Created in partnership with the Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights

Child Labour

Nearly 1 in 10 children worldwide are subjected to child labour, a number that has risen for the first time in two decades and is likely to increase further due to global climate, health and security crises.Overview

What is Child Labour?

Child labour is work that harms children’s well-being and hinders their education, development and future livelihood, according to the International Labour Organization (ILO). Not all child labour is harmful; for example, if it is light work and does not interfere with a child’s education or right to leisure, such as, children helping their parents on a farm with non-harmful activities or in a shop outside of school hours. Moreover, youth employment and student work are considered legal and may contribute positively to the development of children and young people.

What is the Dilemma?

The dilemma for responsible business is how to address child labour responsibly given the complex social and economic context in which it occurs. While a business may seek to respect the principles contained in international labour standards and national laws on minimum age, removing children (or having children removed) from their operations or supply chains without considering the implications for them could potentially worsen their situation. For example, removing children from the workplace without providing safer and suitable alternatives may leave them vulnerable to more exploitative work elsewhere (e.g. in subcontractor companies), as well as potentially lead to negative health and well-being implications due to increased poverty within their family.

Prevalence of Child Labour

The ILO and UNICEF estimate that 160 million children — 63 million girls and 97 million boys — were in child labour globally at the beginning of 2020, accounting for almost 1 in 10 of all children worldwide.[2] 79 million children (nearly 50% of all children in child labour) were involved in hazardous work such as agriculture or mining, operating dangerous machinery or working at height. However, this number is an approximation — child labour is difficult to quantify as it is often hidden due to its illegal nature. The identification of children in the workplace can be further impeded by a lack of reliable documents such as birth certificates and the fact that it often occurs in rural settings or in areas of cities where authorities have little visibility.

Key trends include:

- Global progress against child labour has stagnated since 2016 despite global efforts to eradicate child labour by 2025, as per target 8.7[1] of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

- The COVID-19 crisis threatened to further erode global progress against child labour. ILO estimates suggested that a further 8.9 million children would be in child labour by the end of 2022 due to rising poverty and parental deaths driven by the pandemic.

- Since the start of the pandemic, child labour risks increased in more than 83 countries. Africa remains the highest risk region, with 6 of the 10 highest risk countries (Verisk Maplecroft). According to an ILO report published in June 2021, there are more children in child labour in sub-Saharan Africa than in the rest of the world combined.

- The year 2021 was designated as the International Year for the Elimination of Child Labour by UN Member States to further increase global efforts in eliminating child labour.

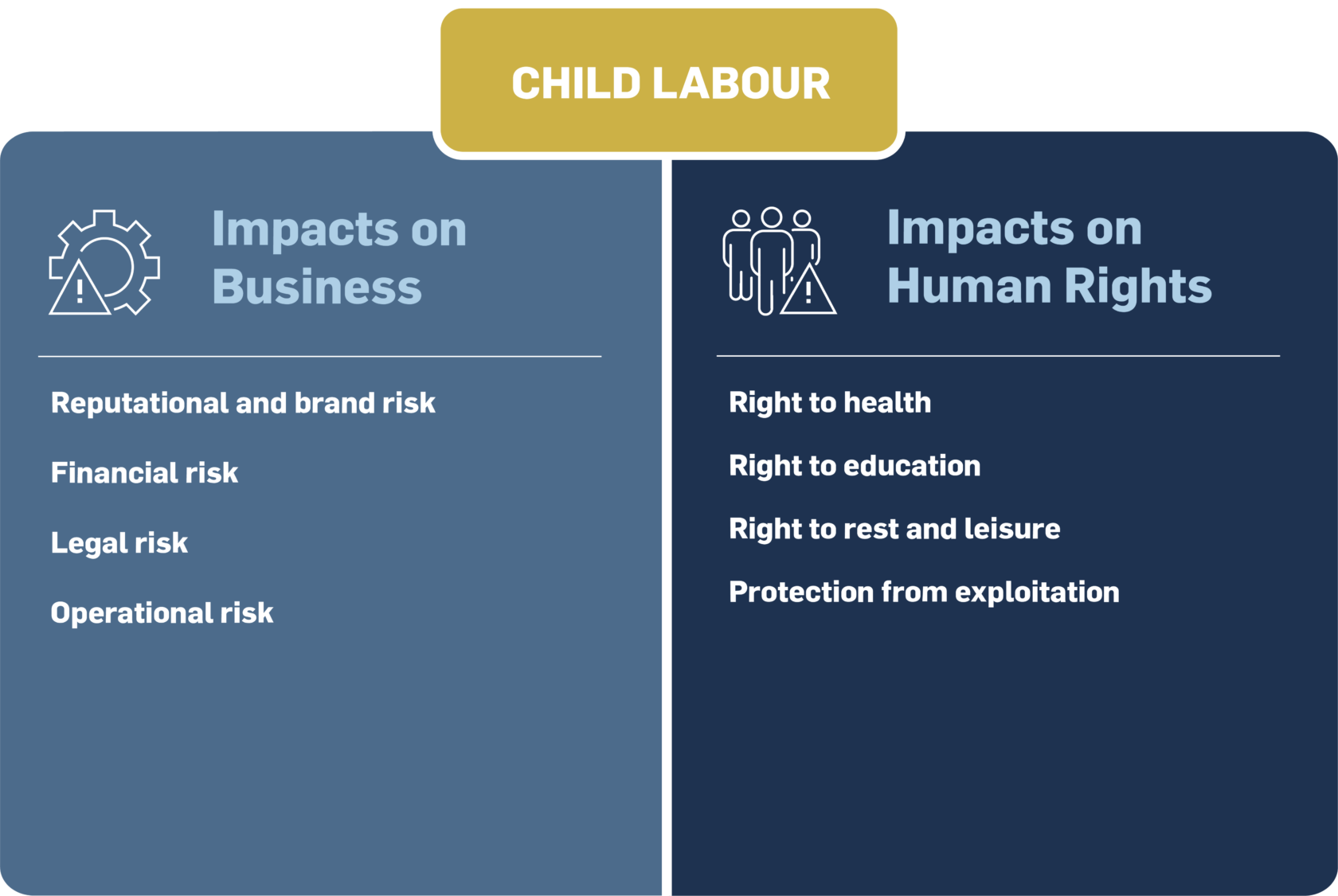

Impacts on Businesses

Businesses can be impacted by child labour risks in their operations and supply chains in multiple ways:

- Reputational and brand risk: Campaigns by NGOs, trade unions, consumers, media and other stakeholders can result in reduced sales and/or brand erosion.

- Financial risk: Divestment and/or avoidance by investors and finance providers (many of which are increasingly applying environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria to their decision-making) can result in reduced or more expensive access to capital and reduced shareholder value.

- Legal risk: Legal charges can be brought against the company, up to and including criminal charges, which can result in imprisonment in some countries and usually involve significant fines and/or surrendering of goods produced by child labour (see section ‘Definition and Legal Instruments’). Former child workers may also be able to sue their exploitative employers, potentially including companies further up in the supply chain.

- Operational risk: Changes to a company’s supply chains made in response to the discovery of child labour may result in disruption. For example, companies may feel the need to terminate supplier contracts (resulting in potentially higher costs and/or disruption) and direct sourcing activities to lower-risk locations.

Impacts on Children’s Rights

Child labour has the potential to impact a range of children’s rights,[3] including but not limited to:

- Right to health and to an adequate standard of living (CRC, Articles 6.2 and 27.1): Children’s health and personal development may be negatively impacted through engagement in work activities, which are not age-appropriate.

- Right to education (CRC, Article 28): Working hours may preclude children from attending school. Likewise, working children may be too tired to benefit fully from their studies. Children’s ability to learn and join the formal labour market at a later date may also be compromised by child labour.

- Right to rest and leisure and to cultural life (CRC, Article 31.1): Children involved in child labour often do not have sufficient time to develop socially and culturally through play and interaction with other children.

- Right to protection from economic exploitation (CRC, Article 32): Children have the right to be protected from economic exploitation. This includes the right to be protected from work that is hazardous or likely to interfere with the child’s health or physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development.

For further information on children’s rights, please refer to UNICEF’s helpful summary of children’s rights listed in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The following SDG targets relate to child labour:

- Goal 8 (“Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all”), Target 8.7: Take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labour, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms

- Goal 16 (“Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels”), Target 16.2: End abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence and torture against children

Progress on these targets and Global Goals will also help advance other goals, for example Goal 3 (“Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages”) and Goal 4 (“Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”).

Key Resources

Key Resources

The following resources provide further information on how businesses can address child labour responsibly in their operations and supply chains:

- ILO and UNICEF, Child Labour: Global Estimates 2020, Trends and the Road Forward: The most up-to-date global estimates of child labour from the ILO and UNICEF, including an overview of the impact on child labour from COVID-19.

- ILO and International Organisation of Employers (IOE), Child Labour Guidance Tool for Business: This tool helps companies meet the due diligence requirements laid out in the UN Guiding Principles, as they pertain to child labour.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Base Code Guidance: Child Labour: A step-by-step guide for businesses on eliminating child labour in global supply chains.

Definition & Legal Instruments

Definition

According to the ILO, the term “child labour” is work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development. It refers to work that:

- Is mentally, physically, socially, or morally dangerous and harmful to children; and/or

- Interferes with their schooling by depriving them of the opportunity to attend school; obliging them to leave school prematurely; or requiring them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work.

It is important to distinguish between minimum age violations and the worst forms of child labour. The minimum age for work is defined as follows:

- The minimum age for work should not be less than the age for completing compulsory schooling, and in general, not less than 15 years. However, States whose economy and educational facilities are insufficiently developed may initially specify a minimum age of 14 years as a transitional measure (Minimum Age Convention No. 138).

- Children can engage in light work from 13 years of age (or 12 as a transitional measure), provided that it does not interfere with their education or vocational training and that it does not have a negative impact on their health (Minimum Age Convention No. 138).

The worst forms of child labour include (Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention No. 182):

- The sale and trafficking of children, debt bondage and serfdom and forced or compulsory labour, including forced or compulsory recruitment of children for use in armed conflict;

- The use, procuring or offering of a child for prostitution or pornographic performances;

- The use, procuring or offering of a child for illicit activities (e.g. production and trafficking of drugs).

Child labour also includes hazardous work performed by young workers over the legal minimum age for work but under 18 years. According to the ILO, hazardous work is defined as work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children.

Examples of hazardous child labour include:

- Work that exposes children to physical, psychological or sexual abuse;

- Work underground, underwater, at dangerous heights or in confined spaces;

- Work with dangerous machinery, equipment and tools, or which involves the manual handling or transport of heavy loads;

- Work in an unhealthy environment which may, for example, expose children to hazardous substances, agents or processes, or to temperatures, noise levels, or vibrations damaging to their health;

- Work under particularly difficult conditions such as work for long hours or during the night or work where the child is unreasonably confined to the premises of the employer.

