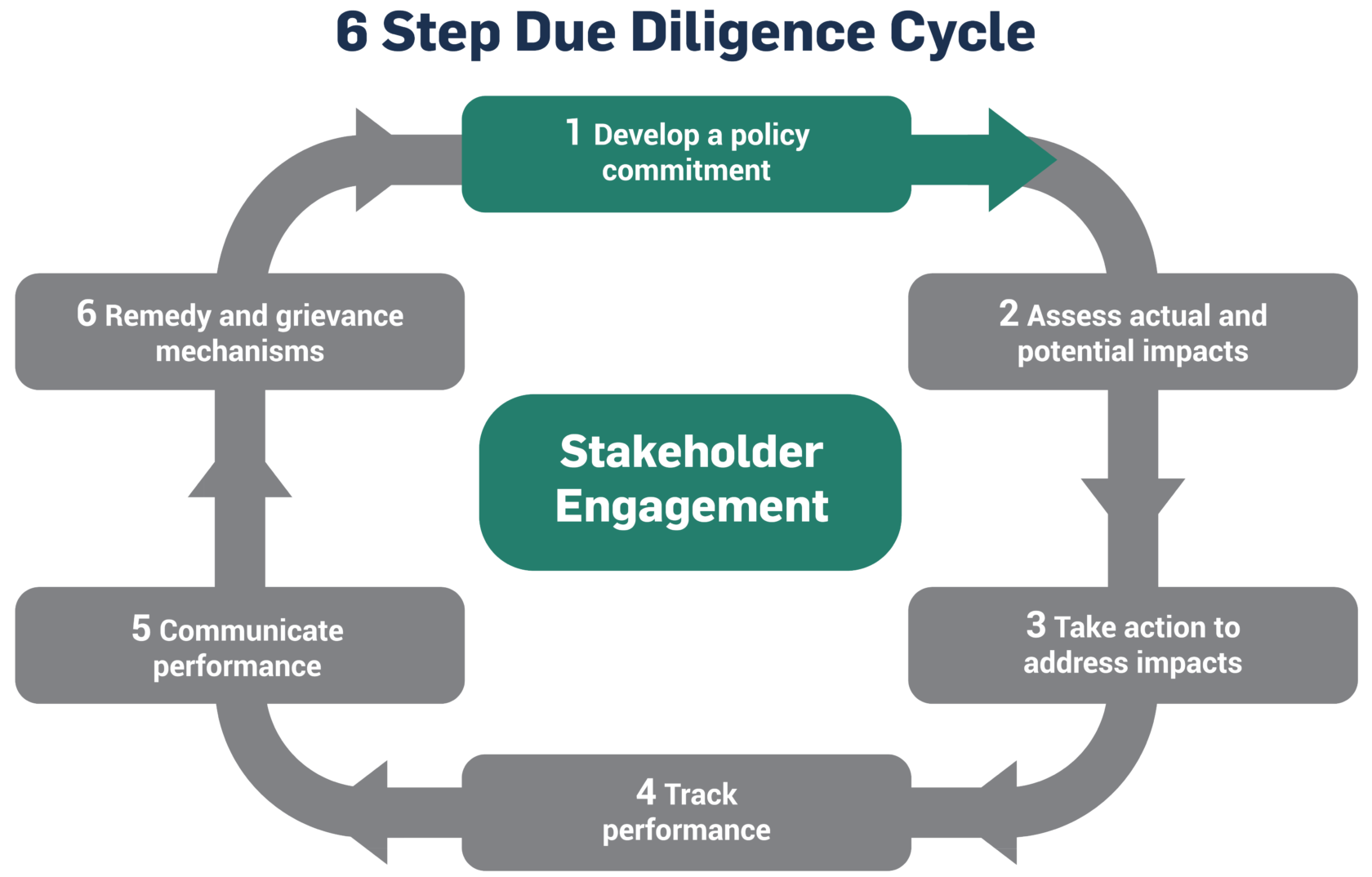

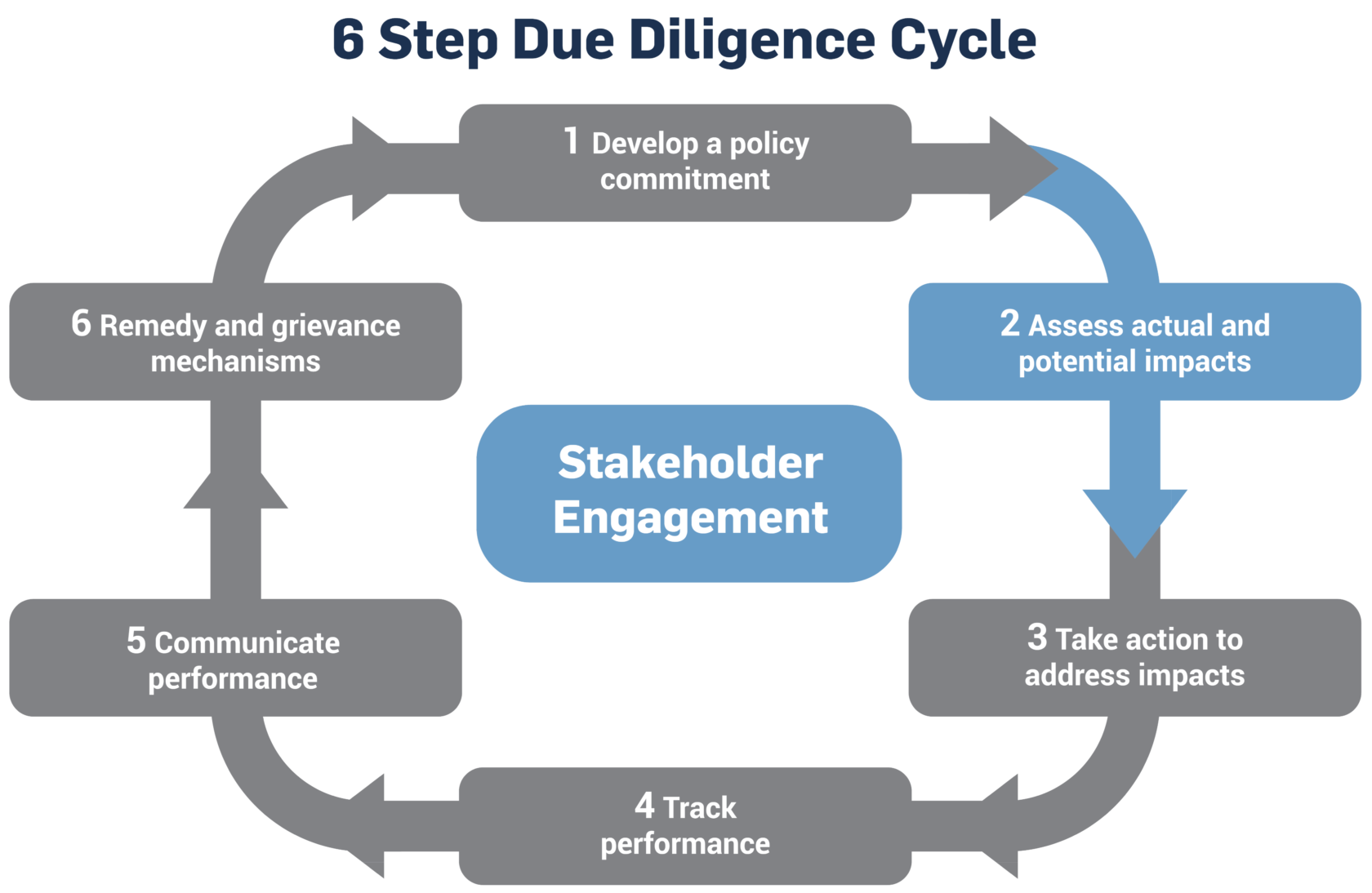

Due Diligence Considerations

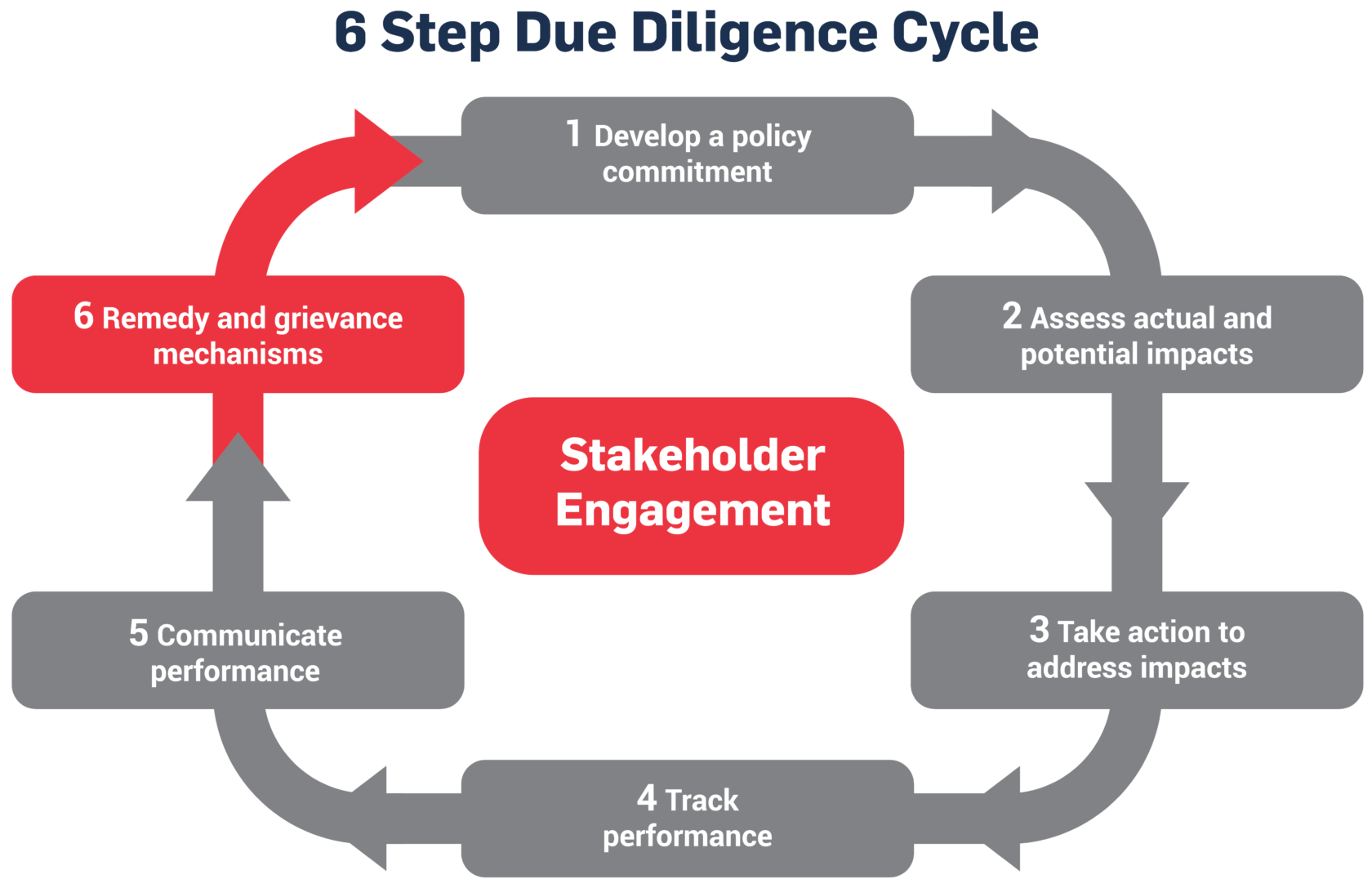

This section outlines due diligence steps that companies can take to eliminate forced labour in their operations and supply chains. The described due diligence steps are aligned with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). Further information on UNGPs is provided in the ‘Key Human Rights Due Diligence Frameworks’ section below or in the Introduction.