The ILO provides further guidance on types of hazardous work, while national legislation often includes lists of prohibited hazardous activities for children. It is important to note that the list of prohibited hazardous activities will vary between states, depending on a variety of contextual factors; it is, therefore, often better to follow best practice and work to prevent children working in hazardous jobs.

Legal Instruments

ILO and UN Conventions

Two ILO Conventions and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child provide the framework for national law to define a clear line between what is acceptable and what is not in terms of child employment. The effective abolition of child labour is one of the five fundamental rights and principles at work by the ILO which Member States must promote, irrespective of whether or not they have ratified the respective conventions listed below

- ILO Minimum Age Convention, No. 138 (1973) sets a general minimum age of 15 for employment with some exceptions for developing countries.

- ILO Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, No. 182 (1999) prohibits worst forms of child labour, including hazardous work by young workers under 18.

- The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child prohibits child labour and requires signatories to regulate minimum age and conditions of work for children.

The ILO Convention No. 182 has been ratified by all 187 ILO Member States (the only ILO Convention that has achieved universal ratification). The UN Convention on the Right of the Child has also been ratified by all countries except the United States (although the United States signed the Convention). Furthermore, most States have ratified ILO Convention No. 138. This means that in most countries relevant national legislation should be in place to implement the terms of these international legal instruments. In due diligence, it is important to check the ratification status for particular countries as an indicator of potentially more limited state protections against child labour. However, ratification does not guarantee that these countries are free from child labour, as the existence and enforcement of national laws to address child labour varies.

The fight against child labour is included as one of the Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact: “Principle 5: Businesses should uphold the effective abolition of child labour”. The four labour principles of the UN Global Compact are derived from the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work.

These fundamental principles and rights at work have been affirmed and developed in the form of specific rights and obligations in International Labour Conventions and Recommendations and cover issues related to child labour, discrimination at work, forced labour and freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining.

Member States of the ILO have an obligation to promote the effective abolition of child labour, even if they have not ratified the Conventions in question.

Other Legal Instruments

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) set the global standard regarding the responsibility of businesses to respect human rights in their operations and across their value chains. The Guiding Principles call upon States to consider a smart mix of measures — national and international, mandatory and voluntary — to foster business respect for human rights. Businesses should consider the UNGPs in their operational and supply chain decisions, and when following national legislation.

Children’s Rights and Business Principles (CRBPs) were first proposed in 2010 and are based on existing standards, initiatives and best practices related to business and children. These Principles seek to define the scope of corporate responsibility towards children. Covering a wide range of critical issues – from child labour to marketing and advertising practices to the role of business in aiding children affected by emergencies – the Principles call on companies everywhere to respect children’s rights through their core business actions, but also through policy commitments, due diligence and remediation measures.

Regional and Domestic Legislation

Companies are increasingly subject to non-financial reporting requirements and due diligence obligations in the jurisdictions in which they operate, which often include disclosures on their performance. There are several high-profile examples of national legislation that specifically mandate human rights-related reporting and other positive legal duties, such as due diligence, including the United Kingdom Modern Slavery Act 2015, Australian Modern Slavery Act 2018, the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act 2010, the French Corporate Duty of Vigilance Law 2017, the German Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains 2023 and the Norwegian Transparency Act 2022.

Also, in 2021 the Netherlands submitted a Bill for Responsible and Sustainable International Business Conduct, and the European Commission announced its Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). This Directive is likely to come into force between 2025 and 2027 and will make human rights and environmental due diligence mandatory for larger companies.

These mandatory due diligence and disclosure laws require companies to publicly communicate their efforts to address actual and potential human rights impacts, including the worst forms of child labour. Failure to comply with these obligations leads to real legal risk for companies.

Contextual Risk Factors

The prevention of child labour requires an understanding of its underlying causes and the consideration of a wide range of issues which may increase the risk of child labour, that often interfere and reinforce one another, such as inadequate family income and poor or non-existent educational facilities.

Key risk factors include:

- High rates of poverty and unemployment, especially where there is a lack of state support (e.g. unemployment benefits). In regions where adult unemployment is high, children may be required to work to assist the family.

- Low wages can exacerbate the prevalence of poverty and drive the need for children to work alongside their parents to supplement household income (see Living Wage issue).

- Lack of educational opportunities for children due to a lack of school facilities or where school tuition costs and educational materials are considered too expensive. Where educational facilities or other forms of childcare are missing, children tend to accompany (and often help) their parents at work.

- Lack of safe alternative pathways to employment results in adolescents finding themselves moving from one form of hazardous work to another. The alternative is for adolescents to have access to safe work that could lead to long-term employment.

- Poorly enforced domestic labour laws due to a lack of government resources, capacity or commitment to fully implement state duty to protect citizens against human rights violations. This can result in a lack of or inadequate training of labour inspectors, as well as improper payments made by employers to (sometimes poorly compensated) inspectors to overlook child labour violations.

- Informal economies are associated with higher child labour risks. Informality often leads to lower and less regular incomes, inadequate and unsafe working conditions, extreme job precarity and exclusion from social security schemes, among other factors. All of these can spur families to turn to child labour in the face of financial distress.

- Rural areas are also associated with a higher prevalence of child labour. There are 122.7 million rural children (13.9%) in child labour compared to 37.3 million urban children (4.7%). Job opportunities are often scarce in rural areas, leaving children to find work to assist their families, with government oversight of these areas much lower.

- Intersectionality, or the interaction between gender, race, ethnicity, age and other categories of difference, leads to increased child labour risks. For example, girls from an ethnic minority living in poor rural areas may be more exposed to the risks of child labour exploitation.

Industry-specific Risk Factors

Whilst child labour is present in many industries, the following present particularly significant levels of risk. To identify potential child labour risks for other industries, companies can access the CSR Risk Check.

Agriculture

According to ILO 2020 estimates, around 70% of child labourers around the world — 112 million children — work in agriculture, including fishing, aquaculture and livestock rearing. Although certain work on family farms is acceptable for children — provided that it is not hazardous and does not prevent them from receiving an education — many forms of child work in agricultural supply chains are not legal. The US Department of Labor’s 2022 report suggests that the most common items produced by child labour in agriculture include bananas, cattle and dairy products, cocoa, coffee, cotton, fish, rice, sugar and tobacco.

Agriculture-specific risk factors include the following:

- Piece rate: Many agricultural jobs are paid by the amount of produce picked, which encourages parents to bring their children along with them to help collect greater volumes.

- Seasonal migrant labour: The agricultural sector traditionally relies heavily on migrant labour due to seasonality. This can mean the children of migrant labourers are often not in one place long enough to attend school, so work with their parents in the field instead.

- Families: Family-based child labour is hard for companies to identify, as family farms usually feed into larger co-operatives or wholesalers and are relatively invisible within the supply chain. Furthermore, family-based child labour can be easily hidden on inspection.

Helpful Resources

- OECD-FAO, Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains: This guidance provides a common framework to help agro-businesses and investors support sustainable development and identify and prevent child labour.

- FAO, Framework on Ending Child Labour in Agriculture: This framework guides the FAO and its personnel on the integration of measures addressing child labour within FAO’s typical work, programmes and initiatives.

- FAO, Regulating Labour and Safety Standards in the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Sectors: This resource provides information on international labour standards that apply in agriculture, including those on child labour.

- FAO, e-Learning Academy: Business Strategies and Public-Private Partnerships to End Child Labour in Agriculture: This course presents several business-oriented strategies to reduce child labour in agricultural supply chains.

- ILO, Child Labour in the Primary Production of Sugarcane: This report provides an overview of the sugarcane industry, including key challenges and opportunities in addressing child labour.

- Fair Labor Association, ENABLE Training Toolkit on Addressing Child Labor and Forced Labor in Agricultural Supply Chains: This toolkit guides companies on supply chain mapping and the abolition of child labour in supply chains. It contains six training modules, a facilitator’s guide, presentation slides and a participant manual.

- Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), From Farm to Table: Ensuring Fair Labour Practices in Agricultural Supply Chains: This resource provides guidelines on what investors should be looking for from companies to eliminate labour abuses in their agricultural supply chains.

- Sustainable Agriculture Initiative (SAI) Platform: The SAI Platform guidance document on child labour facilitates the development of their members’ policies on child labour.

- Rainforest Alliance, Child Labor Guide: This guide has been developed to support the efforts of farm management to address the risks of child labour on their farms with a focus on coffee, cocoa, hazelnut and tea; however, it can be used for other crops as well.

- German Initiative on Sustainable Cocoa: This multi-stakeholder initiative aims to improve the livelihood of cocoa farmers and their families, as well as to increase the proportion of certified cocoa according to sustainability standards. The Initiative’s background paper provides helpful information on child labor in the West African cocoa sector and possible solutions to address it.

- Fairtrade International, Guide for Smallholder Farmer Organisations – Implementing Human Rights and Environmental Due Diligence (HREDD): This guidance was developed to provide advice and tools on HREDD for farmer organisations to implement.

- UNICEF, Mapping Child Labour Risks in Global Supply Chains: This paper provides a detailed analysis of the Apparel, Electronics and Agricultural Sectors. It was written as a background report for the Alliance 8.7 report on “Ending child labour, forced labour and human trafficking in global supply chains”.

Fashion and Apparel

The fashion and apparel industry may be linked to significant child labour risks. Fashion and apparel-specific risk factors include the following:

- Subcontracting: This industry features a lot of subcontracting and outsourcing, making tracing where a product was made and by whom difficult. In-depth due diligence checks on this part of a supply chain are, therefore, often overlooked.

- Homeworking: Homeworking is particularly hard to monitor, as the location of homeworking is often unknown to companies and there is no way to control working hours or who is doing the work. Research from the University of California, Berkeley, shows that the activities often outsourced to homeworkers are usually finishing tasks, such as beading, embroidery or adding tassels — activities that require delicate handiwork as opposed to being produced by machinery in a factory. Children’s smaller hands can be considered useful for this delicate handiwork.

- Gender: There is a significant gender aspect in this regard, with studies showing most homeworkers in the apparel industry are women and girls (see Gender Equality issue).

Helpful Resources

- OECD, Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains in the Garment & Footwear Sector: The guidanceaims to help fashion and apparel businesses implement the due diligence recommendations contained in the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises in order to avoid and address the potential negative impacts of their activities and supply chains on a range of human rights, including child labour.

- Fair Wear Foundation, The Face of Child Labour: Stories from Asia’s Garment Sector: This reportseeks to promote a greater understanding of the realities of child labour by presenting interviews with children who were found working in Asia’s garment sector.

- Fair Labor Association, Child Labor in Cotton Supply Chains: Collaborative Project on Human Rights in Turkey: The reportexplores cotton and garment supply chains in Turkey and provides recommendations for companies and other stakeholders on eliminating child labour from cotton supply chains.