While the below steps provide guidance on forced labour in particular, it is generally more resource-efficient for companies to ‘streamline’ their human rights due diligence processes by also identifying and addressing other relevant human rights issues (e.g. child labour, discrimination, freedom of association) at the same time.

Key Human Rights Due Diligence Frameworks

Several human rights frameworks describe the due diligence steps that businesses should ideally implement to address human rights issues, including forced labour. The primary framework is the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). Launched in 2011, the UNGPs offer guidance on how to implement the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework, which establishes the respective responsibilities of Governments and businesses — and where they intersect.

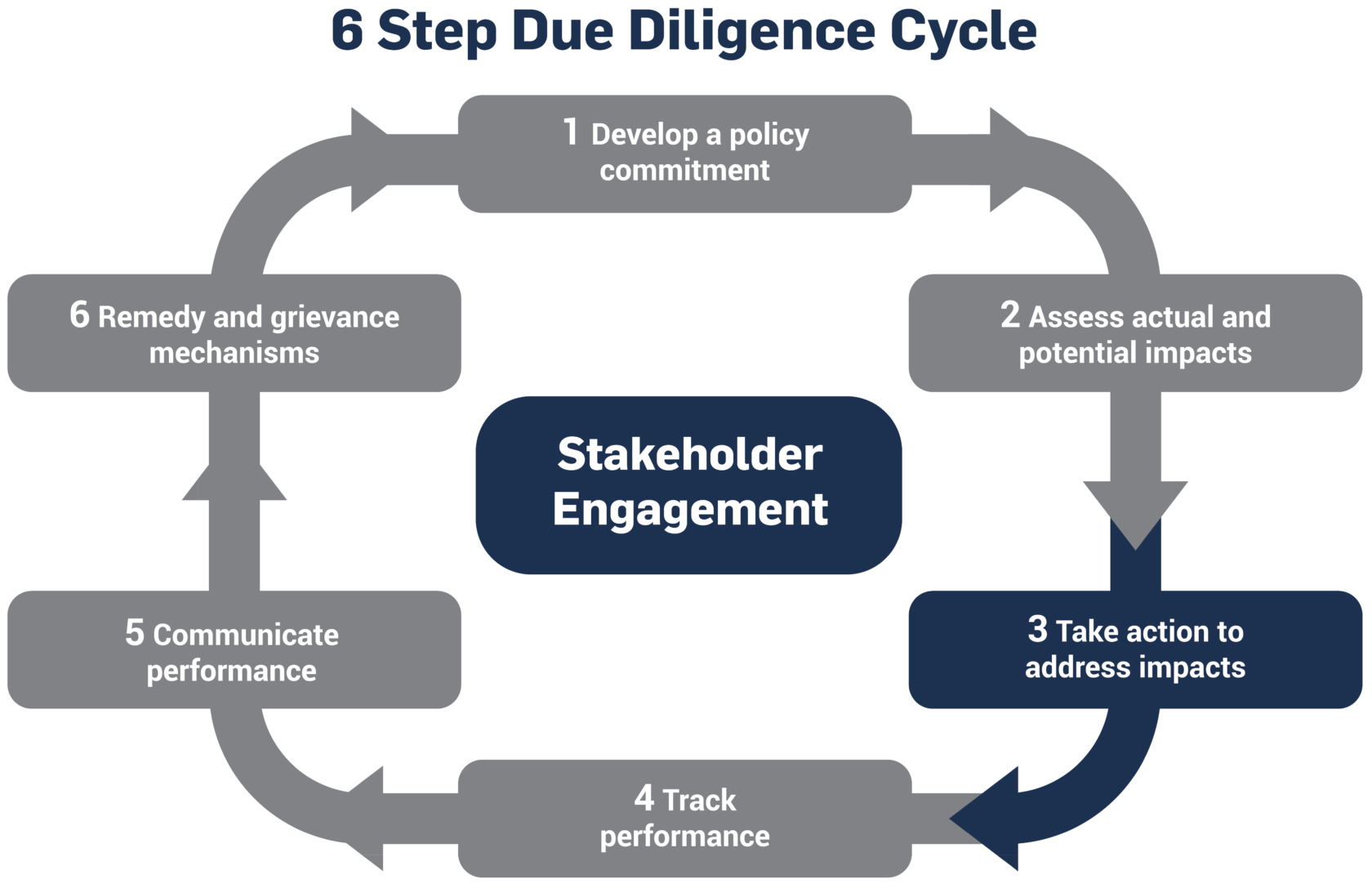

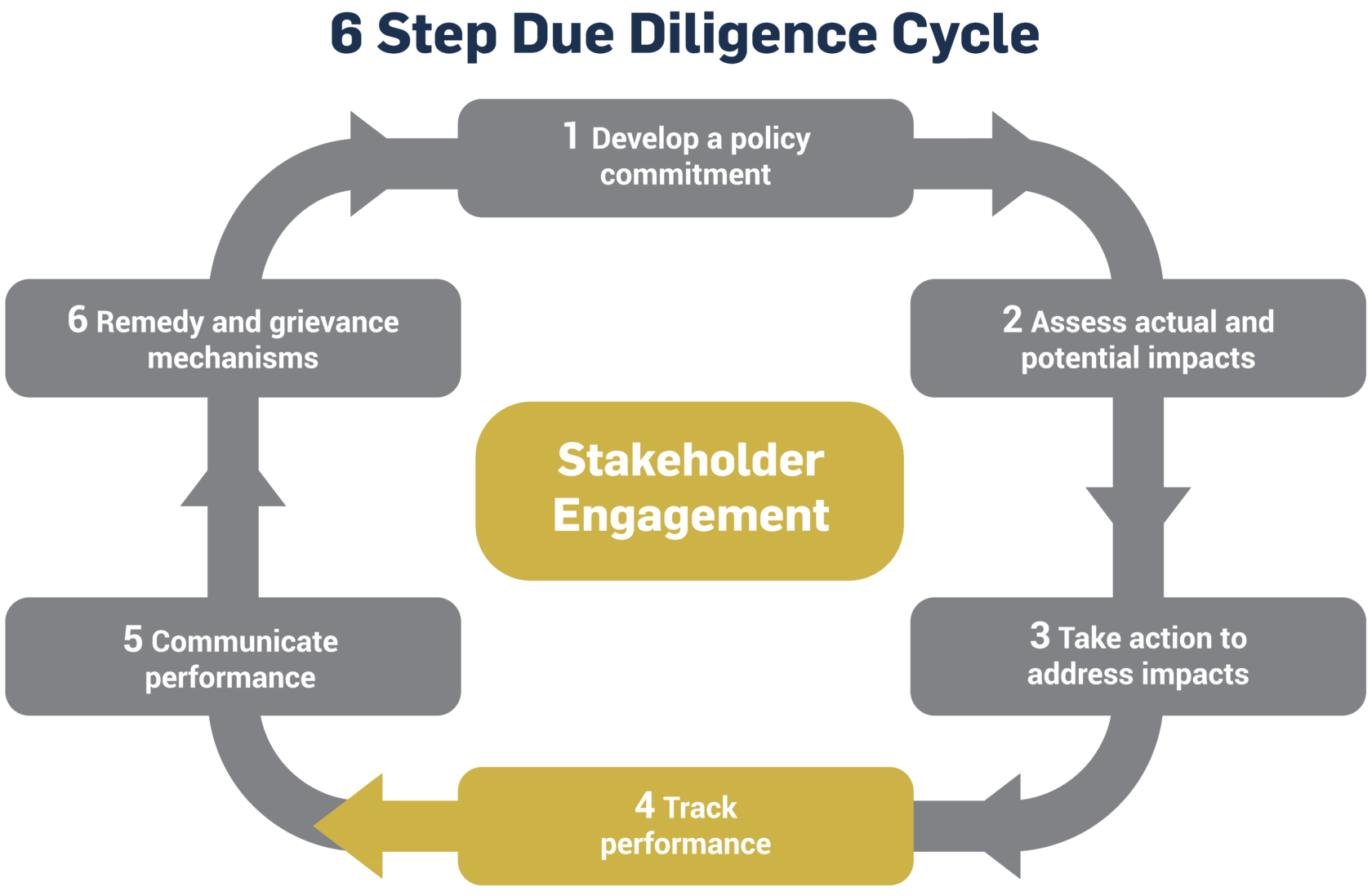

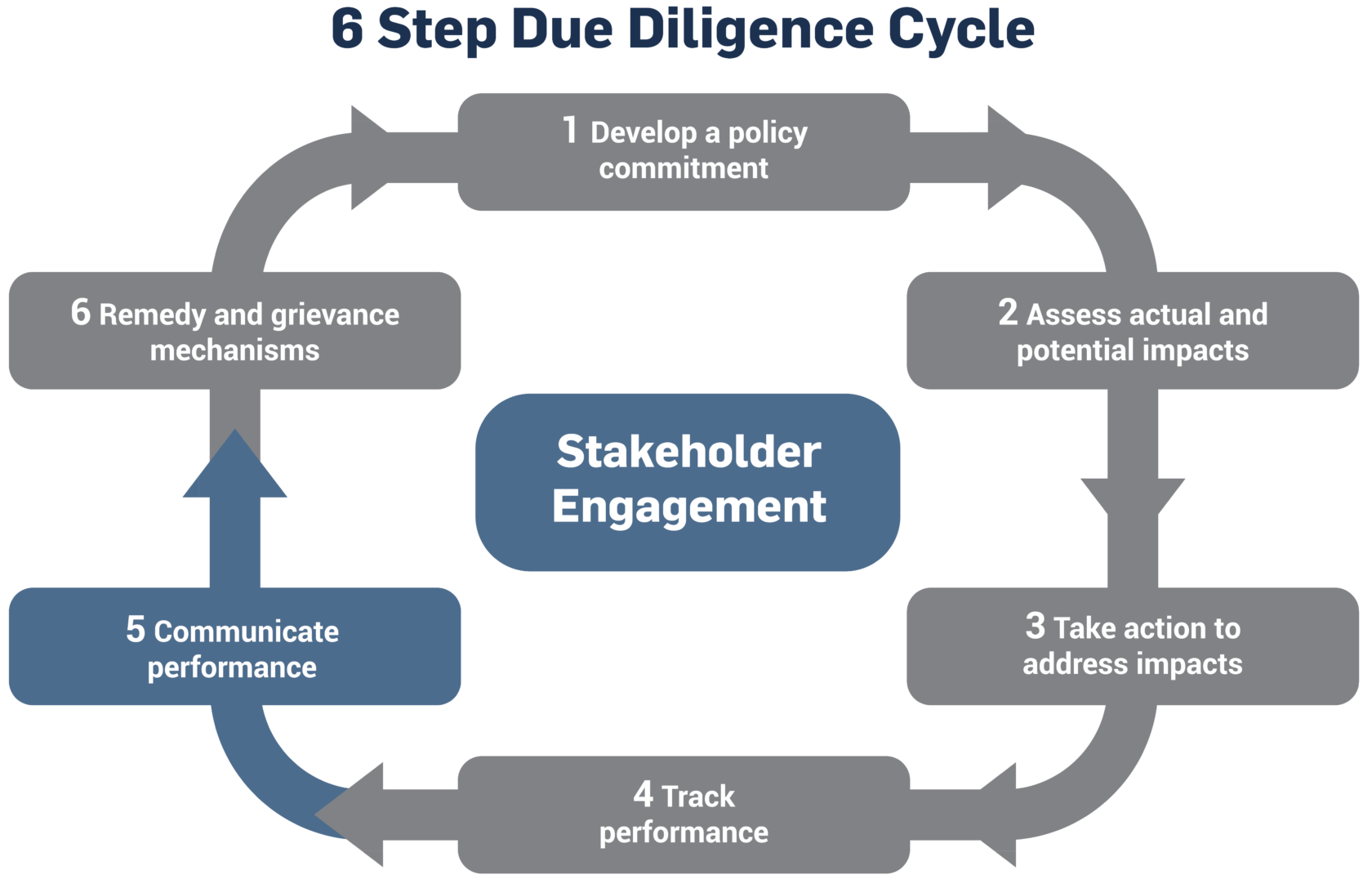

The UNGPs set out how companies, in meeting their responsibility to respect human rights, should put in place due diligence and other related policies and process, which include:

- A publicly available policy setting out the company’s commitment to respect human rights;

- Assessment of any actual or potential adverse human rights impacts with which the company may be involved across its entire value chain;

- Integration of the findings from their impact assessments into relevant internal functions/processes — and the taking of effective action to manage the same;

- Tracking of the effectiveness of the company’s management actions;

- Reporting on how the company is addressing its actual or potential adverse impacts; and

- Remediation of adverse impacts that the company has caused or contributed to.

The steps outlined below follow the UNGPs framework and can be considered a process which a business looking to start implementing human rights due diligence processes can follow.

Additionally, the OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises define the elements of responsible business conduct, including human and labour rights.

Another important reference document is the ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy (MNE Declaration), which contains the most detailed guidance on due diligence as it pertains to labour rights. These instruments, articulating principles of responsible business conduct, draw on international standards enjoying widespread consensus.

Companies can seek specific guidance on this and other issues relating to international labour standards from the ILO Helpdesk for Business. The ILO Helpdesk assists company managers and workers who want to align their policies and practices with principles of international labour standards and build good industrial relations. It has a specific section on forced labour.

Additionally, the SME Compass offers guidance on the overall human rights due diligence process by taking businesses through five key due diligence phases. The SME Compass has been developed in particular to address the needs of SMEs but is freely available and can be used by other companies as well. The tool, available in English and German, is a joint project by the German Government’s Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

1. Develop a Policy Commitment on Forced Labour

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, a human rights policy should be:

- “Approved at the most senior level” of the company;

- “Informed by relevant internal and/or external expertise”;

- Specific about company’s “human rights expectations of personnel, business partners and other parties directly linked to its operations, products or services”;

- “Publicly available and communicated internally and externally to all personnel, business partners and other relevant parties”; and

- “Reflected in operational policies and procedures necessary to embed it throughout the business”.

Benchmarking initiatives such as KnowTheChain show that many companies have over the years made progress in relation to their standards and procedures on forced labour. However, their 2022 findings also show that the average score for ‘Commitment and Governance’, the theme that looks specifically at a company’s commitment to addressing forced labour, across companies of all sectors, is 45 out of 100 (a decrease from the previous report).

Although some companies publish stand-alone forced labour policies — for example, Wilmar International, Aldi South Group and Hewlett Packard — it is more common for businesses to integrate forced labour into their human rights policies with M&S, Unilever and BHP offering some examples. Where companies do not have a stand-alone human rights policy, forced labour is often addressed in other documentation, such as a business code of conduct or ethics and/or a supplier code of conduct. Colgate, Carrefour and Danone are examples of companies that integrate forced labour requirements into their supplier codes of conduct.

The ILO Combating Forced Labour Handbook for Employers and Business includes additional, detailed recommendations on forced labour policy content and applicability. Businesses may also want to check the ILO Helpdesk for Business, which provides answers to the most common questions that businesses may encounter while developing their forced labour policies — or integrating forced labour commitments into other policy documents. Examples include:

- What companies can do to prevent forced labour?

- Is it OK for a company to withhold the passports of migrant workers working in their factory?

- Is it considered forced labour when workers receive only accommodation and food?

- Does compulsory overtime constitute forced labour?

Businesses may also consider aligning their policies with relevant industry-wide or cross-industry policy commitments, for example:

- Responsible Business Alliance (RBA) Code of Conduct

- Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI) Base Code

- amfori BSCI Code of Conduct

- Fair Labor Association (FLA) Code of Conduct

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Combating Forced Labour: A Handbook for Employers and Business: This guidance provides materials and tools for employers and business to strengthen their capacity to address the risk of forced labour and human trafficking in their own operations and in global supply chains, including advice on crafting company policy on forced labour.

- GIFT, Human Trafficking and Business: Good Practices to Prevent and Combat Human Trafficking: A resource developed by the UN Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking and other stakeholders that explains what companies can do to take action against human trafficking. The guide provides advice on what to look out for when developing a policy on human trafficking, including integrating the policy into contracts with suppliers and business partners.

- Sedex and Verité, Supplier Workbook: Chapter 1.2 “Employment is Freely Chosen” includes suggestions on what companies should include in their policies on forced labour.

- United Nations Global Compact-OHCHR, A Guide for Business: How to Develop a Human Rights Policy: This guidance provides recommendations on how to develop a human rights policy and includes extracts from companies’ policies referencing forced labour.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to develop a human rights strategy and formulate a policy statement.

- SME Compass, Policy statement: Companies can use this practical guide to learn to develop a policy statement step-by-step. Several use cases illustrate how to implement the requirements.

- UN Global Compact Labour Principles, Advancing decent work in business Learning Plan: This learning plan, developed by the UN Global Compact and the International Labour Organization, helps companies understand each Labour Principle and its related concepts and best practices as well as practical steps to help companies understand and take action across a variety of issues, including the elimination of all forms of forced and compulsory labour.

2. Assess Actual and Potential Forced Labour Impacts

UNGP Requirements

The UNGPs note that impact assessments:

- Will vary in complexity depending on “the size of the business enterprise, the risk of severe human rights impacts, and the nature and context of its operations”;

- Should cover impacts that the company may “cause or contribute to through its own activities, or which may be directly linked to its operations, products or services by its business relationships”;

- Should involve “meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups and other relevant stakeholders” in addition to other sources of information such as audits; and

- Should be ongoing.

Impact assessments should look at both actual and potential impacts, i.e. impacts that have already manifested or could manifest. This compares to risk assessment that would only look at potential impacts and may not satisfy all of the above criteria.

The ILO Combating Forced Labour Handbook for Employers and Business includes suggestions on how to identify and assess actual and potential forced labour impacts. In particular, forced labour impact assessments should consider the following:

- Forced labour takes many forms, particularly when dealing with vulnerable groups such as migrant workers or student apprentices.

- Assessments should consider conducting off-site interviews as workers may not be comfortable talking about forced labour indicators on-site.

- There is also an increasing trend of assessing risks of forced labour and other labour rights violations through “worker voice” tools, such as technology-enabled worker surveys.

Forced labour impact assessments are most often integrated into broader human rights impact assessments (for example Unilever, Freeport-McMoRan and Ajinomoto). The assessment of forced labour risks can also be incorporated into other internal risk assessments focused on evaluating potential impacts of company operations — see, for example, Danone, Glencore and Kellogg’s.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Combating Forced Labour: A Handbook for Employers and Business: This guidance includes a checklist for enterprise-level impact assessments, including technical advice on how to conduct assessments.

- Global Compact Network Germany, Moderne Sklaverei und Arbeitsausbeutung: A German-language guidance note addressing modern slavery and labour exploitation.

- Global Business Coalition Against Human Trafficking (GBCAT), Resources for Suppliers: A toolkit aimed at helping companies that work in corporate supply chains quickly identify areas of their business that carry the highest risk of modern slavery and develop a simple plan to prevent and address any identified risks.

- IFC, CDC Group, EBRD, DFID, Ergon Associates and Ethical Trading Initiative, Managing Risks Associated with Modern Slavery: A Good Practice Note for the Private Sector: This resource provides detailed guidance on how companies can assess the risk of modern slavery in global supply chains. It provides considerations on workplace assessments, including what to look for on-site.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Base Code Guidance: Modern Slavery: A detailed guide for businesses on assessing the actual and potential risk of forced labour in global supply chains.

- PRI, A Guide for Investor Engagement on Labour Practices in Agricultural Supply Chains: This guidance outlines a six-principle framework to assess potential and actual forced labour impacts in agricultural supply chains.

- Danish Centre Against Human Trafficking, Managing the Risk of Hidden Forced Labour: A Guide for Companies and Employers: This resource provides a do-it-yourself quick risk assessment and checklists in assessing forced labour risks in corporate supply chains.

- US Department of Labor, List of Goods Produced by Child Labour or Forced Labor: This list details forced labour risks in various goods and commodities, which can be used as qualitative data in risk and impact assessments.

- Walk Free, Global Slavery Index: Quantitative datasets covering prevalence, vulnerability and Government response to modern slavery.

- CSR Risk Check: A tool allowing companies to check which international CSR risks (including related to forced labour) businesses are exposed to and what can be done to manage them. The tool provides tailor-made information on the local human rights situation as well as environmental, social and governance issues. It allows users to filter by product/raw material and country of origin. The tool was developed by MVO Netherland; the German version is funded and implemented by the German Government’s Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights and UPJ.

- SME Compass, Risk Analysis Tool: This tool helps companies to locate, asses and prioritize significant human rights and environmental risks long their value chains.

- SME Compass, Supplier review: This practical guide helps companies to find an approach to manage and review their suppliers with respect to human rights impacts.

3. Integrate and Take Action to Address Forced Labour Impacts

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, effective integration requires that:

- “Responsibility for addressing [human rights] impacts is assigned to the appropriate level and function within the business enterprise” (e.g. senior leadership, executive and board level); and

- “Internal decision-making, budget allocations and oversight processes enable effective responses to such impacts”.

The ILO Combating Forced Labour Handbook for Employers and Business includes detailed measures on how companies can prevent or mitigate forced labour in their operations and supply chains.

The actions and systems that a company will need to apply will vary depending on the outcomes of its risk and impact assessments. Examples of such actions include training of company employees and suppliers and multi-stakeholder initiatives:

- Training of company employees and suppliers may cover forced labour laws, company policies and procedures to uncover hidden aspects of forced labour or modern slavery. Training can be delivered in a range of formats, such as online videos, e-learns, in-person sessions or supplier round tables. Coca-Cola, for example, conducts training on human rights (including forced labour) for employees, bottlers, suppliers and auditors. Another example is PepsiCo which conducts training for suppliers on PepsiCo’s Supplier Code of Conduct, which includes the prohibition of forced labour.

- Multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) can provide the necessary expertise, guidance and economies of scale to address forced labour in a responsible, sector-specific way. Such MSIs can also help companies learn from different stakeholder groups including business, Government, civil society and inter-governmental and non-governmental organizations. Aldi South and Inditex are examples of companies that are taking action on forced labour in cotton supply chains through their membership in the Better Cotton Initiative (BCI). Brother Industries Ltd and Microsoft work on the protection of workers vulnerable to forced labour through their membership of the Responsible Business Alliance. The ILO Global Business Network on Forced Labour is another MSI that advances the business case for an end to forced labour. The network is aligned with Alliance 8.7 in aiming to achieve the SDG Target 8.7 of eradicating all forced labour by 2030.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Combating Forced Labour: A Handbook for Employers and Business: This guidance has suggestions of how companies can prevent or mitigate forced labour in their operations and supply chains.

- ILO, Global Guidelines on the Prevention of Forced Labour Through Lifelong Learning and Skills Development Approaches: This guidance on developing forced labour training modules for employees and suppliers, including awareness-raising strategies to identify forced labour risks.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Base Code Guidance: Modern Slavery: A detailed guide on actions that businesses can take to address forced labour in global supply chains.