- Fair Labor Association, Children’s Lives at Stake: Working Together to End Child Labour in Agra Footwear Production: The reportdemonstrates a high prevalence of child labour in shoe production in Agra, India, and provides recommendations for brands, including on enhancing their subcontracting policies.

- SOMO, Branded Childhood: How Garment Brands Contribute to Low Wages, Long Working Hours, School Dropout and Child Labour in Bangladesh: This reportillustrates a link between child labour and low wages for adult workers and provides a series of concrete recommendations for brands and retailers sourcing from Bangladesh on combatting child labour.

- Save the Children, In the Interest of the Child? Child Rights and Homeworkers in Textile and Handicraft Supply Chains in Asia: This studyprovides data on both the positive and negative impact of home-based work and work in small workshops on child rights and identifies best practices to improve child rights in such settings.

- UNPRI, An Investor Briefing on the Apparel Industry: Moving the Needle on Labour Practices: The resourceguides institutional investors on how to identify negative human rights impacts in the apparel industry, including those pertaining to child labour.

- The Partnership for Sustainable Textiles, Bündnisziele: Sozialstandards (German): The Partnership for Sustainable Textiles — a multi-stakeholder initiative with about 135 members from business, Government, civil society, unions, and standards organizations — has formulated social goals, including on child labour, that all members recognize by joining the Partnership.

- Green Button: Certification labelfor sustainable textiles run by the German Government with ban on forced and child labour as one of the certification criteria.

- UNICEF, Mapping Child Labour Risks in Global Supply Chains: This paper provides a detailed analysis of the Apparel, Electronics and Agricultural Sectors. It was written as a background report for the Alliance 8.7 report on “Ending child labour, forced labour and human trafficking in global supply chains”.

Mining and the Extractive Industry

Child labour takes place in parts of the informal artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) industry and has been associated with the mining of “conflict minerals” — tantalum, tin, tungsten and gold — among other minerals such as cobalt. ASM work can be dangerous and personal protective equipment (PPE) is rarely provided. The US Department of Labor’s 2022 report suggests that gold, coal, granite, gravel, diamonds and mica are all associated with child labour.

Mining-specific risk factors include the following:

- Small and slight: Children are often involved in digging as they can get into tighter spaces to mine, or in carrying mined products like gems or metals between extraction sites and refining/washing/filtering sites.

- Global supply chains: Minerals mined by children can end up in global supply chains, including those of automobiles, construction, cosmetics, electronics, and jewellery. For example, the increased production of electric vehicle (EV) batteries has led to the growing demand for cobalt — an essential battery input. Approximately 70% of cobalt (as of January 2023) comes from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), one of the poorest and most unstable countries in the world where ASM activity is common, thus increasing child labour risks.

Helpful Resources

- OECD, Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas: The OECD guidance identifies the worst forms of child labour as a serious human rights abuse associated with the extraction, transport or trade of minerals. The guidance has practical actions for companies to identify and address the worst forms of child labour in mineral supply chains and conduct related due diligence.

- OECD, Practical actions for companies to identify and address the worst forms of child labour in mineral supply chains: This report has been designed for companies to help them identify, mitigate and account for the risks of child labour in their mineral supply chains.

- ILO, Child Labour in Mining and Global Supply Chains: This brief report outlines the scope of child labour in ASM, risks to children’s health and welfare, and recommendations for businesses on addressing this issue.

- ILO, Mapping Interventions Addressing Child Labour and Working Conditions in Artisanal Mineral Supply Chains: This report provides a high-level review of projects and initiatives that aim to address child labour in the ASM sector across different minerals.

- UNICEF, Child Rights and Mining Toolkit: Best Practices for Addressing Children’s Issues in Large-Scale Mining: This toolkit is designed to help industrial miners design and implement social and environmental strategies (from impact assessment to social investment) that respect and advance children’s rights, including the elimination of child labour.

- SOMO, Global Mica Mining and the Impact on Children’s Rights: This report outlines mica production globally and identifies direct or indirect links to child labour.

- SOMO, Beauty and a Beast: Child Labour in India for Sparkling Cars and Cosmetics: This report focuses on illegal mica mining in India. It outlines the due diligence actions of several multinational companies and provides further recommendations for mica mining, processing and/or using companies.

- Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC), Responsible Jewellery Council Standards Guidance: This guidance provides a suggested approach for RJC members to implement the mandatory requirements of the RJC Code of Practice (COP), including the elimination of child labour in mining operations.

- Responsible Minerals Initiative, Material Change: A Study of Risks and Opportunities for Collective Action in the Materials Supply Chains of the Automotive and Electronics Industries: This report examines responsible sourcing of materials in the automotive and electronics industries, including association with child labour. Responsible Minerals Initiative also has other helpful resources for mining companies on various steps of human rights due diligence.

- UNICEF, Mapping Child Labour Risks in Global Supply Chains: This paper provides a detailed analysis of the Apparel, Electronics and Agricultural Sectors. It was written as a background report for the Alliance 8.7 report on “Ending child labour, forced labour and human trafficking in global supply chains”.

- UNICEF, Extractive Pilot – Children’s Rights in the Mining Sector: This report seeks to understand the the impacts of the mining industry on children’s rights and facilitate the integration of children’s rights into companies’ human rights due diligence processes.

Electronics Manufacturing

The electronics manufacturing industry poses child labour risks, as well as risks for young workers.

Industry-specific risk factors include the following:

- Work experience: In several Asian and South-East Asian countries, there are government programmes with major businesses for students and young workers to get work experience. However, there are reports of these programmes being abused, with student and young workers having their IDs faked so they can work longer and more hazardous hours.

- Materials: Electronics companies may be linked to child labour via their mineral supply chains given that some of the minerals and metals used to manufacture electronic components can be associated with significant child labour risks (i.e. during the mining process), such as gold — see the section on mining.

Helpful Resources

- Responsible Business Alliance (RBA),Student Workers Management Toolkit: This toolkit helps human resources and other managers support responsible recruitment and management of student workers in electronics manufacturing.

- Responsible Minerals Initiative, Material Change: A Study of Risks and Opportunities for Collective Action in the Materials Supply Chains of the Automotive and Electronics Industries: This report examines responsible sourcing of materials in the automotive and electronics industries, including association with child labour.

- SOMO, Gold from Children’s Hands: Use of Child-Mined Gold by the Electronics Sector: This report outlines the magnitude and seriousness of child labour in the artisanal gold mining sector and provides insight into the supply chain linkages with the electronics industry.

- UNICEF, Mapping Child Labour Risks in Global Supply Chains: This paper provides a detailed analysis of the Apparel, Electronics and Agricultural Sectors. It was written as a background report for the Alliance 8.7 report on “Ending child labour, forced labour and human trafficking in global supply chains”.

Travel and Tourism

Businesses in the travel and tourism industry (e.g. hotels, restaurants and tour companies) may be linked to the risks of child labour and has significant risks of facilitating child trafficking, particularly in the aviation industry.

Travel and tourism-specific risk factors include the following:

- Developing countries: Children in developing countries are often put to work selling tourist gifts or supporting family businesses like restaurants. Although this type of work is acceptable for children — provided that it is not hazardous and does not prevent them from receiving an education — it may also constitute child labour if it does preclude children’s school attendance.

- Child sexual exploitation: Child sex tourism does exist, and the trafficking or use of children for sexual activities for tourists occurs around the world.

Businesses in other sectors that use travel and tourism services as part of their business activities or in their supply chains may also be linked to child exploitation.

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Guidelines on Decent Work and Socially Responsible Tourism: These guidelinesprovide practical information for developing and implementing policies and programmes to promote sustainable tourism and strengthen labour protection, including the protection of children from exploitation.

- ChildSafe Movement and G Adventures Inc, Child Welfare and the Travel Industry: Global Good Practice Guidelines: These guidelinesprovide information on child welfare issues throughout the travel industry, as well as guidance for businesses on preventing all forms of exploitation and abuse of children that could be related to the tourism industry.

- International Tourism Partnership, The Know How Guide: Human Rights and the Hotel Industry: This guide provides an overview of human rights (including child labour) within hospitality, with guidance on developing a human rights policy, performing due diligence and addressing any adverse human rights impacts.