- Sedex and Verité, Supplier Workbook: Chapter 1.2 “Employment is Freely Chosen” includes suggestions on how companies can address forced labour in their supply chains.

- The Consumer Goods Forum (CGF), Guidance on the Priority Industry Principles for the Implementation of the CGF Social Resolution on Forced Labour: These guidance notes provide advice on the practical action steps companies may take to implement the Priority Industry Principles designed to combat forced labour.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to take action on human rights by embedding them in your company, creating and implementing an action plan, and conducting a supplier review and capacity building.

- SME Compass, Identifying stakeholders and cooperation partners: This practical guide is intended to help companies identify and classify relevant stakeholders and cooperation partners

- SME Compass, Standards Compass: This online tool offers guidance on what to pay attention to when selecting sustainability standards or when participating in multi-stakeholder initiatives. It allows comparing standards and initiatives with respect to their contribution to human rights due diligence and their potential limitations.

4. Track Performance on Forced Labour

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, tracking should:

- “Be based on appropriate qualitative and quantitative indicators”; and

- “Draw on feedback from both internal and external sources, including affected stakeholders” (e.g. through grievance mechanisms).

Businesses should regularly review their approach to forced labour to see if it continues to be effective and is having the desired impact.

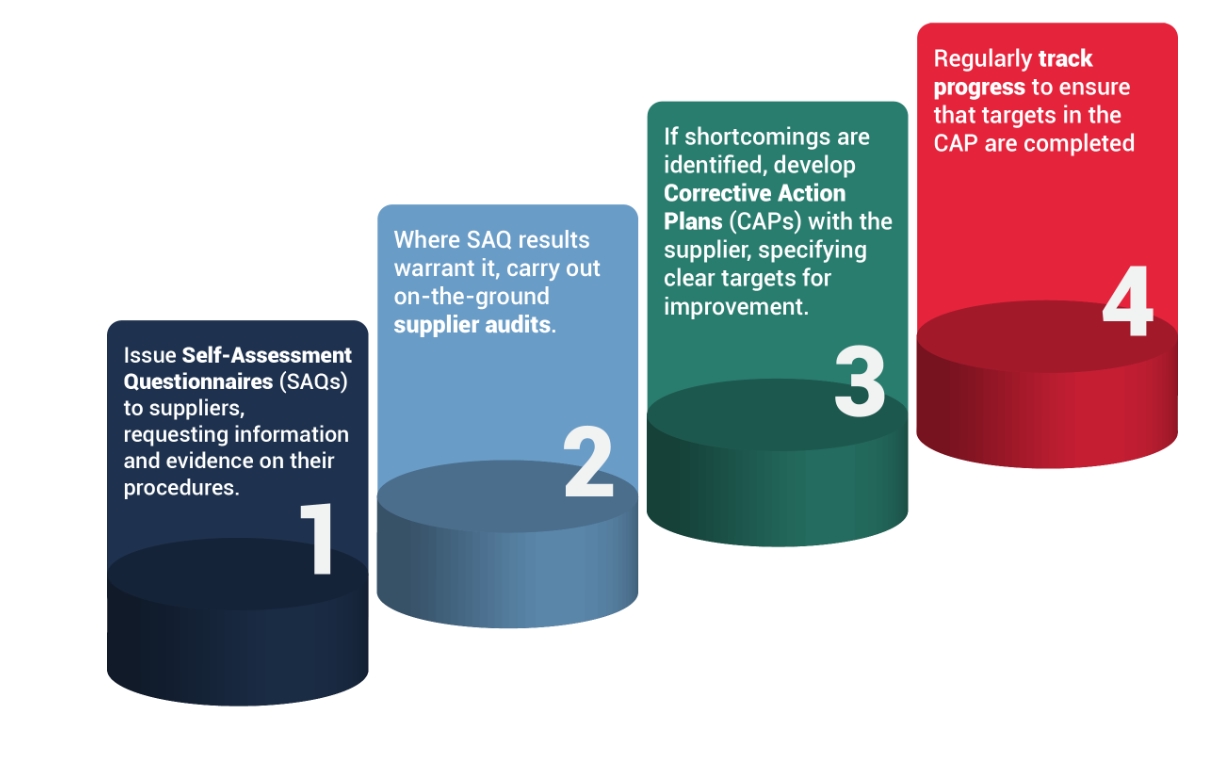

Audits and social monitoring are common ways to check performance in the first tier of the supply chain. Such monitoring or audits can be undertaken internally by the company or a third party contracted by the company. A common approach or first step taken by companies is to issue self-assessment questionnaires (SAQs) to suppliers, requesting information and evidence on their forced labour procedures, such as whether suppliers have implemented monitoring measures to identify groups vulnerable to forced labour. Repeated SAQs can give insight into improvements in supplier management systems and let suppliers self-report on actual or potential forced labour impacts.

Where SAQ results warrant it, companies can carry out on-the-ground (or in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic) remote suppliers audits. Common supplier audit frameworks that span most industries and include forced labour indicators include SMETA audits and SA8000 accredited audits. General Mills, for example, conducts SMETA audits of its suppliers and co-packers.

The ILO Combating Forced Labour Handbook for Employers and Business provides advice on steps to consider in conducting social audits on forced labour (see Booklet 5). In addition, Booklet 4 ‘A Checklist & Guidance for Assessing Compliance’ presents a series of questions to help compliance personnel perform better forced labour assessments. Examples of questions to include in social audits or SAQs include:

- Do workers have the freedom to terminate employment (by means of notice of reasonable length) at any time without a penalty?

- Are non-cash or “in-kind” payments used as a means to create a state of dependency of the worker on the employer?

- Is there any evidence that disciplinary sanctions require or result in an obligation to work, for example through punishment for having participated in a strike?

- Are workers forced to work more overtime hours than allowed by national law or (where relevant) collective agreement, under the menace of a penalty?

- Is there evidence that employers who engage private employment agencies have taken measures to monitor such agencies and prevent abuses related to forced labour and human trafficking?