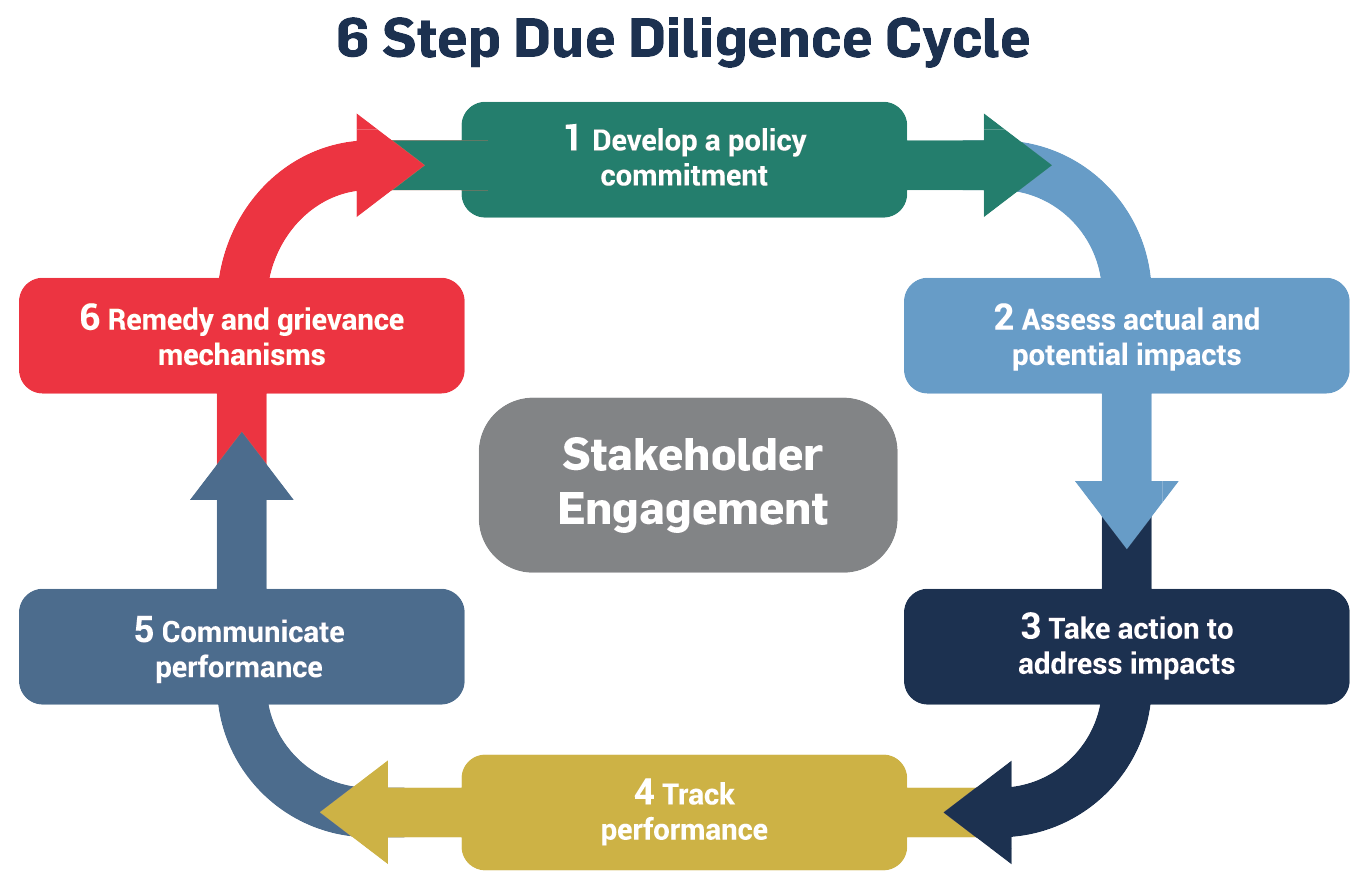

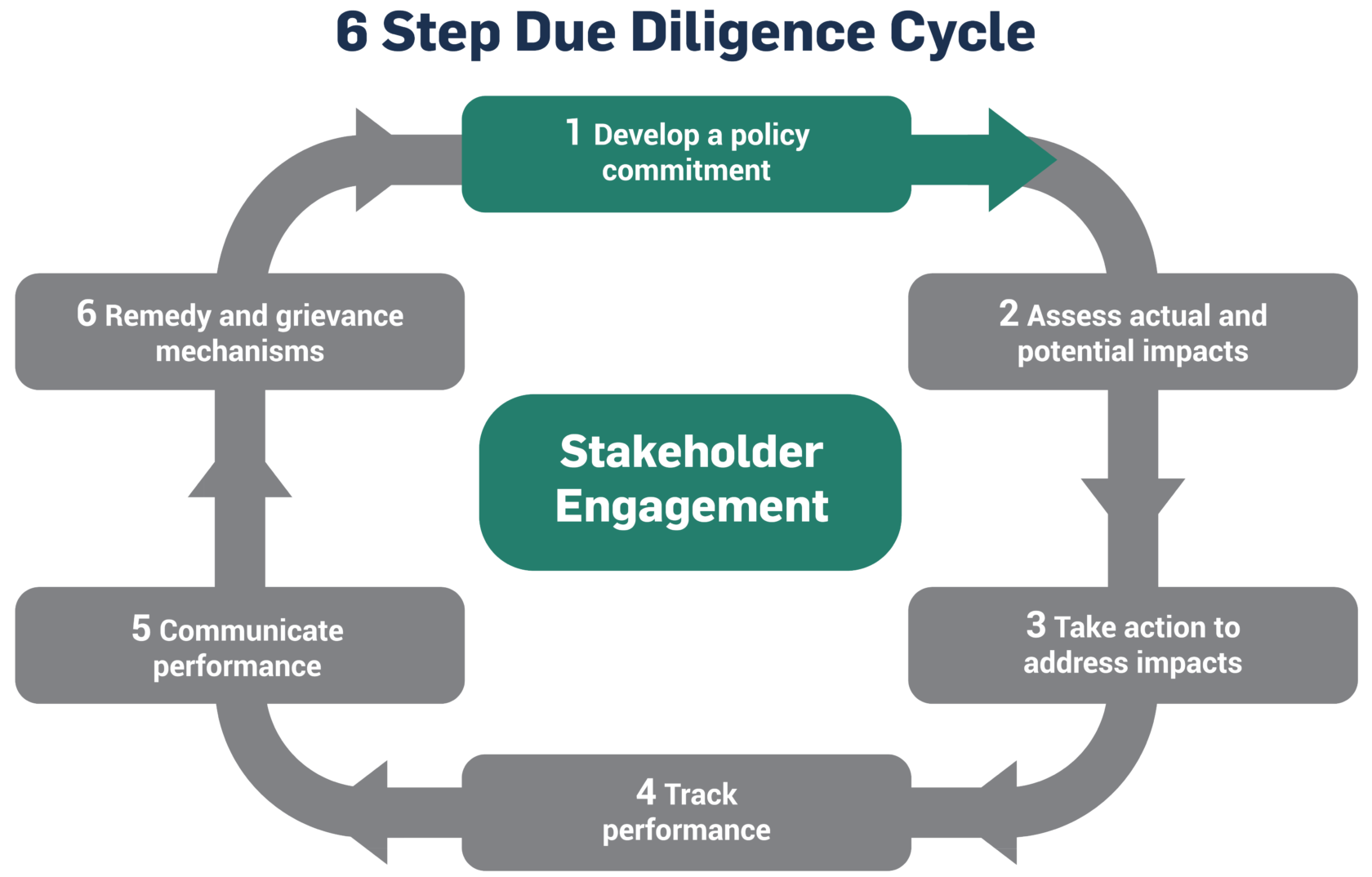

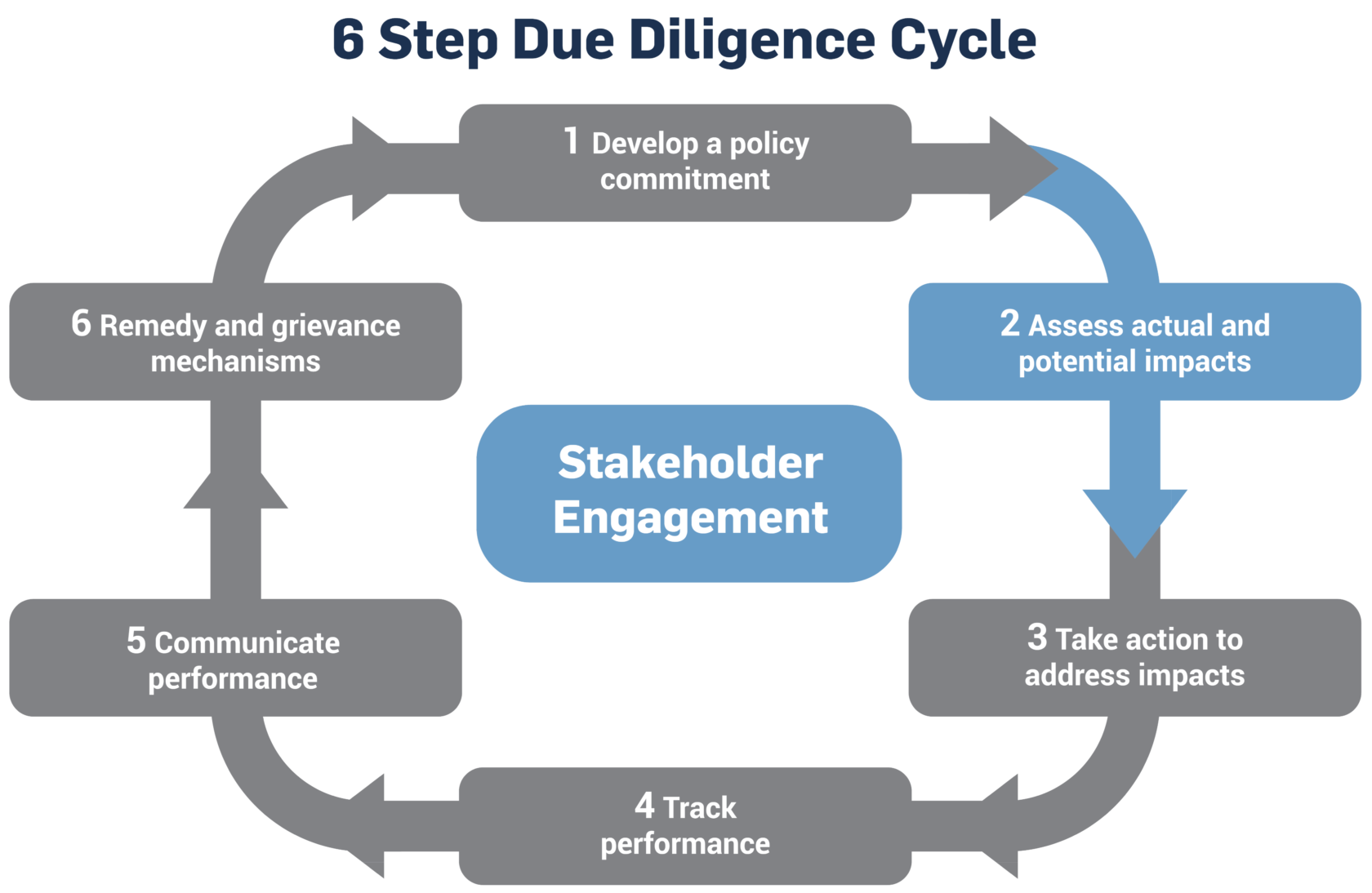

Due Diligence Considerations

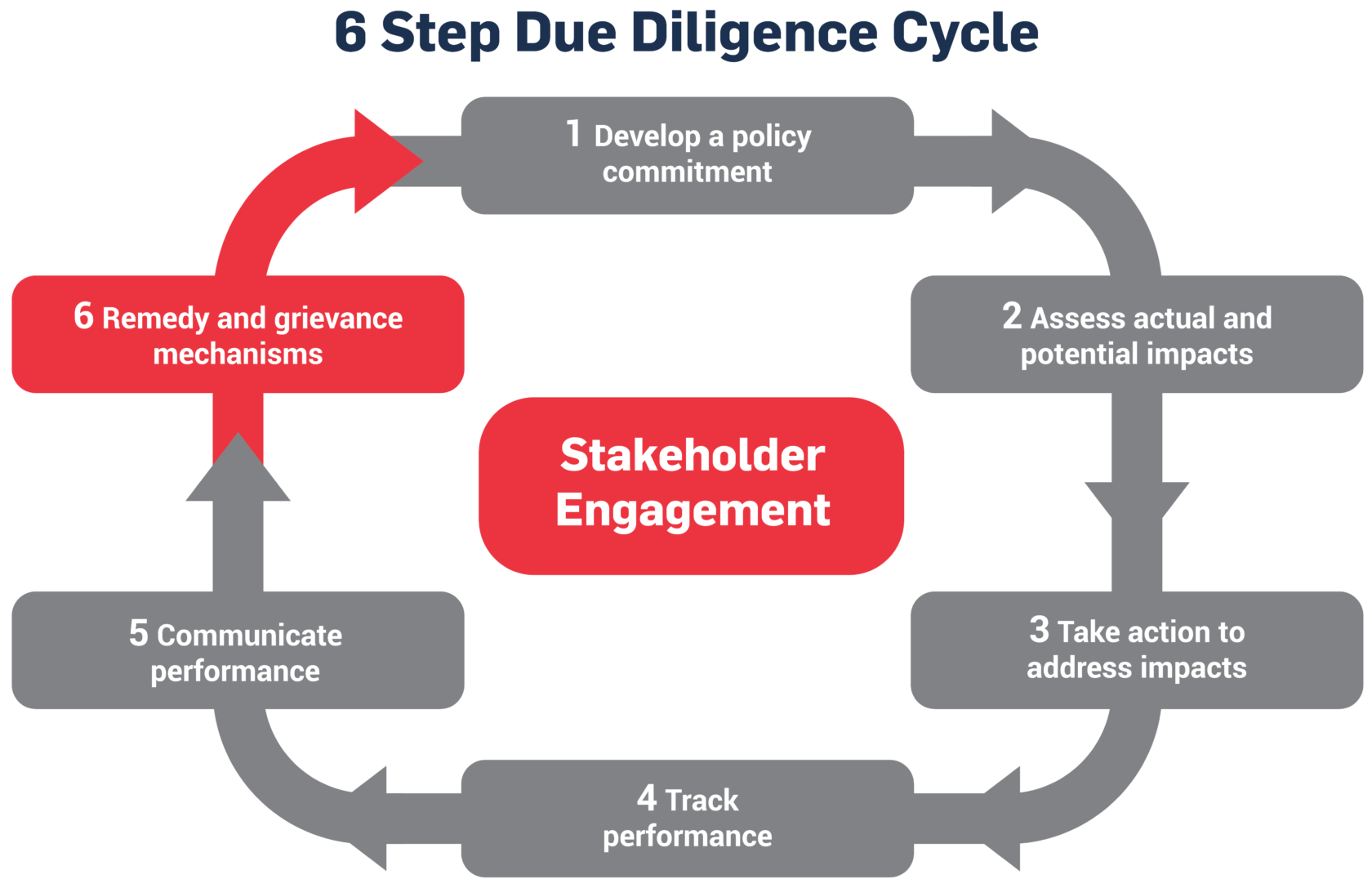

This section outlines due diligence steps that companies can take to eliminate child labour in their operations and supply chains. The described due diligence steps are aligned with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). Further information on UNGPs is provided in the ‘Key Human Rights Due Diligence Frameworks’ section below or in the Introduction.

While the below steps provide guidance on eliminating child labour in particular, it is generally more resource-efficient for companies to ‘streamline’ their human rights due diligence processes by also identifying and addressing other relevant human rights issues (e.g. forced labour, discrimination, freedom of association) at the same time.