If shortcomings are identified, corrective action plans should be developed jointly with the supplier, setting out clear targets and milestones for improvement. Progress should then be tracked regularly to completion.

Setting SMART targets on forced labour helps objectively track performance. SMART targets are those that are: specific, measurable, attainable, resourced and time-bound. Examples of indicators to be recorded and monitored include:

- Forced labour grievances recorded (number and nature)

- Audit findings on forced labour

- Progress on Corrective Action Plans

- Media reports on instances of forced labour

- Official inspection outcomes

Responsibility for data collection should be clearly allocated to relevant roles within the company and reported with a set frequency (for instance once a month).

Although both SAQs and audits are commonly used by companies in various industries, both tools have limitations in their ability to uncover hidden violations, including forced labour. Unannounced audits somewhat mitigate this problem but even these are not always effective at identifying violations given that an auditor tends to spend only limited time on-site. Furthermore, human rights violations, including forced labour, often happen further down supply chains, whereas audits often only cover ‘Tier 1’ suppliers.

New tools such as technology-enabled worker surveys/‘worker voice’ tools allow real-time monitoring and partly remedy the problems of traditional audits. An increasing number of companies complement traditional audits with ‘worker voice’ surveys (e.g. Unilever and VF Corporation), which can be easily adapted to different languages to accommodate workers’ needs.

Some companies go further and adopt ‘beyond audit’ approaches, which are built on proactive collaboration with suppliers rather than on supplier monitoring (‘carrots’ rather than ‘sticks’). Collaborating with other stakeholders, including workers’ organizations, law enforcement authorities, labour inspectorates and non-governmental organizations to proactively identify, remediate and prevent forced labour can also prove to be effective in tracking performance on forced labour. Partnering with other stakeholders to design an effective monitoring mechanism will allow companies to better track progress.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Combating Forced Labour: A Handbook for Employers and Business: This guidance has suggestions on how companies can track performance on forced labour in their operations and supply chains.

- IFC, CDC Group, EBRD, DFID, Ergon Associates and Ethical Trading Initiative, Managing Risks Associated with Modern Slavery — A Good Practice Note for the Private Sector: This resource provides the private sector with guidance on how to monitor progress on forced labour.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Base Code Guidance: Modern Slavery: A detailed guide for businesses on eliminating forced labour in global supply chains.

- Sedex and Verité, Supplier Workbook: Chapter 1.2 “Employment is Freely Chosen” includes suggestions on how companies can monitor forced labour in their supply chains.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to measure human rights performance.

- SME Compass, Key performance indicators for due diligence: Companies can use this overview of selected quantitative key performance indicators to measure implementation, manage it internally and/or report it externally.

5. Communicate Performance on Forced Labour

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, regular communications of performance should:

- “Be of a form and frequency that reflect an enterprise’s human rights impacts and that are accessible to its intended audiences”;

- “Provide information that is sufficient to evaluate the adequacy of an enterprise’s response to the particular human rights impact involved”; and

- “Not pose risks to affected stakeholders, personnel or to legitimate requirements of commercial confidentiality”.

As forced labour is a severe human rights violation, companies are expected to communicate their performance on forced labour in a formal public report, which can take the form of a standalone report such as Nestlé’s Responsible Sourcing of Seafood reports. More commonly, however, an update on progress with addressing forced labour risks is included in a broader sustainability or human rights report such as Unilever’s Human Rights reports, or in an annual Communication on Progress (CoP) in implementing the Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact. Additionally, other forms of communication may include in-person meetings, online dialogues and consultation with affected stakeholders.

Mandatory reporting now requires companies in certain jurisdictions to publish annual statements on modern slavery or identify forced labour risks in their supply chains. Hewlett Packard, Intel and Cisco Systems Inc. are among the top performers of KnowTheChain 2022 Benchmark and have communicated their performance on forced labour through their mandatory reporting requirements.

The ILO Combating Forced Labour Handbook for Employers and Business provides recommendations on how companies may want to communicate their activities to wider stakeholders, including through the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) or the UN Global Compact.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Combating Forced Labour: A Handbook for Employers and Business: This guidance has helpful recommendations on how to report forced labour approaches and results.

- Global Reporting Initiative, GRI409: Forced or Compulsory Labor 2016: GRI sets out the reporting requirements on forced labour for companies to achieve standard 409.

- GRI-Responsible Labour Initiative (RLI), Advancing Modern Slavery Reporting to Meet Stakeholder Expectations: This toolkit provides guidance for companies on due diligence reporting and measures related to modern slavery across the value chain.

- The Social Responsibility Alliance (SRA), The Slavery & Trafficking Risk Template (STRT): Free, open-source industry standard template used to assist companies in their efforts to comply with human trafficking and modern slavery legislation and improve their supply chain-related public disclosures.

- Social Accountability International, Measure & Improve Your Labor Standards Performance: This resource includes tools to help companies implement or improve performance on labour standards, including preventing forced labour in global supply chains.

- UNGP Reporting Framework: A short series of smart questions (‘Reporting Framework’), implementation guidance for reporting companies, and assurance guidance for internal auditors and external assurance providers.

- United Nations Global Compact, Communication on Progress (CoP): The CoP ensures further strengthening of corporate transparency and accountability, allowing companies to better track progress, inspire leadership, foster goal-setting and provide learning opportunities across the Ten Principles and SDGs.

- The Sustainability Code: A framework for reporting on non-financial performance that includes 20 criteria, including on human rights and employee rights.

- SME Compass, Target group-oriented communication: This practical guide helps companies to identify their stakeholders and find suitable communication formats and channels.

6. Remedy and Grievance Mechanisms

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, remedy and grievance mechanisms should include the following considerations:

- “Where business enterprises identify that they have caused or contributed to adverse impacts, they should provide for or cooperate in their remediation through legitimate processes”.

- “Operational-level grievance mechanisms for those potentially impacted by the business enterprise’s activities can be one effective means of enabling remediation when they meet certain core criteria.”