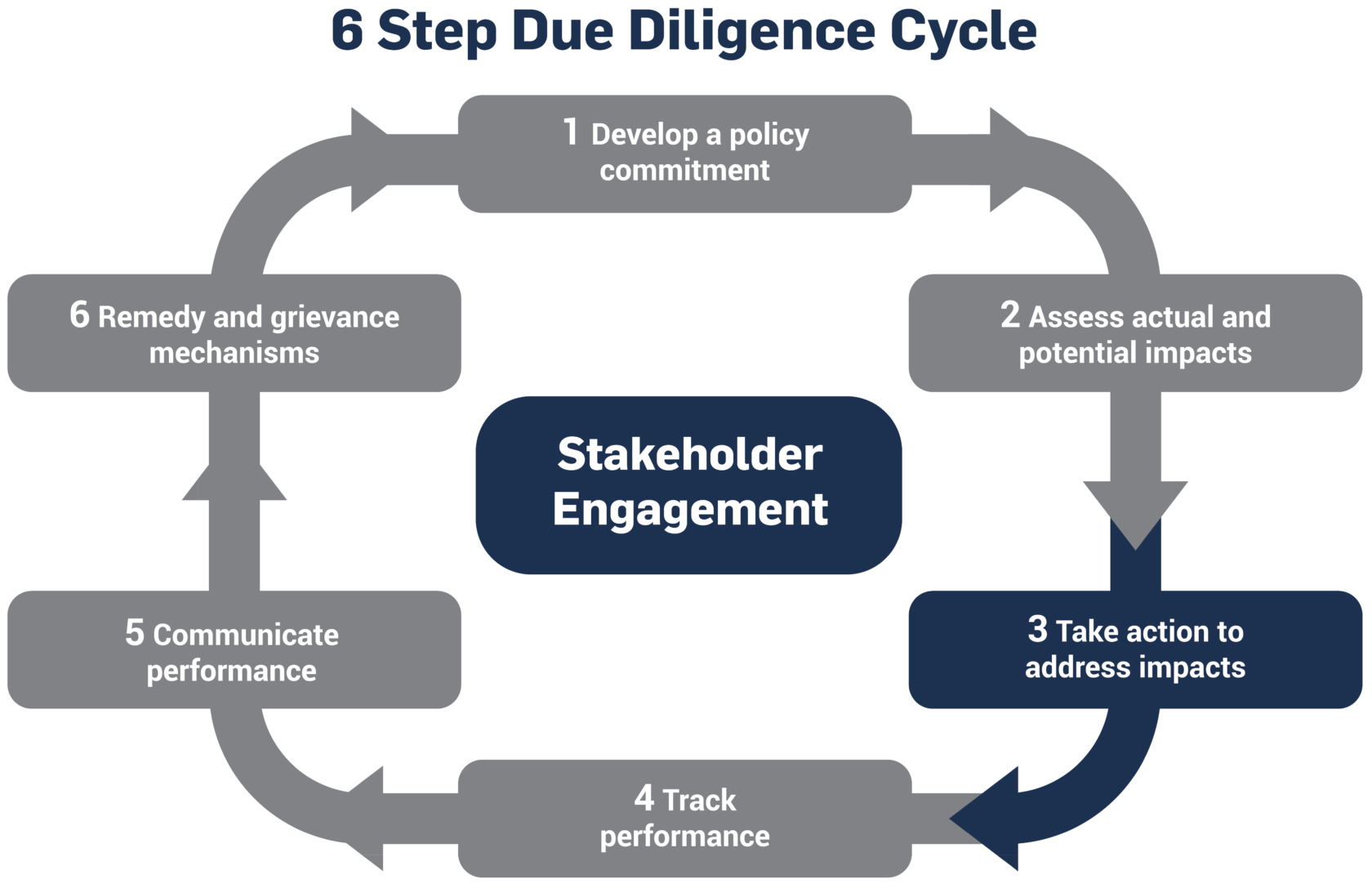

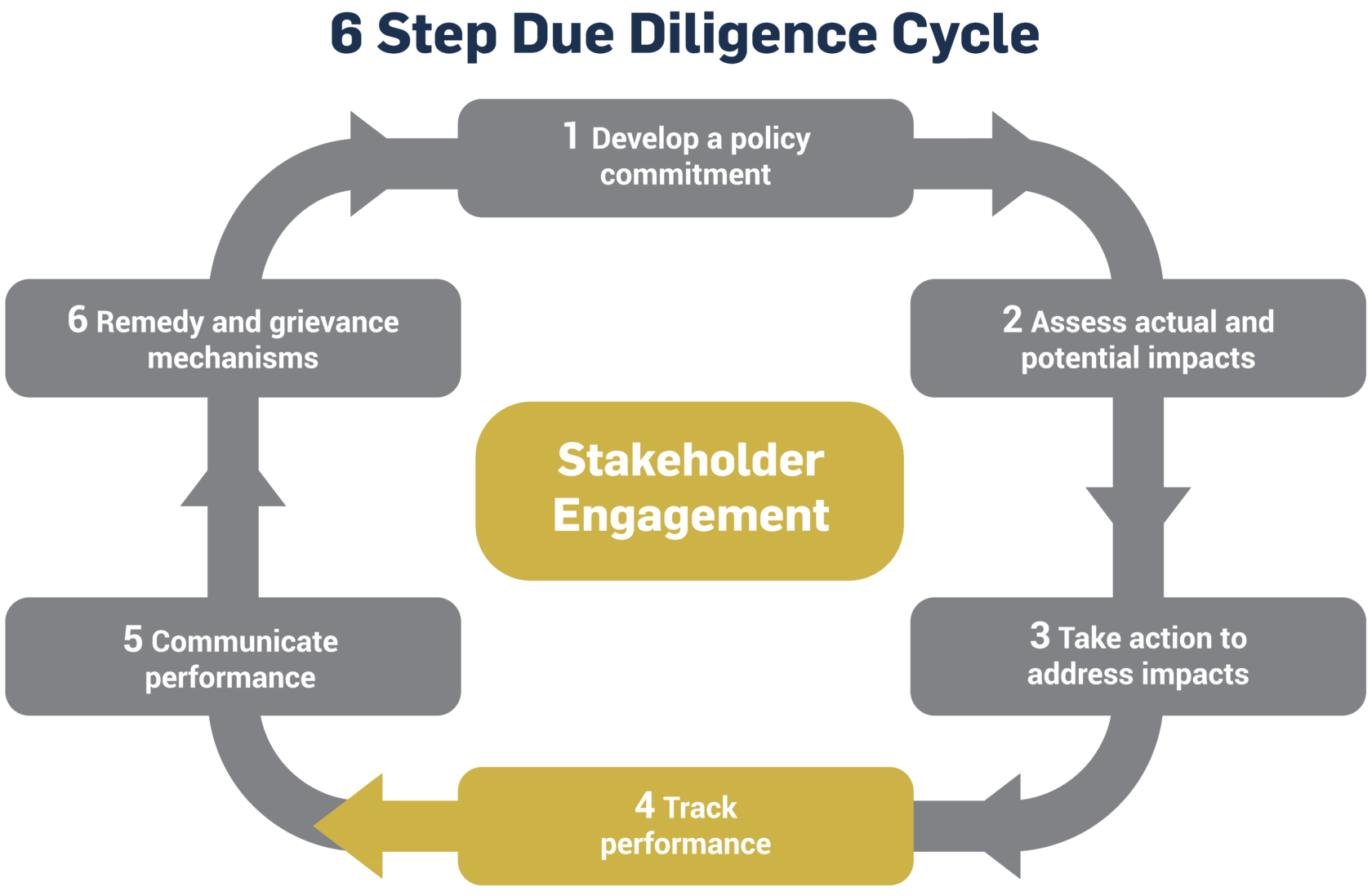

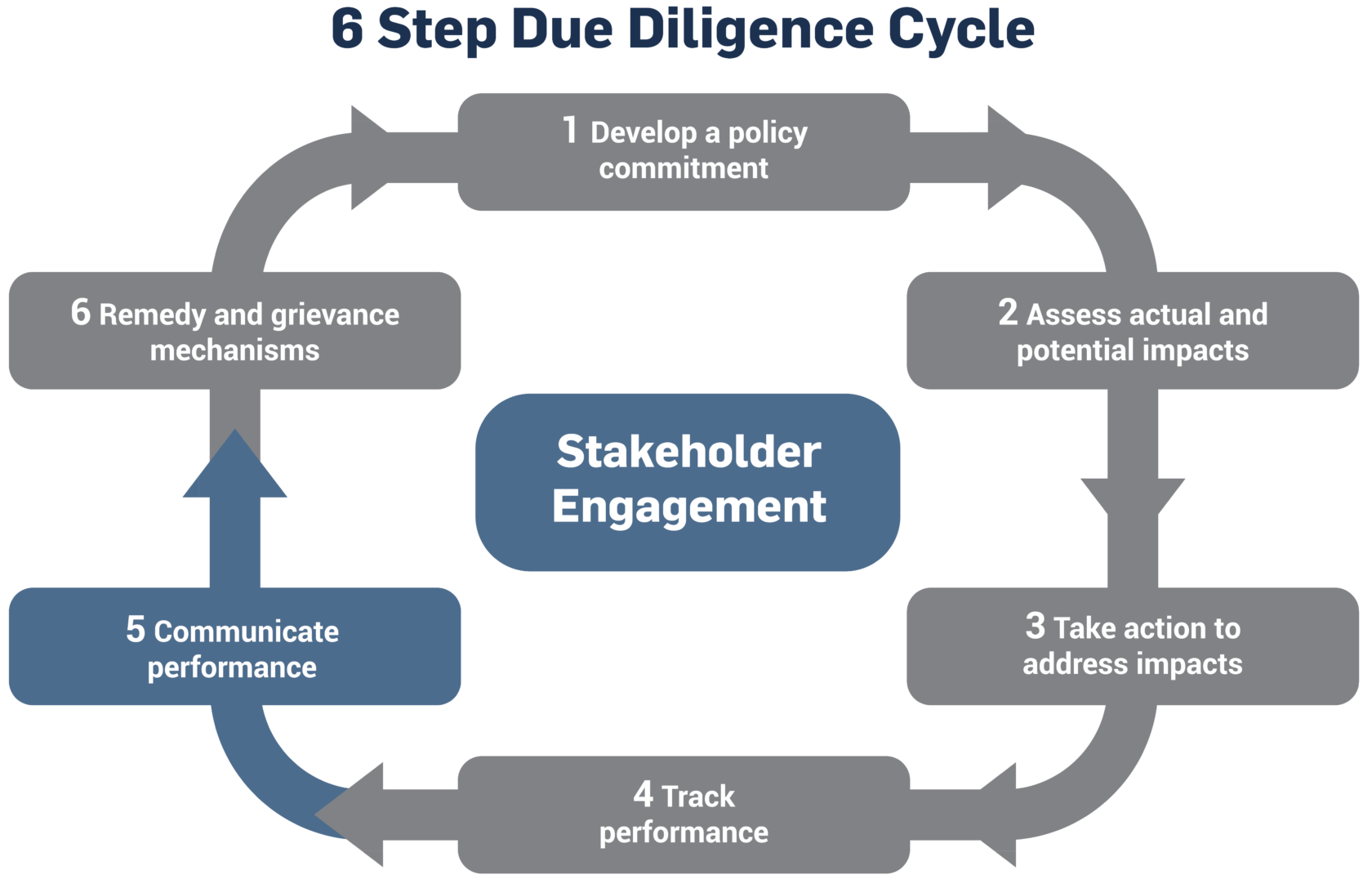

Key Human Rights Due Diligence Frameworks

Several human rights frameworks describe the due diligence steps that businesses should ideally implement to address human rights issues, including forced labour. The primary framework is the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). Launched in 2011, the UNGPs offer guidance on how to implement the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework, which establishes the respective responsibilities of Governments and businesses — and where they intersect.

The UNGPs set out how companies, in meeting their responsibility to respect human rights, should put in place due diligence and other related policies and process, which include:

- A publicly available policy setting out the company’s commitment to respect human rights;

- Assessment of any actual or potential adverse human rights impacts with which the company may be involved across its entire value chain;

- Integration of the findings from their impact assessments into relevant internal functions/processes — and the taking of effective action to manage the same;

- Tracking of the effectiveness of the company’s management actions;

- Reporting on how the company is addressing its actual or potential adverse impacts; and

- Remediation of adverse impacts that the company has caused or contributed to.

The steps outlined below follow the UNGPs framework and can be considered a process which a business looking to start implementing human rights due diligence processes can follow.

Additionally, the Children’s Rights and Business Principles (CRBPs) were based on the UNGPs as the first comprehensive set of principles to guide companies on the due diligence steps they can take to respect children’s rights in the workplace, marketplace and community.

The OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises further define the elements of responsible business conduct, including human and labour rights.

Another important reference document is the ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy (MNE Declaration), which contains the most detailed guidance on due diligence as it pertains to labour rights. These instruments, articulating principles of responsible business conduct, draw on international standards enjoying widespread consensus.

Companies can seek specific guidance on this and other issues relating to international labour standards from the ILO Helpdesk for Business. The ILO Helpdesk assists company managers and workers who want to align their policies and practices with principles of international labour standards and build good industrial relations. It has a specific section on forced labour.

Additionally, the SME Compass offers guidance on the overall human rights due diligence process by taking businesses through five key due diligence phases. The SME Compass has been developed in particular to address the needs of SMEs but is freely available and can be used by other companies as well. The tool, available in English and German, is a joint project by the German Government’s Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

1. Develop a Policy Commitment to Help Eliminate Child Labour

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, a human rights policy should be:

- “Approved at the most senior level” of the company;

- “Informed by relevant internal and/or external expertise”;

- Specific about company’s “human rights expectations of personnel, business partners and other parties directly linked to its operations, products or services”;

- “Publicly available and communicated internally and externally to all personnel, business partners and other relevant parties”; and

- “Reflected in operational policies and procedures necessary to embed it throughout the business”.

Research of 2,500 companies across nine industries conducted by the Global Child Forum suggests that 57% of companies have some form of stand-alone policy against child labour. Examples of companies with stand-alone child labour policies include ALDI South, H&M and ASOS. These tend to be companies that have identified child labour as a highly salient issue.

Another option is to integrate child labour commitments into companies’ wider human rights policy, an option that has been taken by Unilever, Marks and Spencer and Freeport-McMoRan. Where companies do not have a human rights policy, child labour is often addressed in other policy documents, such as a business code of conduct or ethics and/or a supplier code of conduct. Starbucks, BHP and HP offer examples of multinational companies that integrate child labour requirements into their codes of conduct. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs), such as Haas & Co. Magnettechnik GmbH, also often include child labour in their business code of conduct or supplier code of conduct.

Businesses may want to check the ILO Helpdesk for Business, which provides answers to the most common questions that businesses may encounter while developing their child labour policies — or integrating child labour commitments into other policy documents. Examples include:

- I am trying to figure out why the basic minimum age is set at 15 or 14. What would be the consequences of setting a global policy with a basic minimum age at 16?

- A company is committed to not recruiting people below 18 years old, but the company operates in States where people below 18 have the right to work. Can it be considered as a breach of ILO Conventions related to discrimination?

- What are the general recommendations concerning apprenticeships to use when clarifying our child labour requirements to our suppliers?

Businesses may also consider aligning their policies with relevant industry-wide or cross-industry policy commitments, for example:

- Responsible Business Alliance (RBA) Code of Conduct

- Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI) Base Code

- amfori BSCI Code of Conduct

- Fair Labor Association (FLA) Code of Conduct

- The Code of Conduct for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation in Travel and Tourism initiated by ECPAT, the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and several tour operators

Helpful Resources

- ILO, Helpdesk for Business on International Labour Standards: The ILO Helpdesk for Businessis a resource for company managers and workers on how to better align business operations with international labour standards, including child labour.

- ILO-IOE, Child Labour Guidance Tool for Businesses: This guidanceincludes several diagnostic questions that businesses could ask to evaluate their child labour policy.

- ILO, Child Labour Platform: Good Practice Notes: Guidanceon developing children’s rights and labour policies with examples from business.

- UNICEF and Save the Children, Children’s Rights in Policies and Codes of Conduct: This toolrecommends ways for businesses to incorporate children’s rights into their policies and codes of conduct, based on the Children’s Rights and Business Principles.

- Global Child Forum, Child Labour Policy: A Child-Centred Approach: This report gives guidanceon developing child labour policies and integrating child labour approaches into existing policies.

- United Nations Global Compact-OHCHR, A Guide for Business: How to Develop a Human Rights Policy: This guidanceprovides recommendations on how to develop a human rights policy and includes extracts from companies’ policies referencing child labour.

- SME Compass: Provides adviceon how to develop a human rights strategy and formulate a policy statement.

- SME Compass, Policy statement: Companies can use this practical guide to learn to develop a policy statement step-by-step. Several use cases illustrate how to implement the requirements.

- UN Global Compact Labour Principles, Advancing decent work in business Learning Plan: This learning plan, developed by the UN Global Compact and the International Labour Organization, helps companies understand each Labour Principle and its related concepts and best practices as well as practical steps to help companies understand and take action across a variety of issues.

2. Assess Actual and Potential Child Labour Impacts

UNGP Requirements

The UNGPs note that impact assessments:

- Will vary in complexity depending on “the size of the business enterprise, the risk of severe human rights impacts, and the nature and context of its operations”;

- Should cover impacts that the company may “cause or contribute to through its own activities, or which may be directly linked to its operations, products or services by its business relationships”;

- Should involve “meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups and other relevant stakeholders” in addition to other sources of information such as audits; and

- Should be ongoing.

Impact assessments should look at both actual and potential impacts, i.e. impacts that have already manifested or could manifest. This contrasts to a risk assessment that would only look at potential impacts and may not satisfy all of the above criteria.

Child labour impact assessments are most often integrated into broader human rights impact assessments (for example Freeport-McMoRan). The ILO-IOE Child Labour Guidance Tool for Businesses includes suggestions on how to identify and assess actual and potential child labour impacts; how to prioritize operations and parts of a supply chain to conduct more detailed assessments; and how to conduct stakeholder engagement. If impact assessments involve children through interviews or other data gathering mechanisms, strict safeguarding measures should be put in place to protect the children from any potential harm, such as employer retaliation or unplanned termination of employment.

Helpful Resources

- ILO and IOE, Child Labour Guidance Tool for Business: Helpful guidanceon how businesses can systematically identify and assess actual or potential child labour impacts.

- UNICEF and the Danish Institute for Human Rights, Children’s Rights in Impact Assessments: A Guide for Integrating Children’s Rights into Impact Assessments and Taking Action for Children: This guidegives specific advice on how to conduct a child-sensitive impact assessment.

- Rainforest Alliance,Child Labor Toolkit Module 3: Risk Assessment: This toolkit provides step-by-step guidance on how to conduct a basic and in-depth risk assessment on child labour.

- UNICEF and the Global Child Forum, Children’s Rights and Business Atlas: The Atlasprovides quantitative scores on risks of child labour for businesses in 198 countries.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Base Code Guidance: Child Labour: A detailed guidefor businesses on assessing the actual and potential risk of child labour in global supply chains.

- US Department of Labor, List of Goods Produced by Child Labour or Forced Labordetails child labour risks in various goods and commodities, which can be used as qualitative data in risk and impact assessments.

- Human Rights Watch has a range of resourceson child labour, which could also be used as qualitative data in risk and impact assessments.

- CSR Risk Check: A toolallowing companies to check which international CSR risks (including related to child labour) businesses are exposed to and what can be done to manage them. The tool provides tailor-made information on the local human rights situation as well as environmental, social and governance issues. It allows users to filter by product/raw material and country of origin. The tool was developed by MVO Netherland; the German version is funded and implemented by the German Government’s Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights and UPJ.

3. Integrate and Take Action to Address Child Labour Impacts

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, effective integration requires that:

- “Responsibility for addressing [human rights] impacts is assigned to the appropriate level and function within the business enterprise” (e.g. senior leadership, executive and board level);

- “Internal decision-making, budget allocations and oversight processes enable effective responses to such impacts”.

The actions and systems that a company will need to apply will vary depending on the outcomes of its impact assessment. Any actions should take into account (and try to address) risk factors and root causes of child labour, i.e. what caused or might cause a human rights violation.

One of the most common actions undertaken by companies is training of company employees and suppliers, which may cover child labour laws, company policies, procedures to ascertaining the age of workers and detect falsified documentation, and safety and health procedures for young workers (which often differ from those required for adults). Training can be delivered in a range of formats, such as online videos, e-learnings, in-person sessions or supplier round tables. Coca-Cola, for example, conducts training on human rights (including child labour) for employees, bottlers, suppliers and auditors. Another example is PepsiCo that conducts training for suppliers on PepsiCo’s Supplier Code of Conduct, which includes the prohibition of child labour. Businesses, however, should be mindful that training alone will not solve the problem, for example, if parents have no other option than to bring their children to work (be it for economic reasons or for lack of access to education etc.). Hence, the need to address root causes of child labour.

The ILO-IOE Child Labour Guidance Tool for Businesses includes further suggestions of practical approaches by companies to prevent or mitigate child labour in their operations and supply chains, including:

- Proactively communicating their short and medium-term needs to suppliers and other business partners so that they can plan ahead appropriately;

- Enhancing alignment and collaboration between the purchasing team and sustainability or responsible sourcing experts inside the buying company;

- Moving to integrate the two functions, making purchasing managers directly responsible for social compliance in relation to the suppliers they buy from;

- Participating in multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) whose code requires members to evaluate the role that purchasing practices can play in incentivizing negative impacts by suppliers.

Ferrero and Olam International are examples of companies taking action on child labour in cocoa supply chains through their membership in the International Cocoa Initiative (ICI). Hilton and TUI Group work on protecting children from commercial sexual exploitation — one of the worst forms of child labour — through their membership in The Code initiative.

Helpful Resources

- ILO and IOE, Child Labour Guidance Tool for Business: Helpful guidanceon integrating and taking action on child labour.

- ILO, Supplier Guidance on Preventing, Identifying and Addressing Child Labour: A practicalguidance for factories and other production sites on effective age verification and measures to protect young workers.

- ILO, Child Labour Platform: Good Practice Notes: Provides guidanceon embedding child-centred practices and management systems within a business.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Base Code Guidance: Child Labour: A detailed guideon actions that businesses can take to eliminate child labour in global supply chains.

- Global Child Forum, Child Labour Policy: A Child-Centred Approach: Guidanceon embedding child labour policies in practice.

- SME Compass: Provides adviceon how to take action on human rights by embedding them in your company, creating and implementing an action plan, and conducting a supplier review and capacity building.

- SME Compass, Identifying stakeholders and cooperation partners: This practical guide is intended to help companies identify and classify relevant stakeholders and cooperation partners

- SME Compass, Standards Compass: This online tool offers guidance on what to pay attention to when selecting sustainability standards or when participating in multi-stakeholder initiatives. It allows comparing standards and initiatives with respect to their contribution to human rights due diligence and their potential limitations.

- UNICEF, Engaging Stakeholder’s on Children’s Rights: This tool offers guidance to companies on how to engage stakeholders on children’s rights to help enhance their standards and practices at both the corporate and site levels.

4. Track Performance on Eliminating Child Labour

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, tracking should:

- “Be based on appropriate qualitative and quantitative indicators”;

- “Draw on feedback from both internal and external sources, including affected stakeholders” (e.g. through grievance mechanisms).

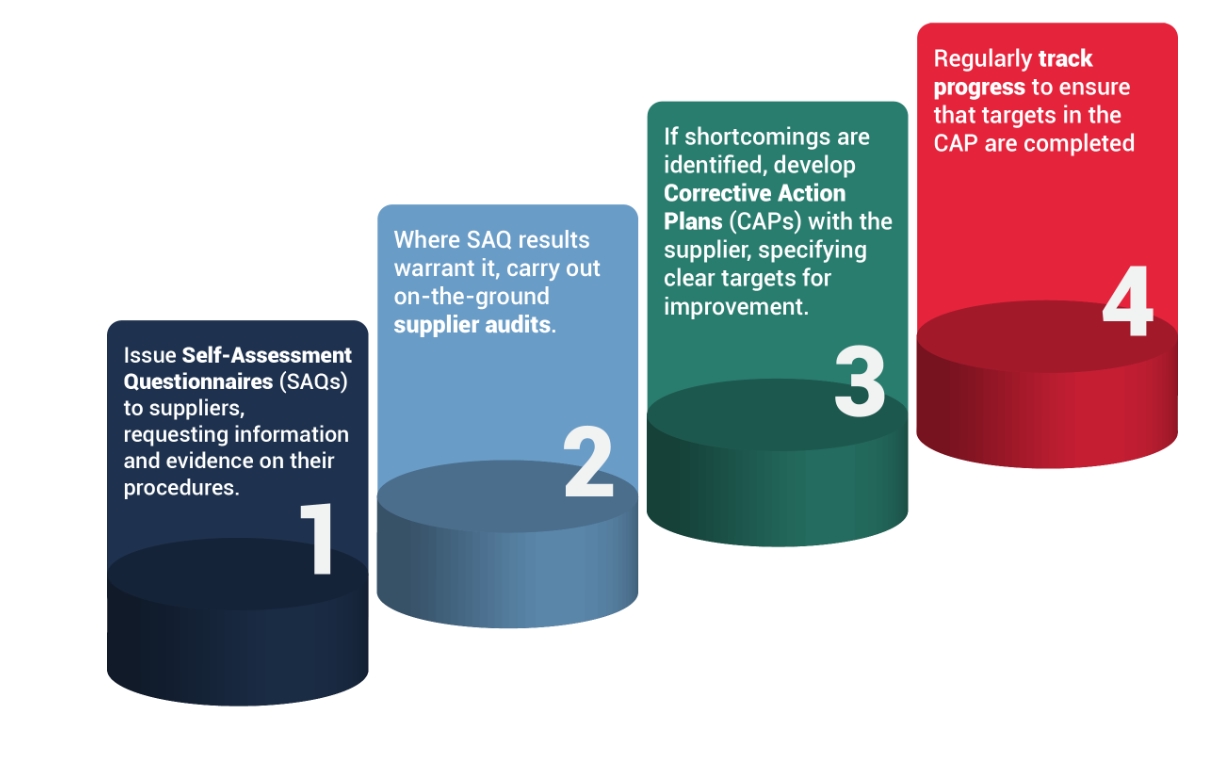

Businesses should regularly review their approach to eliminating child labour to see if it is effective and is having the desired impact. The ILO-IOE Child Labour Guidance Tool for Businesses includes suggestions on systems for tracking performance.

Audits and social monitoring are common ways to check performance. Such monitoring or audits can be undertaken internally by the company or a third party contracted by the company. A common approach or first step taken by companies is to issue self-assessment questionnaires (SAQs) to suppliers, requesting information and evidence on their child labour procedures, such as how they verify the age of their workers or their own approach to managing child labour. Repeated SAQs can give insight into improvements in supplier management systems and let suppliers self-report on actual or potential child labour impacts.

Where SAQ results warrant it, companies can carry out on-the-ground (or in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic) remote suppliers audits. Common supplier audit frameworks that span most industries and include child labour indicators include SMETA audits and SA8000 accredited audits. General Mills, for example, conducts SMETA audits of its suppliers and co-packers.

If shortcomings are identified, Corrective Action Plans (CAPs) should be developed jointly with the supplier, setting out clear targets and milestones for improvement. Progress should then be tracked regularly to ensure CAP completion.

Setting SMART targets helps objectively track performance. SMART targets are those that are: specific, measurable, attainable, resourced and time-bound. Examples of indicators to be recorded and monitored include:

- Child labour grievances recorded (number and nature)

- Audit findings on child labour

- Progress on Corrective Action Plans

- Media reports on instances of child labour

- Official inspection outcomes

Responsibility for data collection should be clearly allocated to relevant roles within the company and reported with a set frequency (for instance once a month).

Although both SAQs and audits are commonly used by companies in various industries, both tools have limitations in their ability to uncover hidden violations, including child labour. Unannounced audits somewhat mitigate this problem but even these are not always effective at identifying violations given that an auditor tends to spend only limited time on-site. Furthermore, human rights violations, including child labour, often happen further up supply chains, whereas audits often only cover ‘Tier 1’ suppliers.

New tools such as technology-enabled worker surveys/‘worker voice’ tools allow real-time monitoring and partly remedy the problems of traditional audits. An increasing number of companies complement traditional audits with ‘worker voice’ surveys (e.g. Unilever and VF Corporation), which can be easily adapted to different languages to accommodate workers’ needs.

Some companies go further and adopt ‘beyond audit’ approaches, which are built on proactive collaboration with suppliers rather than on supplier monitoring (‘carrots’ rather than ‘sticks’). Collaborating with other stakeholders, including workers’ organizations, law enforcement authorities, labour inspectorates and non-governmental organizations to proactively identify and remediate child labour can also prove to be effective. Progress reports from MSIs, such as the Responsible Mica Initiative, may also be helpful to track improvements in areas that are highly relevant to the occurrence of child labour.

Helpful Resources

- ILO and IOE, Child Labour Guidance Tool for Business: This tool includes helpful guidance on monitoring and performance tracking.

- Global Child Forum, Child Labour Policy: A Child-Centred Approach: Outlines different approaches to tracking performance on child labour, particularly Approach 6.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Base Code Guidance: Child Labour: A step-by-step guidefor businesses on eliminating child labour in global supply chains, including Step 4 ‘Monitoring implementation and impact’.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to measure human rights performance.

- SME Compass: Key performance indicators for due diligence: Companies can use this overview of selected quantitative key performance indicators to measure implementation, manage it internally and/or report it externally.

- SME Compass: Measuring and reporting on progress: This resource provides an overview of how to measure and report on the progress of the actions taken to address human rights impacts.

5. Communicate Performance on Eliminating Child Labour

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, regular communications of performance should:

- “Be of a form and frequency that reflect an enterprise’s human rights impacts and that are accessible to its intended audiences”;

- “Provide information that is sufficient to evaluate the adequacy of an enterprise’s response to the particular human rights impact involved”; and

- “Not pose risks to affected stakeholders, personnel or to legitimate requirements of commercial confidentiality”.

Companies are expected to communicate their performance on eliminating child labour in a formal public report, which can take a form of a standalone child labour report (e.g. Nestlé’s Tackling Child Labour reports). More commonly, however, an update on progress with eliminating child labour is included in a broader sustainability or human rights report (e.g. Unilever’s Human Rights reports), or in an annual Communication on Progress (CoP) in implementing the Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact. Additionally, other forms of communication may include in-person meetings, online dialogues and consultation with affected stakeholders.

The ILO-IOE Child Labour Guidance Tool for Businesses includes detailed recommendations on the form and frequency of a company’s communications on child labour, the nature of provided information and the risks of communication to children and their families.

Helpful Resources

- ILO and IOE, Child Labour Guidance Tool for Business: This tool has helpful guidance on how to report child labour approaches and results.

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), GRI408: Child Labor 2016: GRI sets out the reporting requirements on child labour for companies to achieve standard 408.

- UNICEF, Children Are Everyone’s Business: Workbook 2.0: This workbook includes guidance on integrating children’s rights into sustainability reporting.

- UNICEF, Children’s Rights in Sustainability Reporting: A Guide for Incorporating Children’s Rights into GRI-based Reporting: A practical tool to help companies with reporting and communicating on how they are respecting and supporting children’s rights.

- UNGP Reporting Framework: A short series of smart questions (‘Reporting Framework’), implementation guidance for reporting companies, and assurance guidance for internal auditors and external assurance providers.

- United Nations Global Compact, Communication on Progress (CoP): The CoP ensures further strengthening of corporate transparency and accountability, allowing companies to better track progress, inspire leadership, foster goal-setting and provide learning opportunities across the Ten Principles and SDGs.

- The Sustainability Code: A framework for reporting on non-financial performance that includes 20 criteria, including on human rights and employee rights.

6. Remedy and Grievance Mechanisms

UNGP Requirements

As per the UNGPs, remedy and grievance mechanisms should include the following considerations:

- “Where business enterprises identify that they have caused or contributed to adverse impacts, they should provide for or cooperate in their remediation through legitimate processes”.

- “Operational-level grievance mechanisms for those potentially impacted by the business enterprise’s activities can be one effective means of enabling remediation when they meet certain core criteria.”

To ensure their effectiveness, grievance mechanisms should be:

- Legitimate: “enabling trust from the stakeholder groups for whose use they are intended, and being accountable for the fair conduct of grievance processes”

- Accessible: “being known to all stakeholder groups for whose use they are intended, and providing adequate assistance for those who may face particular barriers to access”

- Predictable: “providing a clear and known procedure with an indicative time frame for each stage, and clarity on the types of process and outcome available and means of monitoring implementation”

- Equitable: “seeking to ensure that aggrieved parties have reasonable access to sources of information, advice and expertise necessary to engage in a grievance process on fair, informed and respectful terms”

- Transparent: “keeping parties to a grievance informed about its progress, and providing sufficient information about the mechanism’s performance to build confidence in its effectiveness and meet any public interest at stake”

- Rights-compatible: “ensuring that outcomes and remedies accord with internationally recognized human rights”

- A source of continuous learning: “drawing on relevant measures to identify lessons for improving the mechanism and preventing future grievances and harms”

- Based on engagement and dialogue: “consulting the stakeholder groups for whose use they are intended on their design and performance, and focusing on dialogue as the means to address and resolve grievances”

Grievance mechanisms can play an important role in helping to remediate child labour issues in operations and supply chains. Grievance mechanisms should be:

- Created with input from the affected groups they are intended to help;

- Available in multiple formats and languages to accommodate workers’ needs. For instance, a high prevalence of migrant labour means a mechanism will need to be available in different languages, or illiteracy may require the mechanism to be explained to workers in a format other than writing (for example a video or presentation).

If instances of child labour are identified, corrective actions should be taken to protect the child from child labour and ensure that the child is not left in a worse situation due to loss of income. Ensuring viable alternatives is key. Child-focused actions can include:

- Providing education alongside work if the child is above the minimum age, but if the child is below minimum age the child should be progressively withdrawn from child labour;

- Removing the child but paying the wages they would have earned until they reach working age;

- Assisting the child in finding education opportunities once removed from work; and

- Assisting the child in finding employment opportunities upon reaching the legal working age.

Businesses may also want to consider cooperation with third parties to remediate child labour, including education officials, NGOs, public health officials and other companies using the same supply chain. In cases concerning the worst forms of child labour, this may even be a legal requirement. MSIs are also helpful in designing child labour remediation programmes, i.e. exchanging thoughts and ideas, and combining remediation efforts. Examples of companies with child labour remediation programmes include Nestlé and ASOS.

Helpful Resources

- ILO and IEO, Child Labour Guidance Tool for Business: This tool includes helpful guidance on remediation actions and grievance mechanisms for businesses.

- ILO, Child Labour Platform: Good Practice Notes (particularly sections 4 and 5): Guidance on approaches for businesses to establish and implement remedial systems and actions.

- ILO, Supplier Guidance on Preventing, Identifying and Addressing Child Labour: A practical guidance for factories and other production sites on remediating child labour.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Base Code Guidance: Child Labour: A step-by-step guide for businesses on eliminating child labour in global supply chains, including Step 3 ‘Mitigation of risk and remediation for child workers’.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Access to Remedy: Practical Guidance for Companies: This guidance explains key components of the mechanisms that allow workers to submit complaints and enable businesses to provide remedy.

- Global Compact Network Germany, Worth Listening: Understanding and Implementing Human Rights Grievance Management: A business guide intended to assist companies in designing effective human rights grievance mechanisms, including practical advice and case studies. Also available in German.

- SME Compass: Provides advice on how to establish grievance mechanisms and manage complaints.

Case Studies

This section includes examples of company actions to address child labour in their operations and supply chains.

Further Guidance

Examples of further guidance on child labour include:

- United Nations Global Compact, The Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact: The Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact provide universal guidance for sustainable business in the areas of human rights, labour, the environment and anti-corruption. Principle 5 calls on businesses to uphold the elimination of child labour.

- United Nations Global Compact, Business: It’s Time to Act: Decent Work, Modern Slavery & Child Labour: This brief guide offers an overview of the steps businesses can take to help eliminate child labour while highlighting key resources, initiatives and engagement opportunities to support business action.

- ILO, COVID-19 and Child Labour: A Time of Crisis, a Time to Act: This report outlines the impact of the global COVID-19 pandemic on child labour trends.

- ILO, Understanding the Health Impact of Children’s Work: This study brings together information from a wide variety of nationally representative household surveys in an attempt to shed additional light on the health effects of children’s work within and across less-industrialized countries and on which types of children’s work pose the greatest risk of ill-health.

- ILO, Towards the Urgent Elimination of Hazardous Child Labour: This report brings together and assesses new research on hazardous child labour and provides recommendations on prevention and protection.

- ILO, Improving the Safety and Health of Young Workers: This report provides a definition of young workers and outlines factors threatening their safety and health.

- ILO, Ending Child Labour, Forced Labour And Human Trafficking In Global Supply Chains: This report aims to help businesses develop policies and practices to prevent child labour in global supply chains.

- ILO, OECD, IOM and UNICEF, Multi-Stakeholder Initiative on Ending Child Labour, Forced Labour and Human Trafficking in Global Supply Chains: This resource provides recommendations on responsible business conduct on labour and human rights, including developing due diligence on child labour.

- ILO Helpdesk for Business, Country Information Hub: This resource can be used to inform human rights due diligence, providing specific country information on different labour rights.

- UNICEF, UN Global Compact and Save the Children, Children’s Rights and Business Principles: The Principles (particularly 2, 3 and 4) guide companies on actions they can take to prevent child labour.

- UNICEF and UN Global Compact, Children in Humanitarian Crises: What Business Can Do: A report on how business can help uphold children’s rights — including freedom from child labour — and support and promote their well-being during humanitarian crises.

- UNICEF, Tool for Investors on Integrating Children’s Rights into ESG Assessment: This tool has been designed to guide investors on integrating children’s rights into the evaluation of ESG opportunities and performance of investee companies.

- UNICEF, Mapping Child Labour Risks in Global Supply Chains: This paper provides a detailed analysis of the Apparel, Electronics and Agricultural Sectors. It was written as a background report for the Alliance 8.7 report on “Ending child labour, forced labour and human trafficking in global supply chains”.

- UNICEF, Engaging Stakeholder’s on Children’s Rights: This tool offers guidance to companies on how to engage stakeholders on children’s rights to help enhance their standards and practices at both the corporate and site levels.

- UNICEF, UN Global Compact and Save the Children, Children Introduce the Children’s Rights and Business Principles: This video features children from Panama teaching businesses about the Children’s Rights and Business Principles.

- UNICEF, Child Rights and Security Handbook: This tool provides details on how to implement the Child Rights and Security Checklist – a checklist for companies to improve the protection of children’s rights within security programs.

- Alliance 8.7, Delta 8.7 Knowledge Platform: A global knowledge platform providing resources on eradicating forced labour, modern slavery, human trafficking and child labour.

- Stop Child Labour, Handbook: 5×5 Stepping Stones for Creating Child Labour Free Zones: The stepping stones presented in this handbook are based on the stories and strategies of NGOs, unions and child labour free zone members worldwide. The handbook shows that — in spite of poverty — it is possible to get children out of work and into school.

- SME Compass, Due Diligence Compass: This online tool offers guidance on the overall human rights due diligence process by taking businesses through five key due diligence phases.

- SME Compass, Standards Compass: This online tool offers guidance on what to pay attention to when selecting sustainability standards or when participating in multi-stakeholder initiatives. It allows comparing standards and initiatives with respect to their contribution to human rights due diligence and their potential limitations.

- SME Compass, Measuring and reporting on progress: This resource provides an overview of how to measure and report on the progress of the actions taken to address human rights impacts.

- SME Compass, Downloads: Practical guides and checklists are available for download on the SME compass website to embed due diligence processes, improve supply chain management and make mechanisms more effective.